What do you associate with the term still life? Is it highly detailed, and realistic painted images of flower bouquets and tables laden with lavish bowls of fruit and game from a time past? Yes, the still life genre uses inanimate objects such as flowers, fruit and vegetables, and manufactured items to symbolically reflect on nature, wealth, exploration and mortality, however at present, the still life is a space for creative experimentation exploring issues of consumerism, beauty, power, postcolonialism and gender politics.

Artists have pushed the boundaries of the genre from painting and sculpture into the realms of photography, performance and new media. These works currently on display in ‘Still Life Now‘ at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane until 19 February, use strategies of repetition, appropriation and transformation to reflect or reject the concerns of traditional still lifes — such as the memento mori (a stoic visual reminder of the inevitability of death) and the vanitas still life (the use of elaborate spreads to highlight life’s transience) — to reconsider the genre in the current era of image production.

Michael Cook ‘Nature Morte (Blackbird)’

Nature Morte (Blackbird), from Michael Cook’s ‘Natures Mortes’ series, draws on visual strategies affiliated with the still‑life genre — particularly the memento mori, a visual reminder of the inevitability of death — to highlight the devastating impact of colonisation from an Indigenous point of view. Here, the black cockatoos symbolise the inhuman practices that were present in the Australian sugar industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The work’s title refers to ‘blackbirding’, a type of entrapment used to capture and transport South Sea Islander people to Australia as indentured labour to service the burgeoning cane fields and sugar industries. The wilted flowers mourn the cruelty of this practice, with the set of scales resembling a cross-like figure that marks the countless deaths of First Nations peoples.

