The Gallery recently acquired this subtle yet powerful work by Yael Bartana, whose statements on the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians have come to characterise her practice.

Yael Bartana uses photography and video to explore Jewish identity. Born in Afular, Israel, in 1970, to whom she describes as very Zionist parents,(1) Bartana characterises herself as an ‘artist from Israel’ rather than an ‘Israeli artist’, as a way of questioning the manner in which nationality defines identity.(2) Her work Summer Camp 2007 was included in the film program Promised Lands, presented by the Gallery’s Australian Cinématheque as part of ‘The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (2009–10). Bartana also represented Poland at the 2011 Venice Biennale with the highly acclaimed film trilogy And Europe Will Be Stunned 2007–11.

Jewish–German photographers Leni and Herbert Sonnenfeld (1907–2004 and 1906–72 respectively) created some of the defining images of Jewish people of the twentieth century. During their long careers they documented the rise of the Nazis in Germany in the 1930s, the establishment of the state of Israel, and Jewish immigration to the United States. In 2005, the Beit Hatfutsot (Museum of Jewish People) in Tel Aviv acquired the Sonnenfelds’ photographic archive. This collection includes images of their visit to Palestine, and others from a German training camp for young Jewish pioneers. It is these images that Bartana references in her series ‘The Missing Negatives of the Sonnenfeld Collection’, of which numbers two, twelve and seventeen have been recently acquired for the Collection.

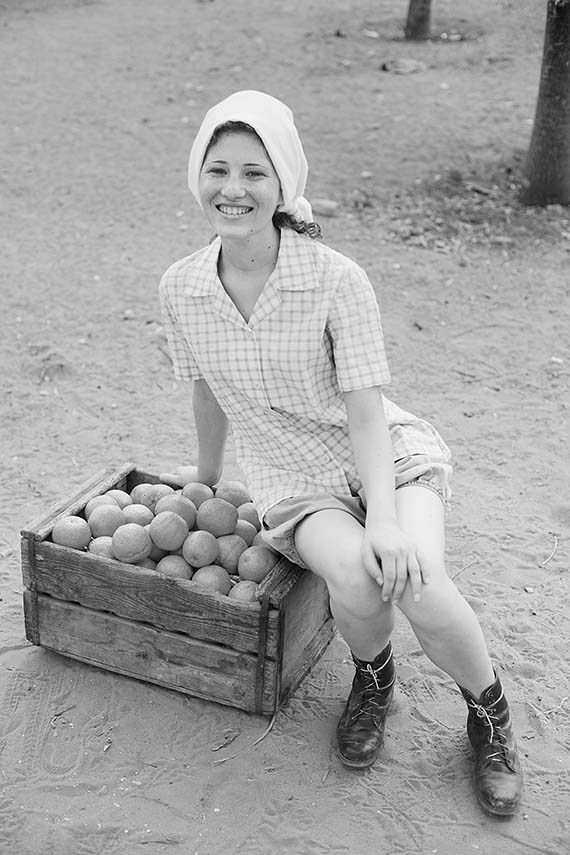

For this body of work, Bartana used both Israeli and Palestinian models to reimagine images from the archive. The models pose with richly metaphorical fruits — pomegranates, oranges, and grapes — or hold tools, seemingly poised for action in a bare landscape. The different origins and identities of the models is not at first apparent; what strikes the viewer is a sense that these optimistic youths are working to build and nourish their future together. Such subtle and yet powerful statements on the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians have come to characterise Bartana’s work.

Many of the compositions in the series also reference Russian socialist realism. As artist and curator Noah Simblist points out, many of the first ‘Jewish immigrants to Palestine were secular young European and Russian idealists’, and who hoped to overcome the bookish stereotype of the Semite with strong men and women who worked the land. This was compounded by the romanticised socialist vision, in which the individual shaped themselves and the nation through their labour on the land.(3) This idealism resonates in the Australian context: Works in the Gallery’s Collection, such as Godfrey Rivers’s Woolshed, New South Wales from 1890, explore a similar colonial romanticisation of physical labour and ‘living off the land’. In ‘The Missing Negatives of the Sonnenfeld Collection’ series, Bartana draws on imagery that has contributed to defining the state of Israel in order to poetically question the historical and colonial construction of national identity.

Endnotes

1. Nicola Trezzi, ‘Re: Diaspora: Yael Bartana, Elad Lassry, Ohad Meromi and Daniel Silver in Correspondence’, Flash Art, vol.42, October 2009, p.68.

2. Joshua Mack, ‘I didn’t want to make a documentary’, Art Review, vol.20, March 2008, p.66.

3. Noah Simblist, ‘Revolutionary tourism: Land, labor, and loss in Yael Bartana’s Summer Camp’, Art Papers, vol.32, no.6, November and December 2008, p.34.