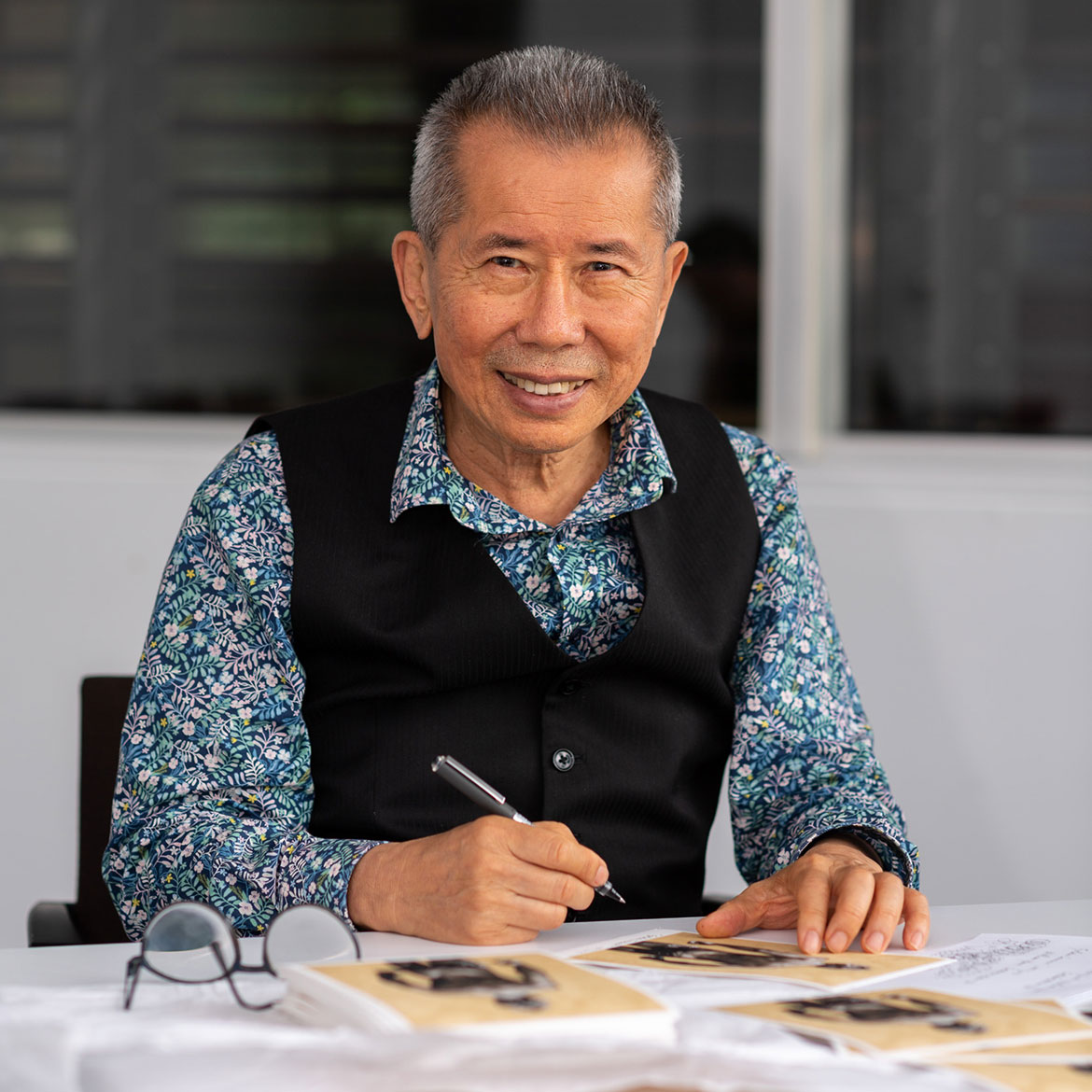

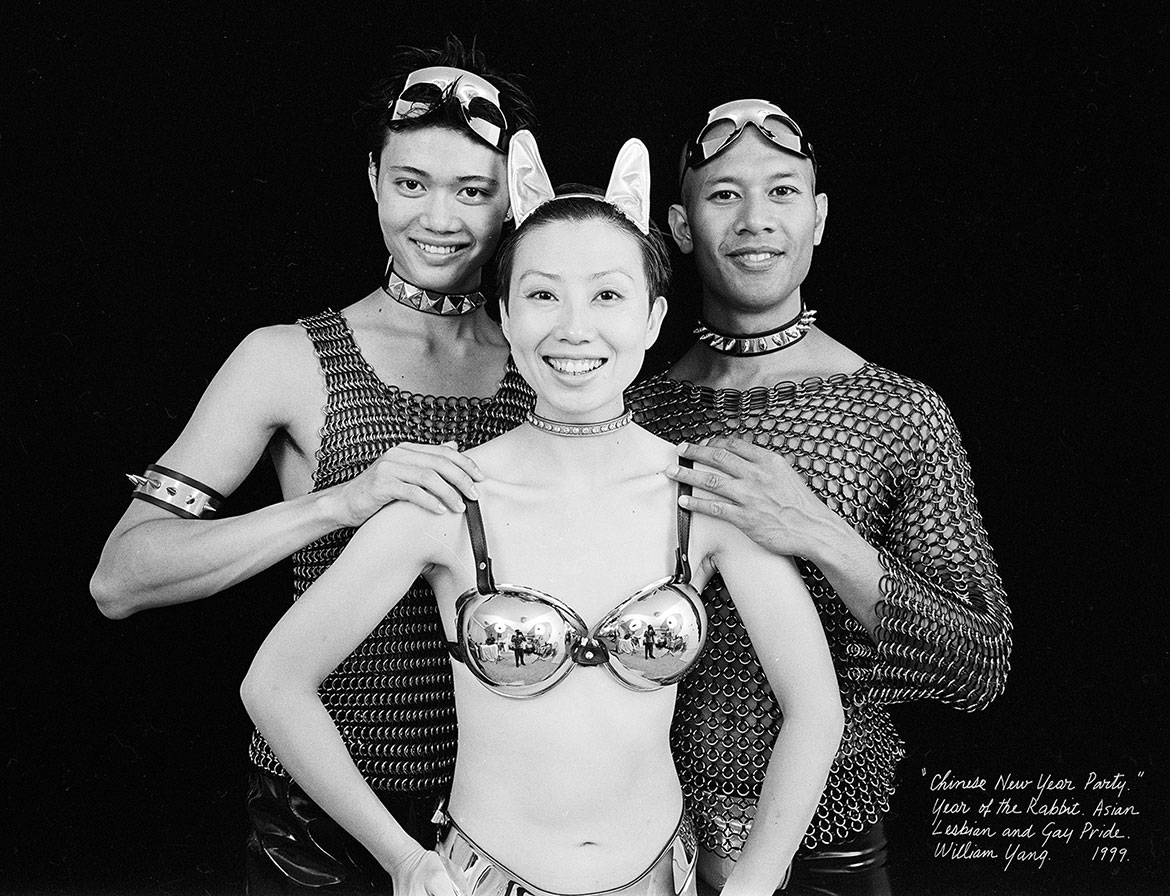

Known for his reflective and joyous depictions of Australia’s LGBTIQ+ scene in the late 1970s and 80s through to the present, Queensland-born, Sydney-based artist William Yang’s work is the subject of a major survey exhibition ‘Seeing and Being Seen’. This exhibition traces Yang’s career from documentary photography through to explorations of cultural and sexual identities and his depictions of landscape —integrating his photographic practice with writing, video and performance.

