Renowned Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s The obliteration room 2002–present is an interactive work initially developed by Kusama in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery as a children’s project for ‘The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ in 2022.

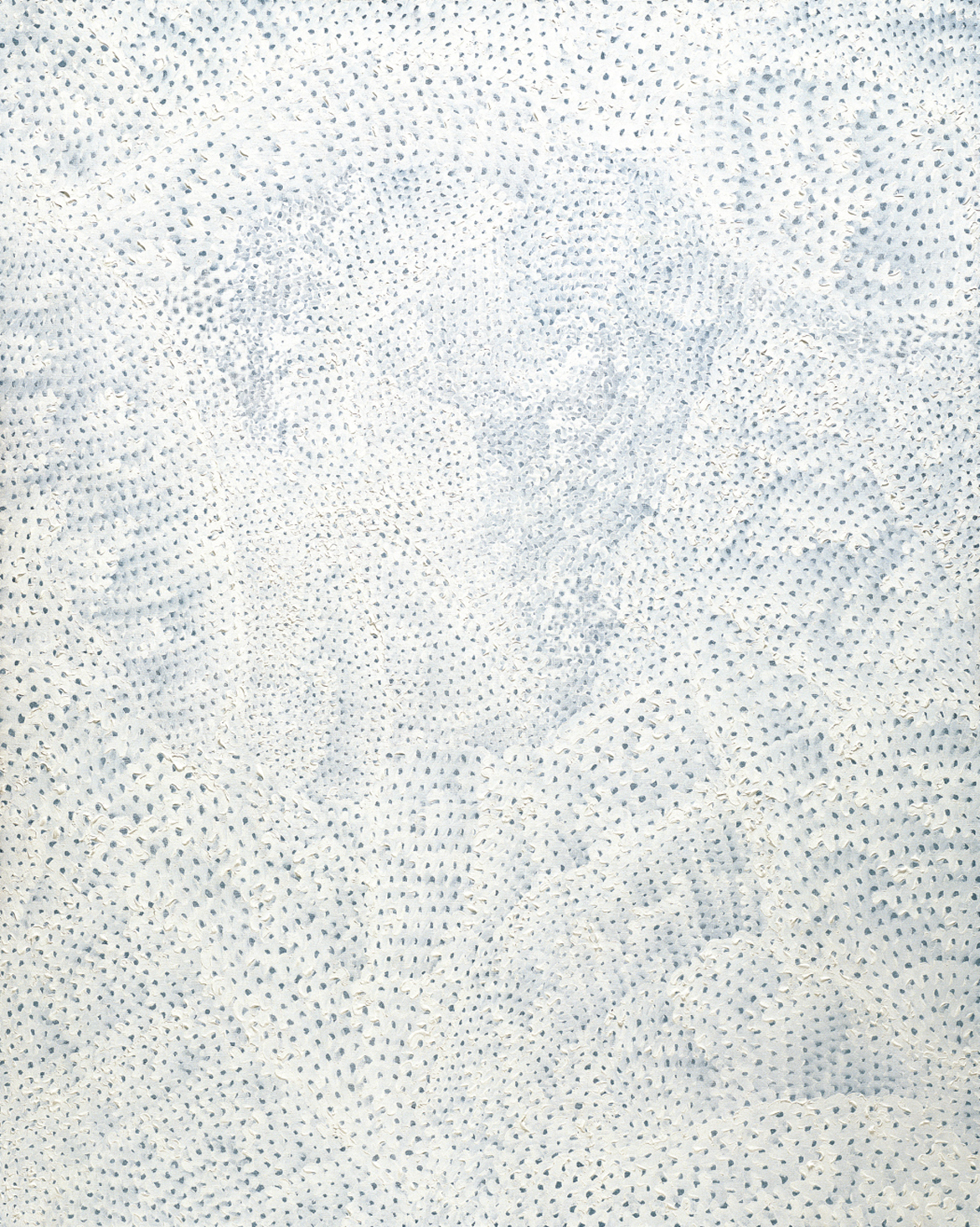

The obliteration room consists of a domestic environment recreated in the gallery space, complete with locally sourced furniture and ornamentation, all of which are painted completely white. While this may suggest an everyday topography drained of all colour and specificity, it also functions as a blank canvas to be invigorated — or, in Kusama’s vocabulary, ‘obliterated’ — through the application to every available surface of brightly coloured stickers in the shape of dots. The choice of a domestic environment with specifically local characteristics is intended to create an air of familiarity that makes participants, especially children, comfortable enough to engage with the work with little or no prompting.

Dots first emerged in Kusama’s work in the early 1960s as the structural inverse of the Infinity net paintings (illustrated) that preoccupied her after 1958, as the negative spaces between the loops of her painterly netting. During this period, dots began to appear on the surfaces of her sculptures and installations, which recalled the hallucinations she had suffered as a child, in which her surroundings were entirely covered with repeating patterns. Later in the decade, dots had developed into an artistic strategy that the artist described as ‘self-obliteration’. A prominent feature of her ‘happenings’ and performances of the period, and usually daubed onto the bodies of participants, dots symbolically neutralised the ego, which Kusama blamed for the horror and destruction resulting from warfare.

Kusama’s dots have proliferated as her installations have grown in scale and ambition, and she continues to frame the dots as traces of her own childhood trauma. The past decade in fact has seen direct representations in the artist’s work of an idealised, ‘lost’ childhood. The exuberance of children buzzing around The obliteration room, stickers accumulating on its clinical surfaces, bears a striking resemblance to this imagined childhood. Indeed, the work functions by mobilising the desires of children to transgress the ‘look but don’t touch’ restriction of conventional museum culture by associating this sensibility with that of parental restrictions in the family home.

The white room is gradually covered with stickers over the course of the exhibition, the space changing measurably with the passage of time as the dots accumulate with the help of thousands of collaborators. Such is the appeal of the work, particularly on social media, that its popularity has proliferated around the world. The extraordinary capacity of Kusama’s work, which adapts to diverse contexts and audiences, underlines the fact that, at 85 years of age, she is more of her time now that at any point in her long career.

#QAGOMA