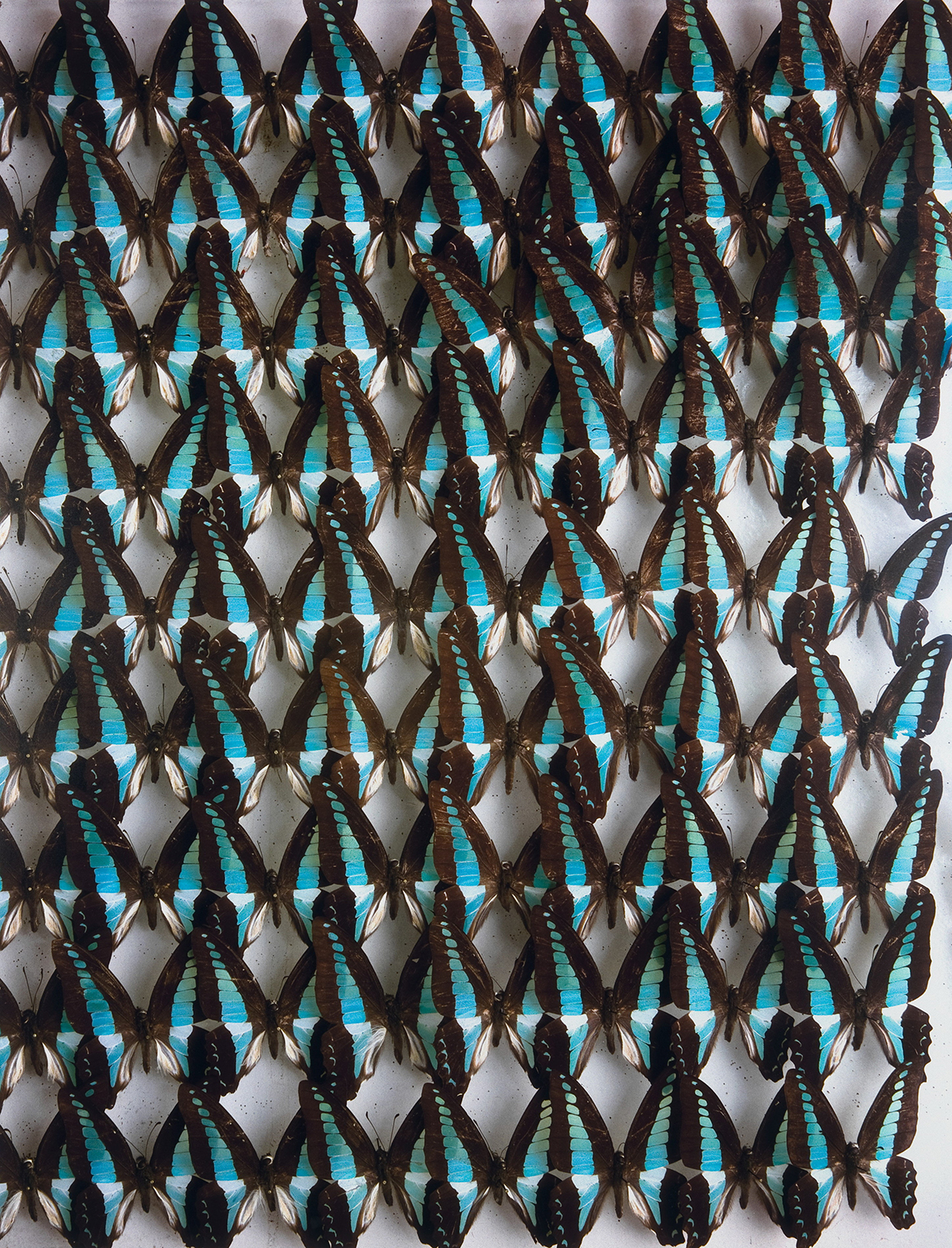

Justine Cooper ‘Blue triangle butterflies’

Moving between the beautiful and the macabre, Justine Cooper’s ‘Saved by science’ series explores the human fascination with collection and preservation. Offering a glimpse into the 32 million specimens held in the cabinets and vaults of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, Cooper draws particular attention to the multiple, demonstrating how the collected animals are assigned value en masse during the process of scientific interrogation. Unlike still lifes that draw attention to the cycle of life and the certainty of death, Cooper’s photographs demonstrate the ability of science to defy death through the superficial suspension of life.

Marian Drew ‘Possum with five birds’

The photograph Possum with five birds echoes the tone of paintings made in the still‑life tradition to explore contemporary relations to native animals killed through the expansion of urbanisation in Australia. The animals featured — destroyed either by introduced predators, land-clearing, urban development or as roadkill — are then collected by Drew and placed alongside embroidered fabrics, fine china, candles, fruits and vegetables. By positioning the animals amongst these domestic objects, the space between the human world and the animal world is reduced; emphasising the ethical responsibility that humans have to the animals that share our environments. In this still life arrangement, they remind us of the cost of urbanisation to wild animals and of humans’ ever-changing relationship with nature.