Australian beach culture

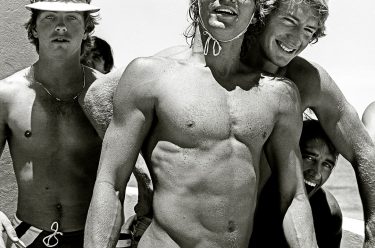

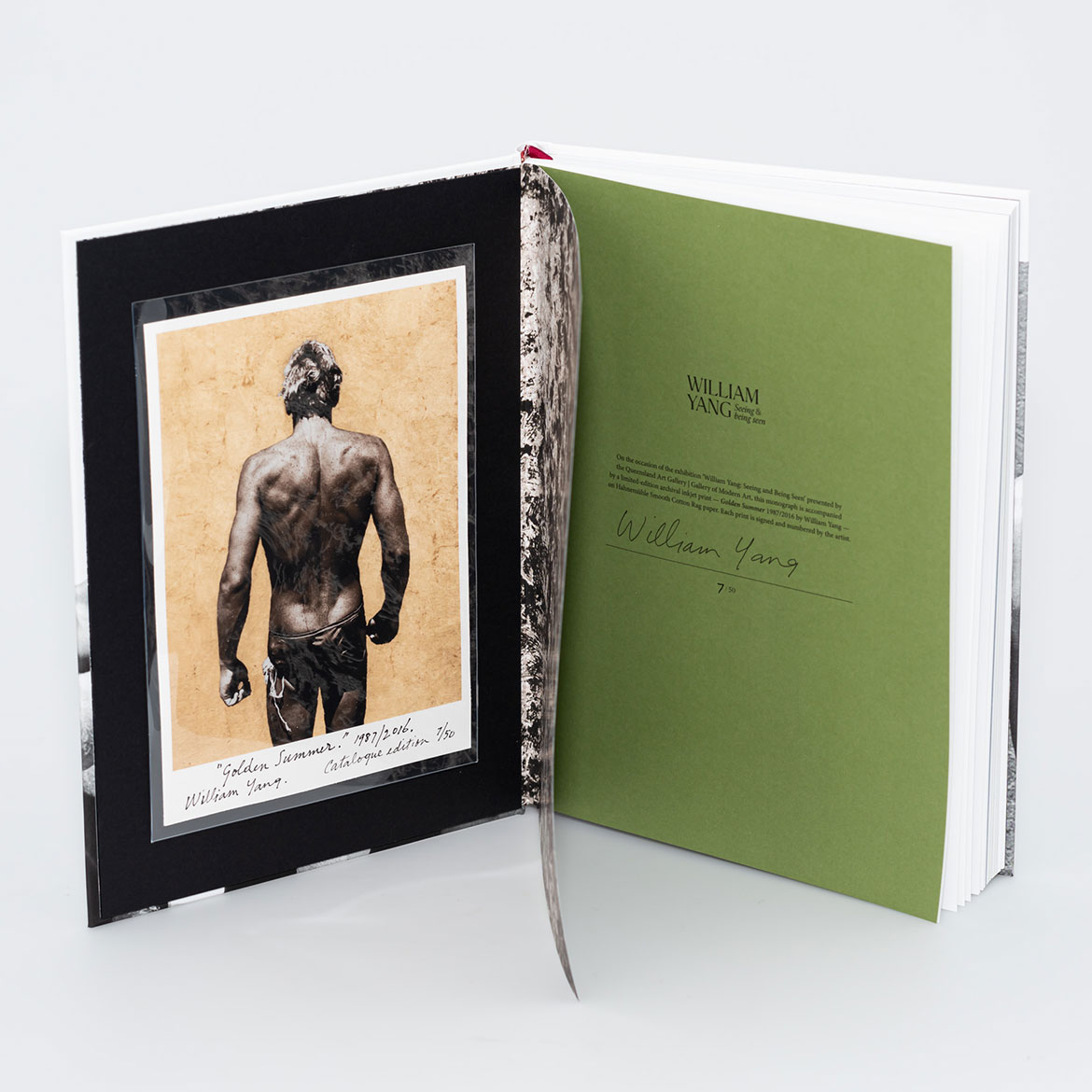

William Yang ‘Golden Summer’ 1987/2016

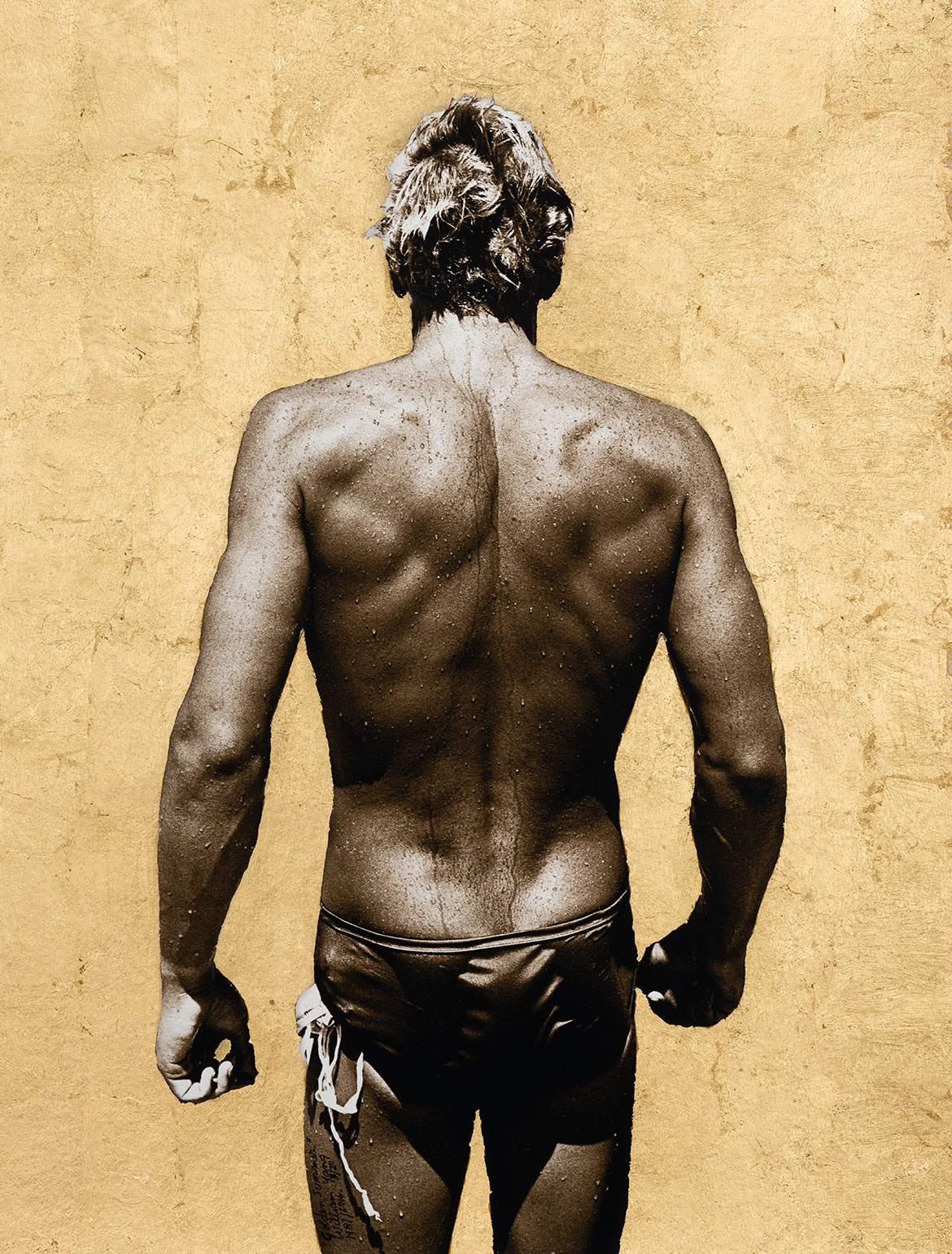

William Yang ‘Tamarama Lifesavers’ 1981

William Yang embraced the bleached allure of Sydney’s eastern beaches and took many iconic photographs of Bondi, Tamarama and Clovelly. These works combine his love of people with the landscape, and many of Yang’s beach images present a refreshingly different framing of the typical Australian beach scene, in which female bodies or recreational pursuits are often the focus. Instead, Yang’s beach works take immense joy in the male body, and represent a desirous male gaze on desirable male bodies.

The power of being seen

William Yang’s work, intimate and considered, draws on the artist’s own lived experience. Yang’s personal stories inform his spoken-word performances and photography, and he often scribes these stories directly onto his photographic prints. Drawn to people, Yang’s work reveals unsettling narratives in his own life, in the lives of his subjects, and in society. Adept at uncovering the unvarnished beauty and hidden foibles of our lives, storytelling is intrinsic to his practice. The artist spoke with exhibition curator Rosie Hays.

