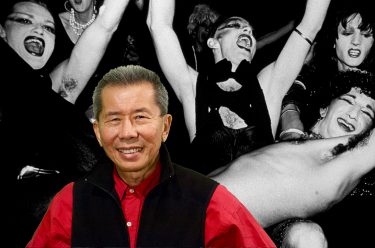

William Yang’s work, intimate and considered, draws on the artist’s own lived experience. Yang’s personal stories inform his spoken-word performances and photography, and he often scribes these stories directly onto his photographic prints. Drawn to people, Yang’s work reveals unsettling narratives in his own life, in the lives of his subjects, and in society. Adept at uncovering the unvarnished beauty and hidden foibles of our lives, storytelling is intrinsic to his practice.

Watch | Director Chris Saines discusses ‘Self portrait #1’

William Yang

William Yang’s unflinching photographic gaze draws from the documentary tradition. Since the 1980s, Yang has displayed an unyielding persistence in unearthing stories that society, or even his subjects, might prefer to remain hidden. His instinct and passion is to present the whole, flawed story, not just the glossy surface.

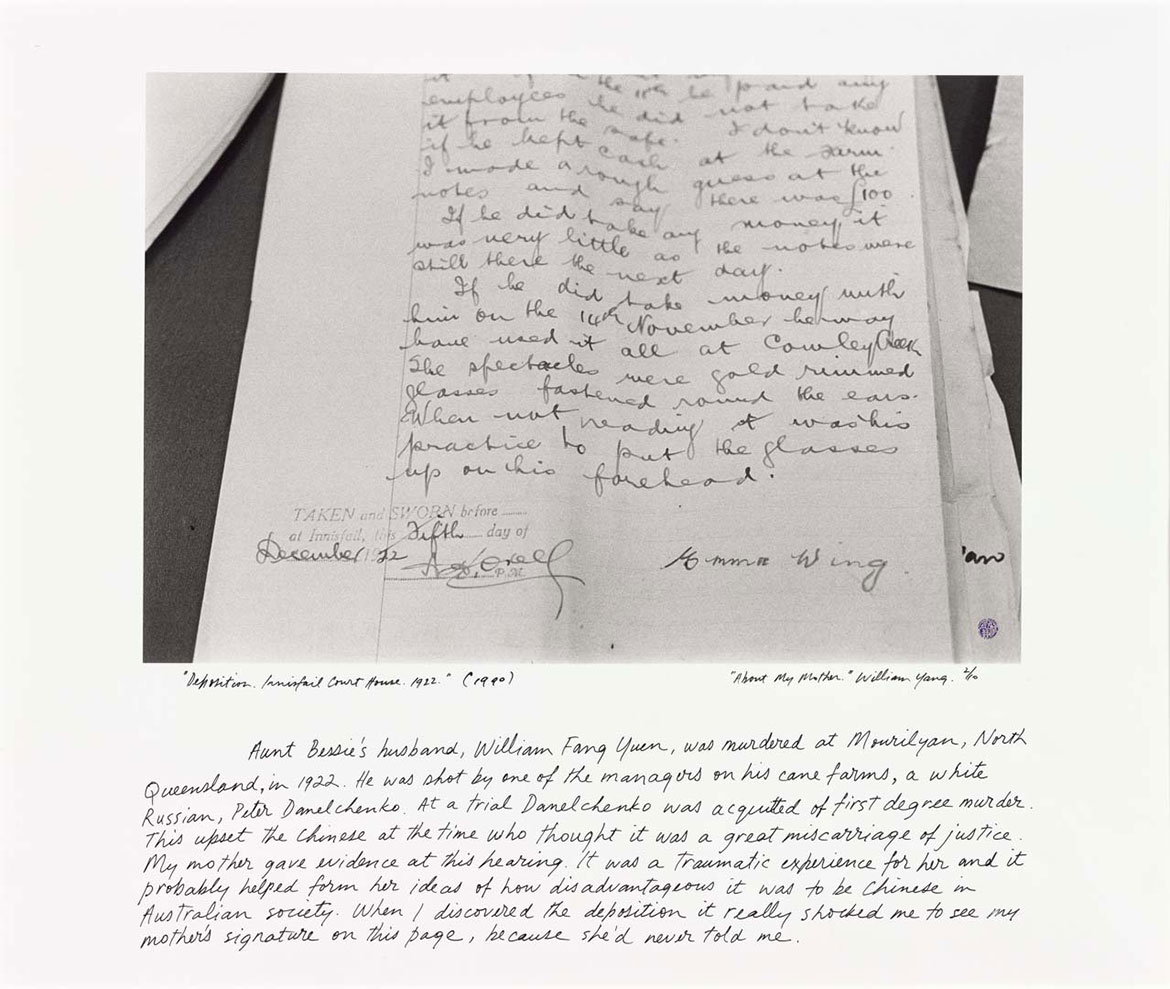

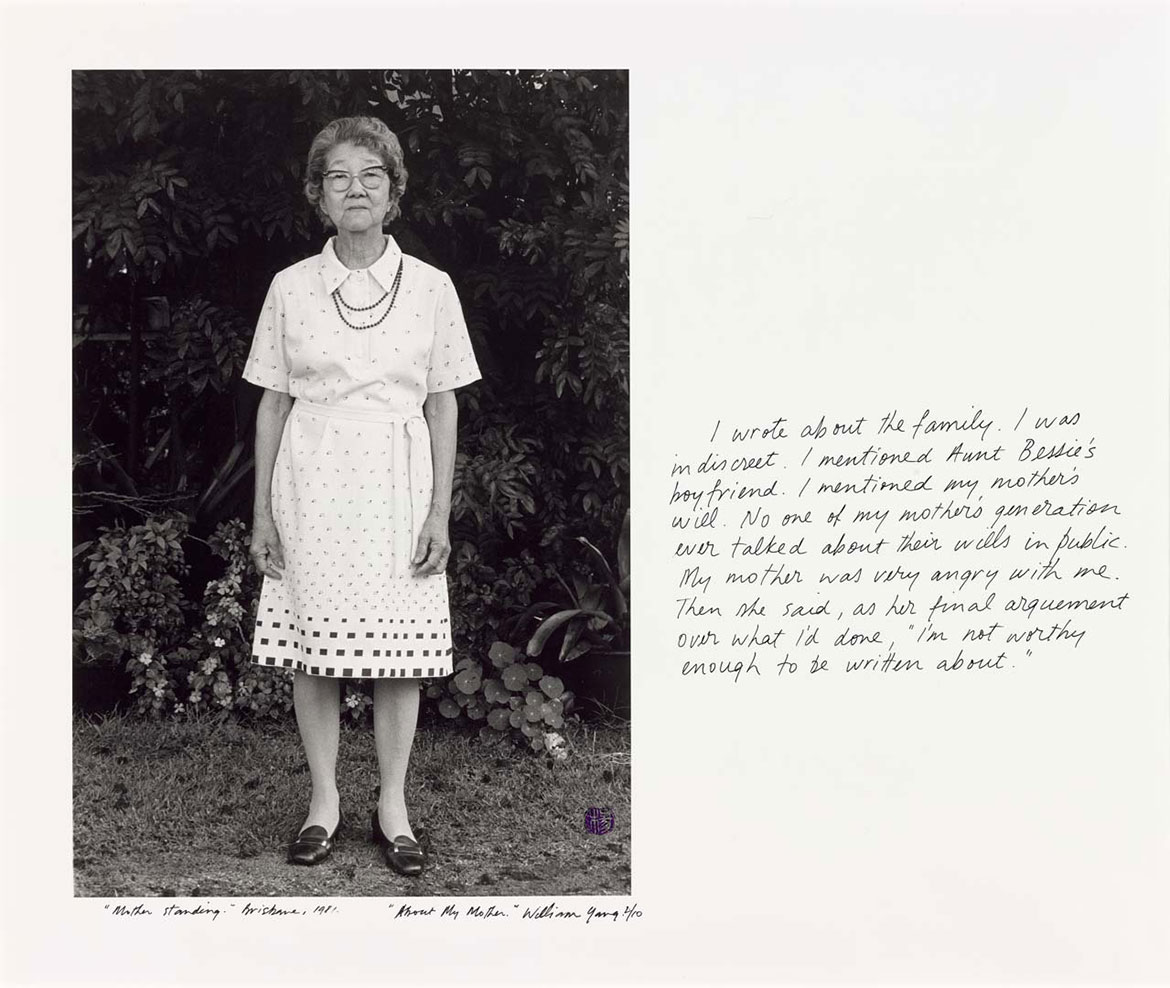

With stories such as his uncle’s murder, Yang courts his family’s disapproval by airing hidden family stories, balancing potential indiscretions with the importance of telling real stories that reveal experiences or communities often left out of public discourse.

‘Deposition. Innisfail Court House. 1922 (1990)’ 2003

Yang grew up in a family who disavowed their Chinese heritage in pursuit of assimilation and acceptance in Australian society, he recounts that it wasn’t until a primary school classmate cruelly taunted him with the racist rhyme ‘Ching Chong Chinaman’ that he realised he was Chinese. Of this time, he has said:

[My mother] thought being Chinese was a complete liability and she wanted us to be more Australian than the Australians. So the Chinese part of me was completely denied and unacknowledged until I was in my mid-thirties and I became Taoist.1

‘Mother standing. Brisbane. 1981’ 2003

In the mid 1980s, Yang met Yensoon Tsai, a young Taiwanese woman who would become a close friend. Tsai taught Yang the tenets of the Chinese philosophy of Taoism, which led him to explore his Chinese–Australian identity.