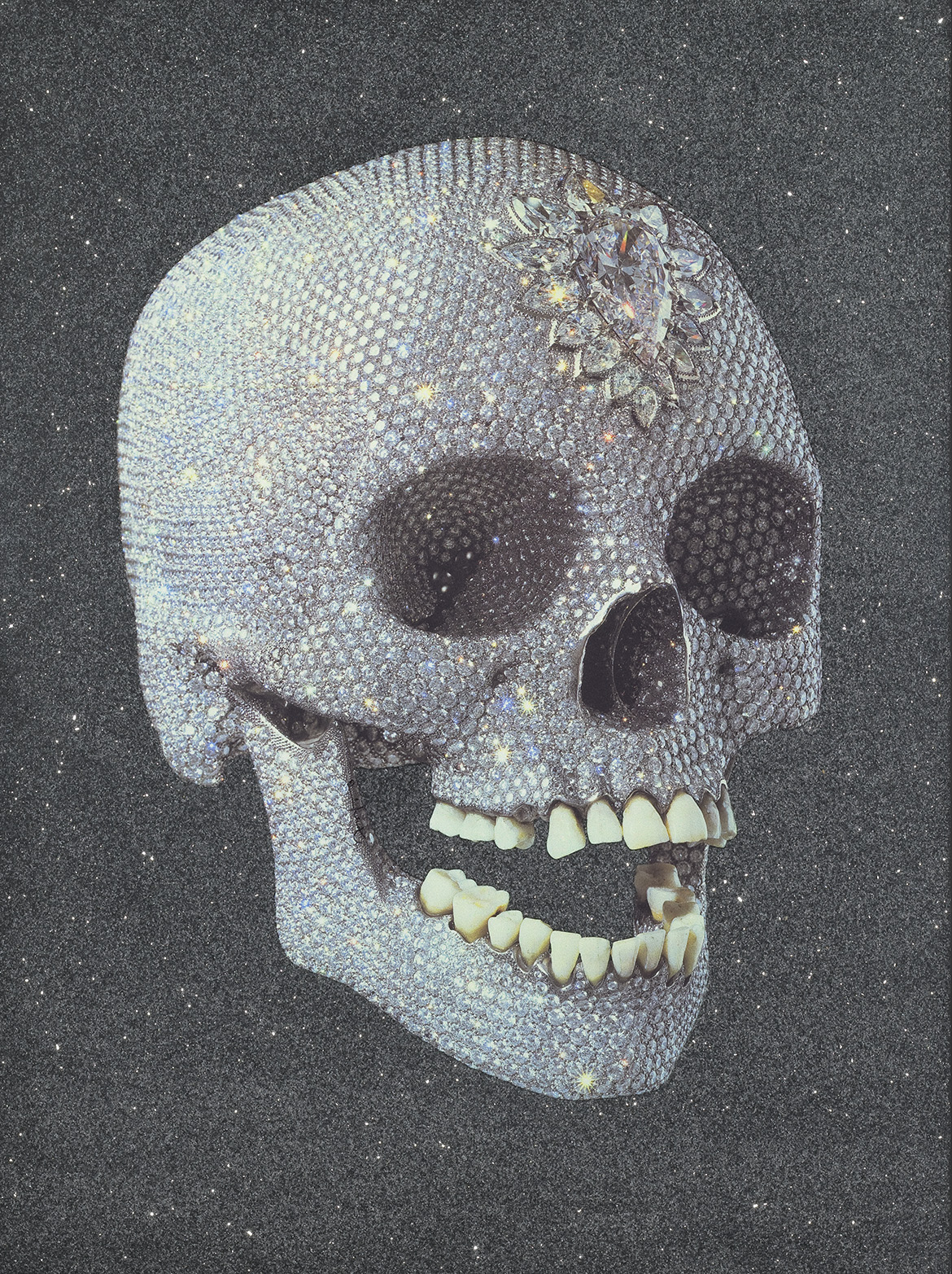

Damien Hirst ‘For the love of God, laugh’

Renowned for creating artworks that explore the dilemmas of human existence, Damien Hirst’s For the love of God, laugh rebels against mortality by transforming the human skull into a glittering object of desire. Coated with diamond dust, the print depicts Hirst’s sculptural work For the Love of God 2007, a platinum cast of an eighteenth‑century skull encrusted with 8601 diamonds. A familiar motif in memento mori still lifes, the skull is a haunting symbol of contemplation and foreboding. Our attention is drawn to its smile – the real human teeth the only part of the work not covered by diamonds – bringing a sardonic humour and sense of contempt that suggests victory over decay.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye ‘Yam dreaming’

In the ‘Yam dreaming’ series of paintings, Emily Kame Kngwarreye uses vibrant colours to trace the meandering root systems of Arlatyeye (pencil yam or bush potato) as they forge their way through the Simpson Desert. Kngwarreye’s paintings emphasise the significance of Arlateye as an essential provider of food and sustenance, as well as the subject of significant ceremonies amongst Eastern Anmatyerre people. Rather than simply observing or recording the material properties of Arlatyeye, Kngwarreye integrates her own ancestral knowledge into these paintings to create vivid compositions.