Rosie Hays Are there stories you feel must be told? What draws you to the stories you tell from your own life?

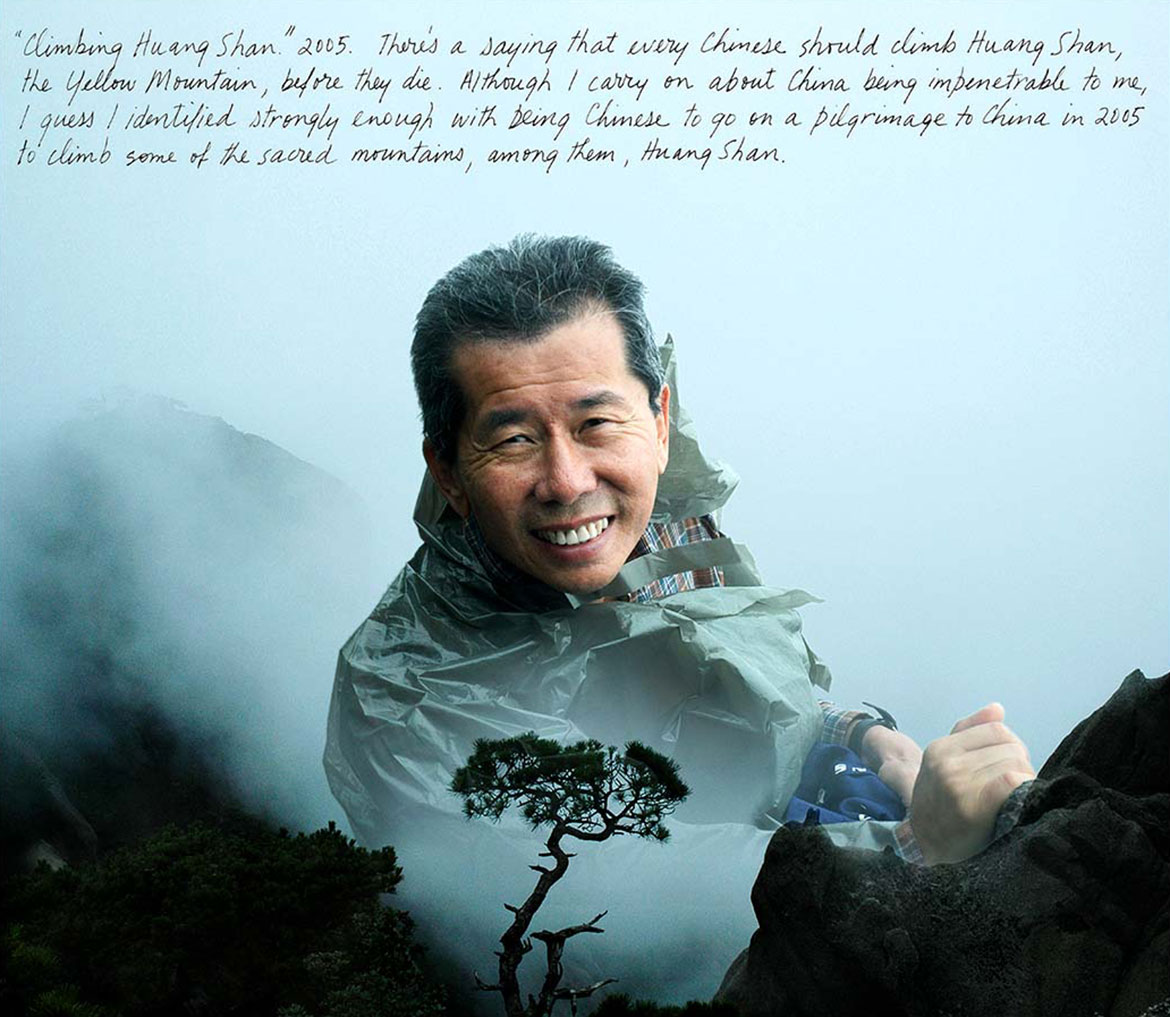

William Yang I [was] brought up as an assimilated Australian. Neither my brother, Alan, or my sister, Frances, or I learned to speak Chinese. Partly because my father’s clan was the Hakka, so he spoke Hakka, whereas my mother’s clan was the See Yap, and she spoke Cantonese, so English was their common language and that was what we spoke at home. My mother could have taught us Cantonese as it was generally left up to her to do that sort of thing, but she never did. She thought being Chinese was a complete liability and wanted us to be more Australian than the Australians. So, the Chinese part of me was completely denied and unacknowledged until I was in my mid-30s and I became Taoist. It was through my engagement with Chinese philosophy that I embraced my Chinese heritage. People at the time called me Born Again Chinese, and that’s not a bad description as there was a certain zealousness to the process, but now I see it as a liberation from racial suppression, and I prefer to say I came out as a Chinese.