Throughout the late 1980s and 90s in Australia, multicultural stories emerged across various art forms. Yang was part of this wave of artists rejecting a suppression of their cultural histories, and who instead wanted to highlight and celebrate diversity. Yang travelled throughout regional and urban Australia documenting the lives of Chinese–Australians, and the landscapes reflecting the legacy of the Chinese in Australia, such as religious shrines and mining sites. At this time, Yang also visited China regularly and started to interrogate his identity. Of this period, Yang observed:

People at the time called me Born Again Chinese, and that’s not a bad description as there was a certain zealousness to the process. But now I see it as a liberation from racial suppression and I prefer to say I came out as a Chinese.2

‘Self portrait #1’ 1992

Self Portrait #1 is a landscape work (in the way Yang talks about landscape which is often rooted in people and place and memory) as much as it a portrait work. Capturing the landscape is part of Yang’s somewhat diaristic approach to processing his social and physical environment.

When Yang returns to the Queensland landscape from his childhood, he characterises it as a site to escape from. He needed to escape from racist school bullying, constrictive family expectations, and the dread that his sexuality may be met with disapproval. Yang revisits his childhood home regularly, and some of his most potent performances and photographs come from connecting family and place. The series ‘My Uncle’s Murder’ — and its recounting of an injustice borne of racism dating from 1922 — resulted from such a trip. In his later works, he makes an uneasy peace with these past experiences that are embedded in the landscape of his youth.

Rosie Hays is Curator of ‘William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen’, and Associate Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 William Yang, email interview with Rosie Hays, 2020

2 William Yang, Life Lines #11 – William in scholar’s costume (1984) 1984/2009.

#QAGOMA