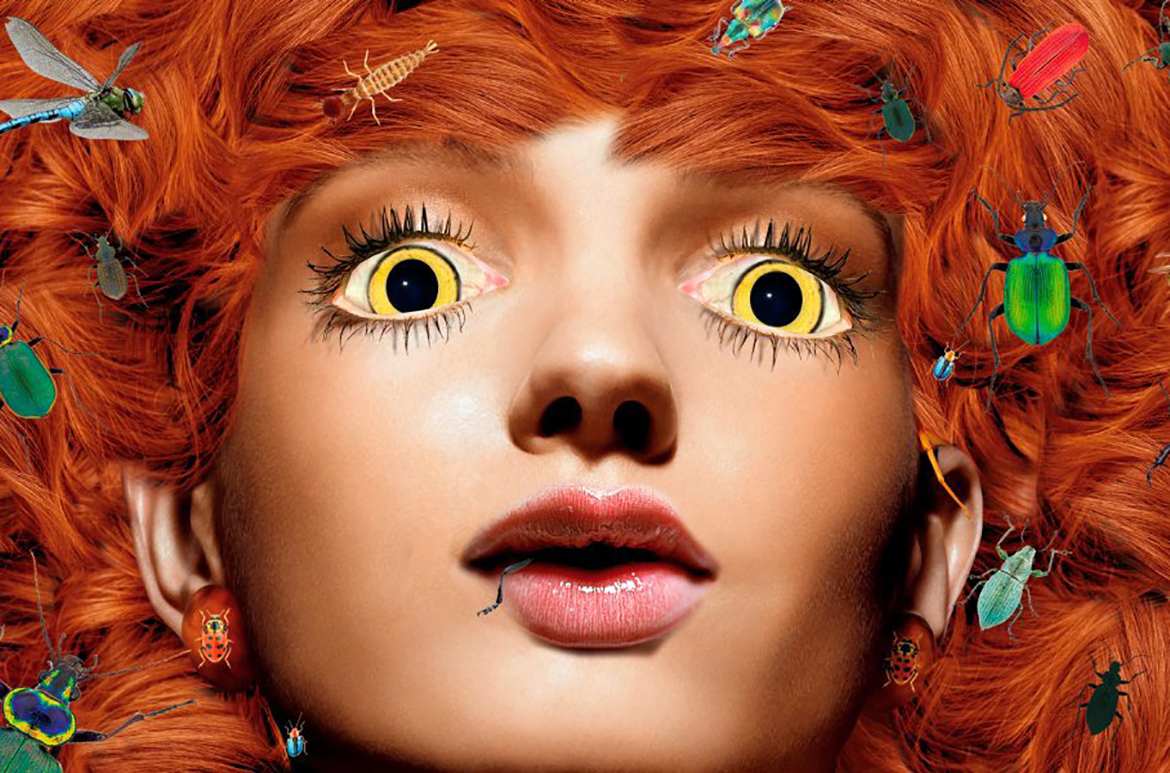

Deborah Kelly ‘Beastliness’

Deborah Kelly’s vibrant collage animation Beastliness presents a kaleidoscopic vision of the future. Featuring a cast of hybrid creatures created from the pages of obsolete encyclopaedias, textbooks and natural history magazines, Kelly uses the scaffolds of old scientific knowledge to create an alternative reality free from the constraints of heteronormativity. The work, which invokes a wild sense of sexual liberation and hedonism, also features symbolic representations of fertility and reproduction (such as nests of spinning eggs) that celebrate the corporeal magic of birth and rebirth.

Robert MacPherson ‘MAYFAIR: 4,4,JOE BIRCH’

In his paintings, Robert MacPherson often uses appropriated language and images encountered in daily life to reflect upon what constitutes a work of art. Featuring imagery and lettering taken from hand-painted road signage found on regional highways throughout Australia, MacPherson’s ‘Mayfair’ series of works uses the still life as a platform to elevate mundane road signs from a position of low to high art. Referencing pop art and the readymade, “MAYFAIR: 4,4JOE BIRCH” 1999 reveals MacPherson’s approach to the depiction of multiples — sequences of similar or identical objects – that highlight the connection of the still life to money, manufacture and trade.

Kimiyo Mishima ‘Work 21 – C4 2021’

Kimiyo Mishima skilfully recreates throwaway objects — such as newspapers, drink cans and cardboard boxes — as highly realistic hand-painted ceramics. Work 21 – C4 (C for ‘cans’) speaks to the tradition of the still life to painstakingly capture the everyday, but draws attention to the disposable nature of manmade products. In her work, Mishima uses a valuable and fragile ceramic medium to elevate the value and status of the objects and rally against wasteful overconsumption.

and iron / 74 x 56 x 56cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2021 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Kimiyo Mishima / Image courtesy: MEM, Tokyo

Anne Noble ‘Dead Bee Portrait #1’

Dead Bee Portrait #1 is from a series of photographs by Anne Noble that highlight the threat of human development on the insect world. Created from electron microscope images of dead bees, the exaggeration of the bee’s scale almost reanimates it, creating an ethereal portrait of a species on the brink of extinction. The necessary gilding of the dead bee in gold dust — to allow viewing under the microscope – reflects the still‑life tradition of using aesthetically seductive materials and ornamentation to draw attention to the fragility of life. Noble’s photographs show that the image can not only capture the physical composition of once‑living things, but also emphasises the ability of the photographic surface to offer experiences of form, time, memory and being.

Edwin Roseno ‘Aster (Novae angeliae)’

Using cans, bottles, cartons and plastic containers bought in Indonesian supermarkets, Edwin Roseno’s ‘Green hypermarket (series)’ works capture everyday objects to highlight human connections to commercial products and plant life. The photographs show a series of plants in discarded product containers, collected by Roseno from friends, neighbours and local nurseries. Although the work draws attention to environmental and economic tensions that are prevalent across the growing economies of Asia, the images are also nostalgic, alluding to the local customs lost in the face of rapid urbanisation and mass consumerism.

Victoria Wareham is Assistant Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA and Curator of ‘Still Life Now’.

‘Still Life Now’ / Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) / 24 September 2022 until 19 February 2023

#QAGOMA