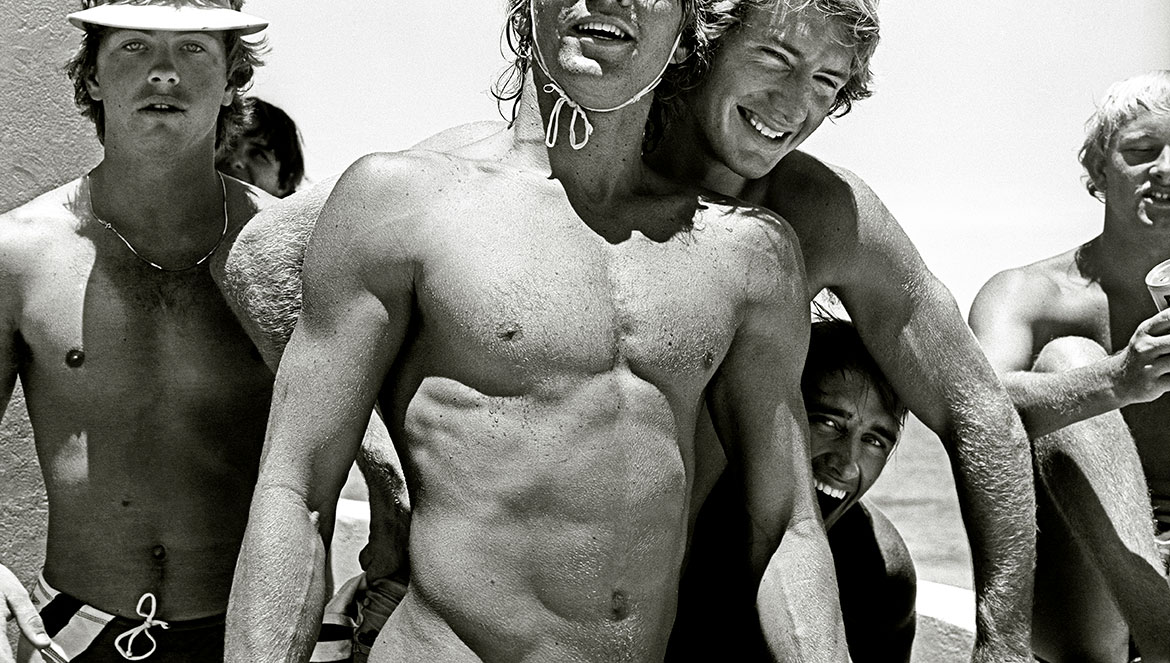

William Yang ‘Chinese New Year Party Year of the Rabbit’ 1999

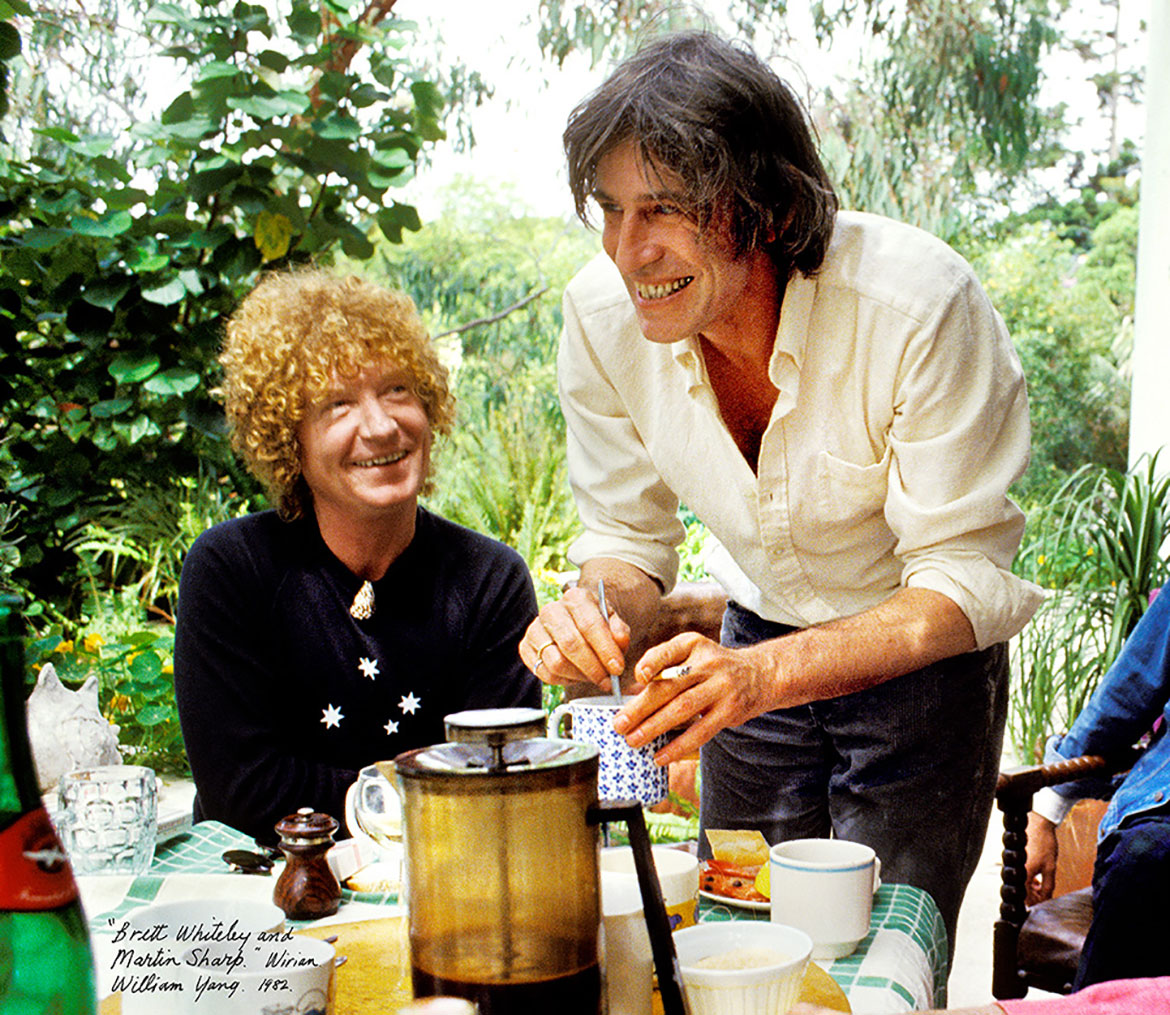

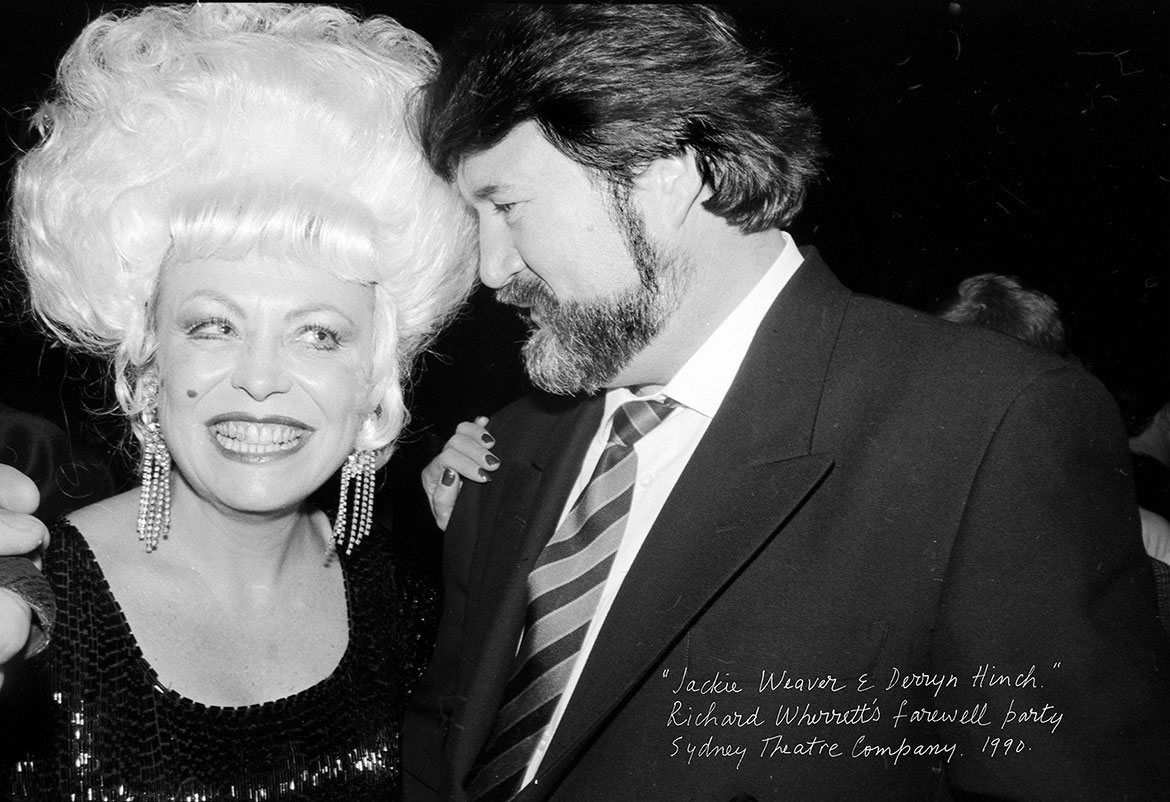

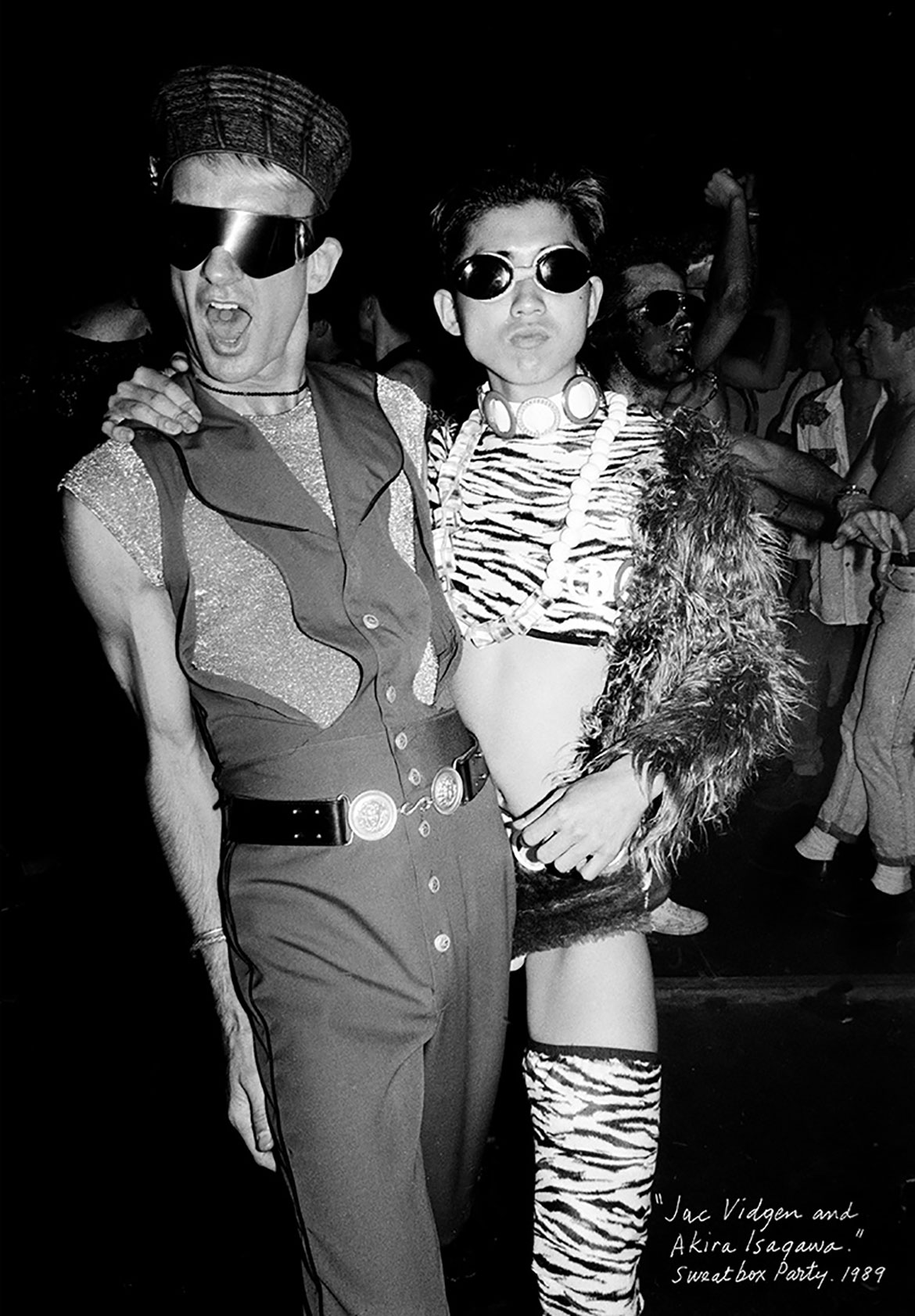

My first big success was my show ‘Sydneyphiles’ at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1977. It was mainly about my social life in Sydney, with portraits of people I had met. Besides my own set of artistic types (I knew Brett Whiteley, Martin Sharp, Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson), I brushed with celebrities on the social rounds working for magazines. The exhibition caused a sensation. I knew then that people were my subject. I found that they wanted to see themselves on the gallery walls, they wanted representation. A compromising photo might cause annoyance, but it was better than being left out. There has always been an appetite for celebrities, well, that was to be expected. A vicarious interest in celebrity life still fuels the media. But I showed many photos of the emerging gay community as well. Australian photos of this type had not been shown in institutions before and it got a mixed reaction. Some said that these works shouldn’t be shown at a public institution, but mostly the pictures were accepted, especially by the gay community. A few were angry with me for outing them, but mostly I was hailed as a hero and was metaphorically given the keys to Oxford Street. I sensed that the mood of the gay community at the time was this: throughout history our community has been invisible. These photos may not be pretty, but we recognise them, and we accept them. We want our stories told.

William Yang ‘Four film directors’ 1981

William Yang ‘Brett Whiteley, Martin Sharp, Wirian’ 1982

William Yang ‘Jacki Weaver, Derryn Hinch. Richard Wherrett Farewell Party, Sydney Theatre Company’ 1990

William Yang ‘Ben Law. Arncliffe’ 2016/2020

These days I don’t take as many photographs. I’m sorting through my collection, trying to get it into some sort of order, and trying to digitise the negatives and the colour transparencies [. . .]. I don’t want to be a photographer who dies leaving a pile of mouldy negatives for someone else to sort out [. . .]. Every time I look through my collection, I am surprised because I have largely forgotten what happened in the past. Photography is a major aid to memory and the photographer a witness to the past. A photograph captures a moment in time. You don’t have to do anything special for this to happen, just press the shutter. There is something in the nature of the camera to freeze these moments in time, and there is something in the nature of the world to change and move on, so these moments never occur again.

In the early 1980s I started to do slide projection. It started off as a way to show my colour photography. At the time the colour printing process, Cibachrome, was expensive, and projection was a cheaper way showing my colour images. In 1980 in Adelaide, I met Ian de Gruchy, who did slide projection as his main art form. I was interested in his dissolve unit — a device using two projectors where the projected images dissolved into each other. Music was used, usually minimal music, and the result was known as an audio-visual. When one projects slides, as in a living room slide show, there is a tendency to talk with the slides, explaining them, and I started to do that. I worked with audio-visuals for seven years during the 80s until I had nine photographic essays, or short stories, to string together into a one man show. It was called ‘The Face of Buddha’ and I presented it at the Downstairs Belvoir Street Theatre in 1989. I lost money on that show, but still consider it a success. Everyone liked the form, story-telling with images and music.

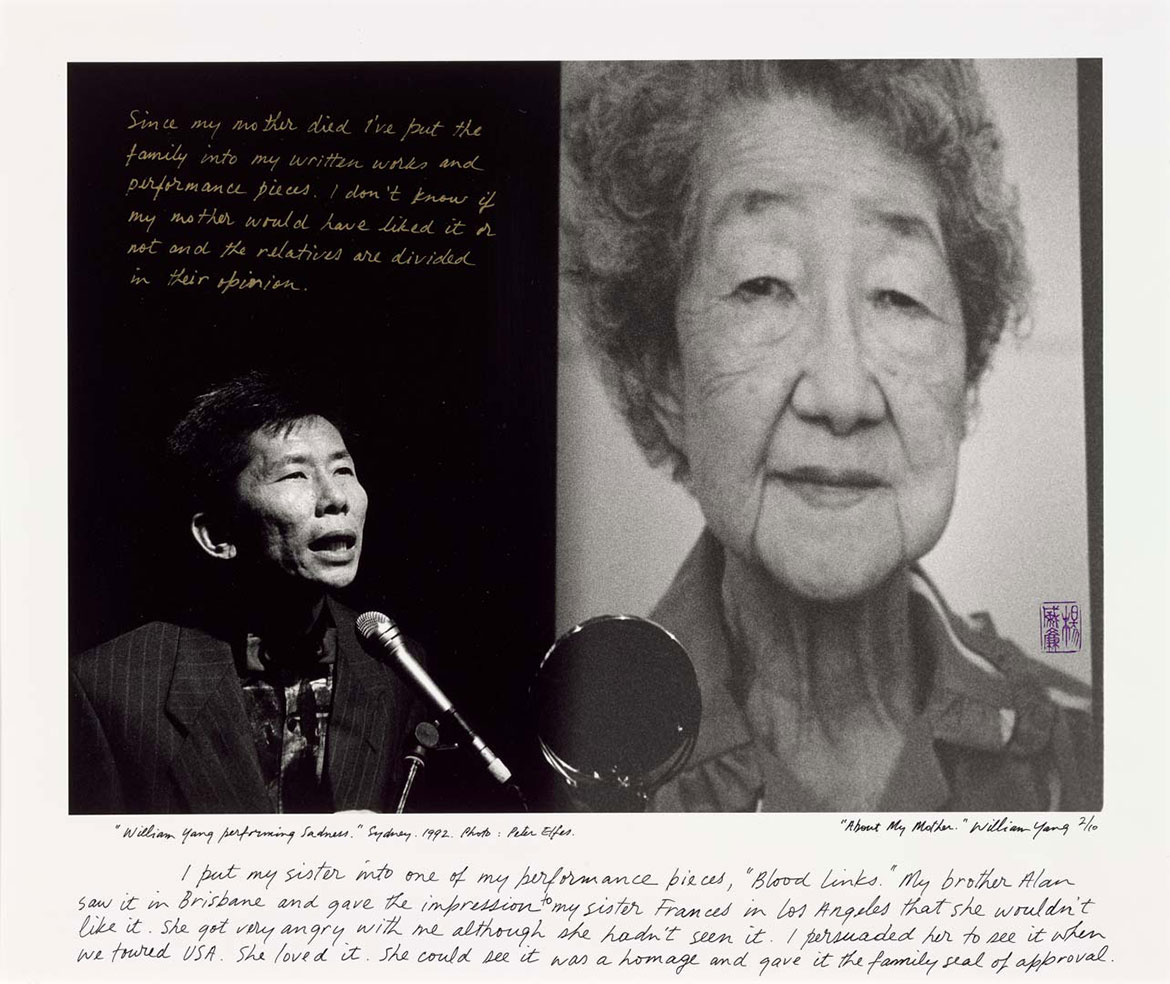

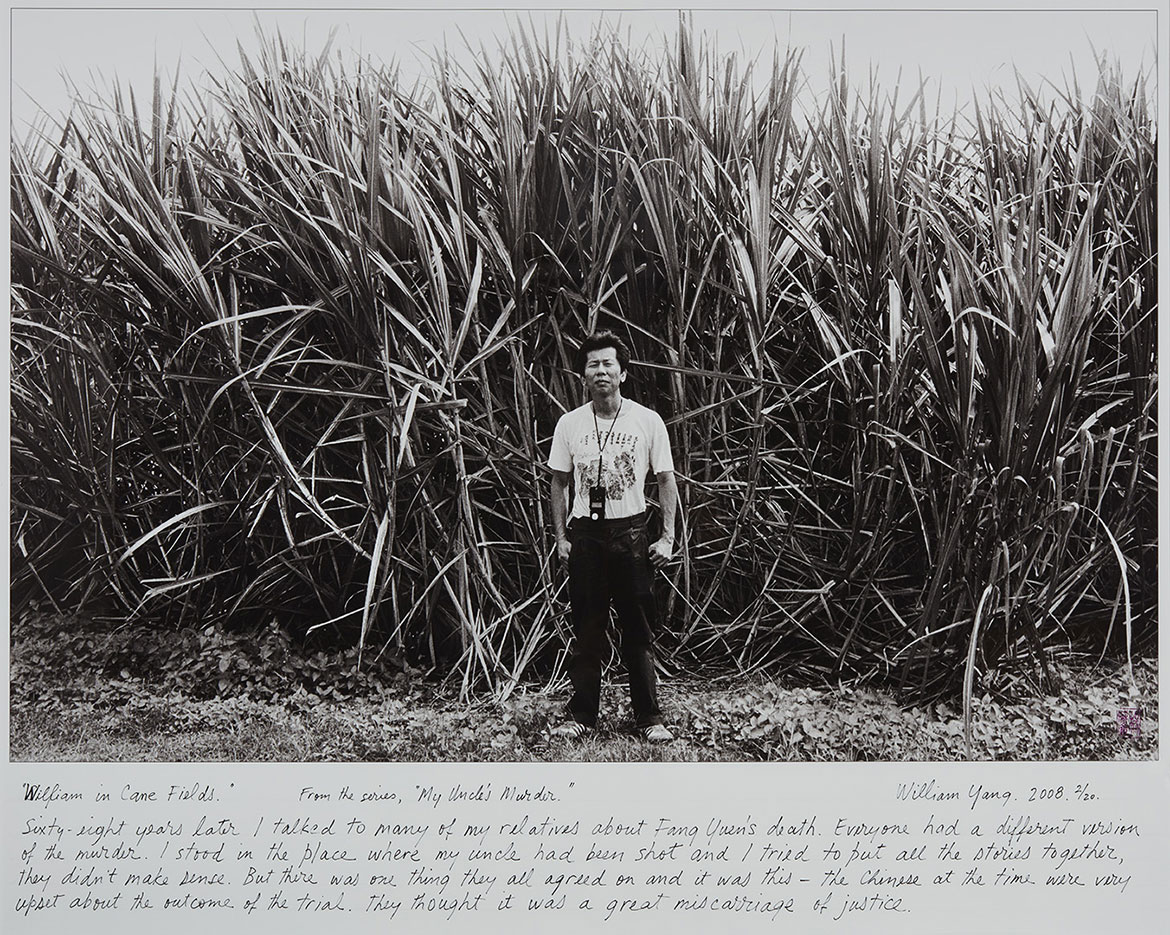

The most popular story was called ‘About My Mother’. I told the story about my mother’s family, how they came to Australia in the 1880s from Guang Dong province in China. My mother’s sister, my Aunt Bessie, married a rich landowner, William Fang Yuen, who was murdered by the white manager on his cane farm at Marilyan in north Queensland in 1922. I got an Australia Council grant to do my third performance piece, ‘Sadness’, in 1992. There were two themes: the first involved the AIDS pandemic in Sydney where many gay men, some of them my friends, were dying; and the second was a trip I took to north Queensland to talk to my relatives about William Fang Yuen’s murder. The two themes formed a powerful story about death and legacy. It was an immediate hit and toured Australia and the world. International entrepreneurs wanted my performance pieces, which they considered unique, not my exhibitions, so I kept doing more performance pieces and they became my main artistic expression.

William Yang ‘William in Cane Fields’ 2008

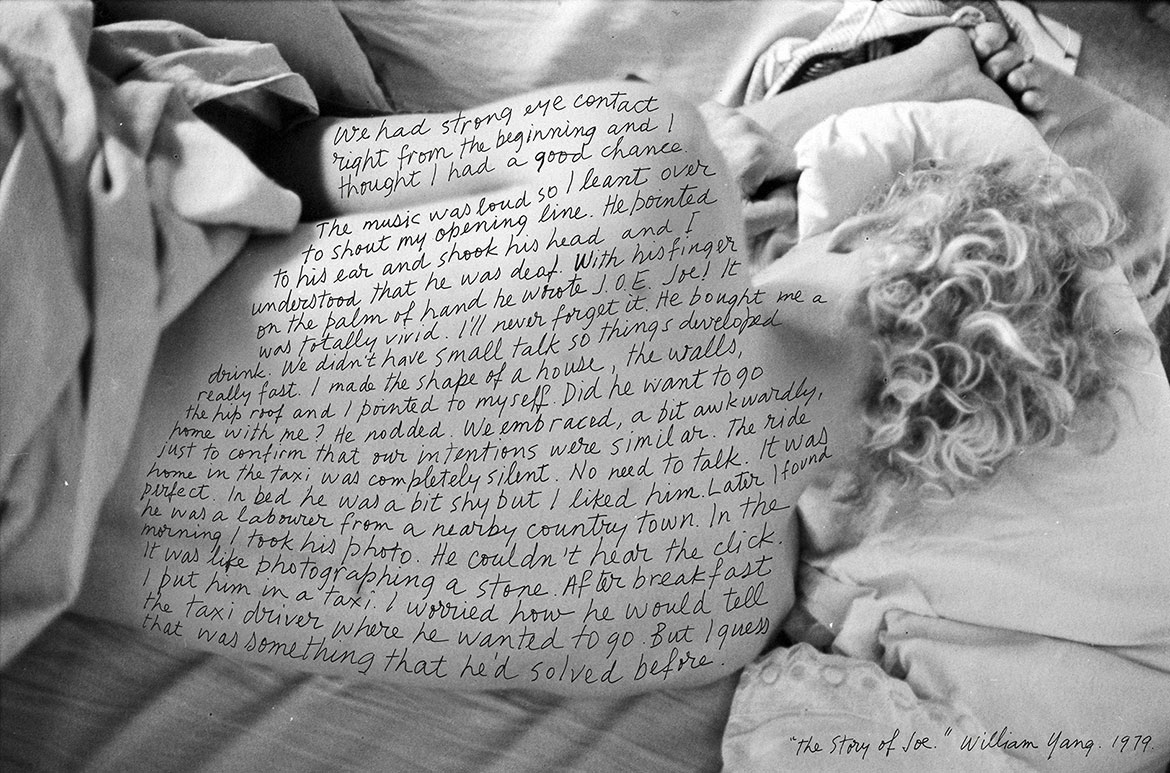

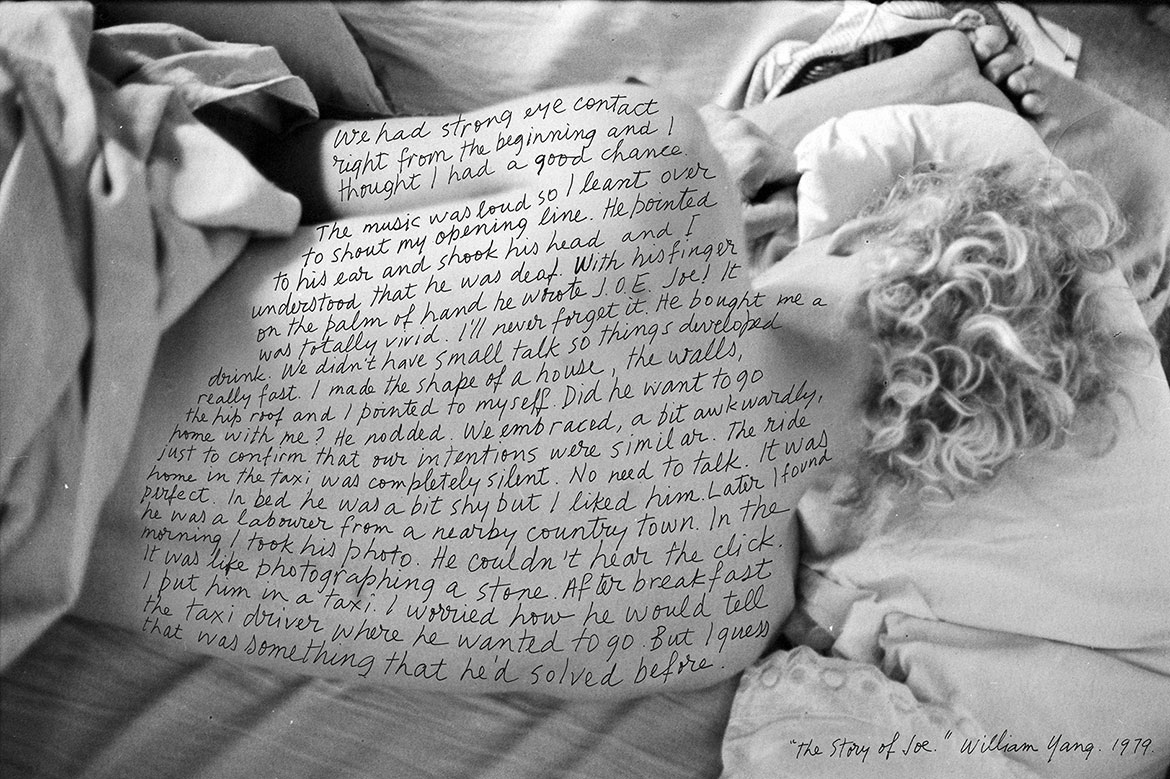

The performance pieces changed my photographic practice. Before the 1990s, I made my living from freelance work. I would do whatever jobs people would pay me money to do. Then I found I could make a living doing my performance pieces, so I didn’t have to work for other people. I was able to channel all my energy into my own work and I became more productive. My performance pieces were about stories and I realised that many of my photos had stories behind them. I started writing the text directly onto the photo with a pen. My first series was about men with whom I had had encounters. All those photos had good stories. I have continued to do written works, as I call them, and the pictures with my handwriting have become the signifier of my work. Now I often choose images because they have a story.

William Yang ‘The Story of Joe’ 1979/2020

Rosie Hays Do you ever feel you’re telling other people’s stories, or are they your stories that happen to intersect with other people?

William Yang When I ran out of my own stories, I wanted to tell an Aboriginal story because I felt the Chinese and the Aboriginal people had something in common: both had suffered under British colonialism. In my commissioned piece ‘Shadows’, I tried to tell an Aboriginal story about a community in Enngonia in north-western New South Wales, and it was successful in that I made myself part of the story, but I felt a little uncomfortable telling their story. Later I found someone, Noeline Briggs-Smith, who could tell her own story, and we did a story-telling duet on stage [called] ‘Meeting at Moree’, where we told alternating chapters of our stories on stage. She [. . .] had a much stronger story than me. She had suffered more and worse injustices than I had, but there were interesting intersections in our stories.

Rosie Hays Something we highlight in the exhibition is your connection to landscape. How would you describe your relationship to nature/the landscape, and has it changed over time?

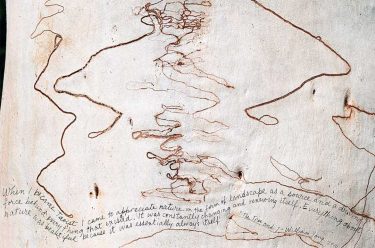

William Yang Most photographers have a go at nature. Everyone has photographed a sunset. I had my first serious encounter with photographing nature when I was recovering from a bad case of hepatitis at Frogs Hollow, Maleny, in 1979. I felt fragile from the illness and taking photos made me feel I could still do things. Looking at the photos now, the pictures are a beginner’s view. That’s the thing about nature: it’s been done a billion times before, and it’s difficult [to] escape cliché, but I had to start somewhere and I got a few good ones.

When I became Taoist, I took on a whole new philosophy. I came to appreciate nature, in the form of landscape, as a source and a driving force behind everything that exists. It was constantly changing and renewing itself. Everything about nature was beautiful because it was essentially always itself. I found I could apply a concept of beauty to nature, at least compared to the human nature I was photographing at the time. Later I began to see nature as a titanic struggle for survival [. . .].

I came to realise that the landscape which moved me the most was the country around Dimbulah in north Queensland (on the Atherton Tableland), where I had grown up. It was part of my identity, part of my idea of home. I had absorbed it, it had imprinted itself upon me, and, although I did not realise it at the time — this was before I had articulated an artistic consciousness — it was there in my consciousness and I could draw upon it. So, in the early 90s, I made several trips up to Dimbulah, checking out the country that I remembered from my childhood. Nothing quite fitted my memories, but perhaps that’s a thing about childhood and memory. Nevertheless, I photographed a series on a medium format camera, trying to recapture memories. Now I enjoy returning to Dimbulah and seeing the landscape. It still triggers off emotions, but I feel they have become more distant. This text is from my print William at Thornborough, 2006:

I have left these places and I have changed. These places still hold me but I move around these hills like a ghost. It is the motherland which formed and nourished me, from where I came, but to which I can never return.

William Yang ‘Return to the place of childhood. Dimbulah’ 2016

William Yang ‘Self Portrait Embracing Storm. Assisted by George Gittoes’ 2019

Rosie Hays What are your aspirations as an artist? What is the aim for your work in the larger sense?

William Yang Two of my most important realisations were, firstly, that I was not white but Chinese, and secondly, that I was not straight, but gay. I probably realised these at an early age, but it took me a long time to articulate the condition and to come to terms with it. Personally, I suffered more pain being a closeted gay than being Chinese. These are both big themes in my work. When I started including gay work in my exhibitions, some photographers told me it [was] a phase I was going through and I’d be better off dealing with universal issues. They were right, in a way, because by continuing to deal with marginalised issues, my audience base is much smaller. I would probably have made more money sticking with celebrity lives and continuing the status quo, but it is important for me to talk about being gay and to talk about racial difference, even if they are commercially unpopular subjects. Nowadays, there is more acceptance of being gay here in Australia, and likewise, there is more awareness of racial difference, but in the wider world this is not always the case. It is a cause worth pursuing, and documentary photography with a personal story thrown in is a good way of doing it. I want to acknowledge the activists around the world that have made social change happen.

William Yang ‘Climbing Huang Shan’ 2005

William Yang ‘Jac Vidgen and Akira Isogawa, Sweatbox Party’ 1989

I want my work to embrace my life. I’ve managed to live to a mature age — I was fortunate not to die young as many of my colleagues did during the AIDS pandemic. One lives a life, and I am not the same person as I was when I was younger. Then I had more energy, had more opinions, some of them obnoxious — in short, I had many of the traits of a young person that old people like to complain about. But one learns from life, and I have lived to this age and can see there is a shape to one’s life. It has to do with the things you believe in and the choices you make (I always knew being an artist would be a hard road), it is shaped by external forces beyond your control, and it is also shaped by luck. Still, I consider my life a fortunate one.

I think I like stories because they are about people and the world. They somehow embrace humanity. I would like my art to convey feelings, emotions, what it is like to be a sentient human: experiencing joy, laughter and sadness, to realise we are vulnerable, that we have our failings, we do bad things, but we are capable of forgiveness, kindness and love.

Rosie Hays is Associate Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA She spoke with the artist in 2020. This is an edited excerpt of the original interview, which appears in the exhibition publication William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen, available at the QAGOMA Store and online.

‘William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen’ / Gallery 4, Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) / 27 March to 22 August 2021.

#QAGOMA