“Artists handle their works without gloves, so why do Gallery staff need to wear white gloves to handle paintings once they enter a Gallery’s collection?” I hear you ask.

It is sometimes said that in Museums and Galleries we work in a parallel universe; a basic premise of collection care and conservation at QAGOMA often being the maintenance of works in the condition they left the artist’s studio. No matter how an artist handled their work during creation, once a work enters our Collection, it is handled with utmost care.

New fingerprints, dents and other scuffs are unacceptable and are minimised during handling through a few simple but effective measures. For paintings, preventive conservation measures include handling frames for unframed paintings, backing boards and handles, and of course wearing gloves to prevent acids and other oils from your hands dirtying the edges.

DIVE DEEPER: More conservation projects unveiled

SIGN UP NOW: Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest announcements, acquisition highlights, behind-the-scenes features, and artist stories.

During our recent Collection Storage Upgrade, the Queensland Art Gallery’s collection storage space expanded in line with architect Robin Gibson’s original intent for a mezzanine storage level within the existing collection space, because of this over 1300 paintings required relocation.

The method of movement for most include stacking paintings together on trolleys. Paintings are individually assessed over a number of weeks, front and back, by a paintings conservator to determine which of the four preventive measures are to be taken to ensure safe movement:

1. placement in a handling frame, box or stillage to protect unframed paintings and delicate gilded frames;

2. soft wrapping of delicate surfaces to prevent scratching;

3. a cardboard only interleaf for more sturdy framed paintings; and

4. single transport only, for very delicate works that could not be stacked.

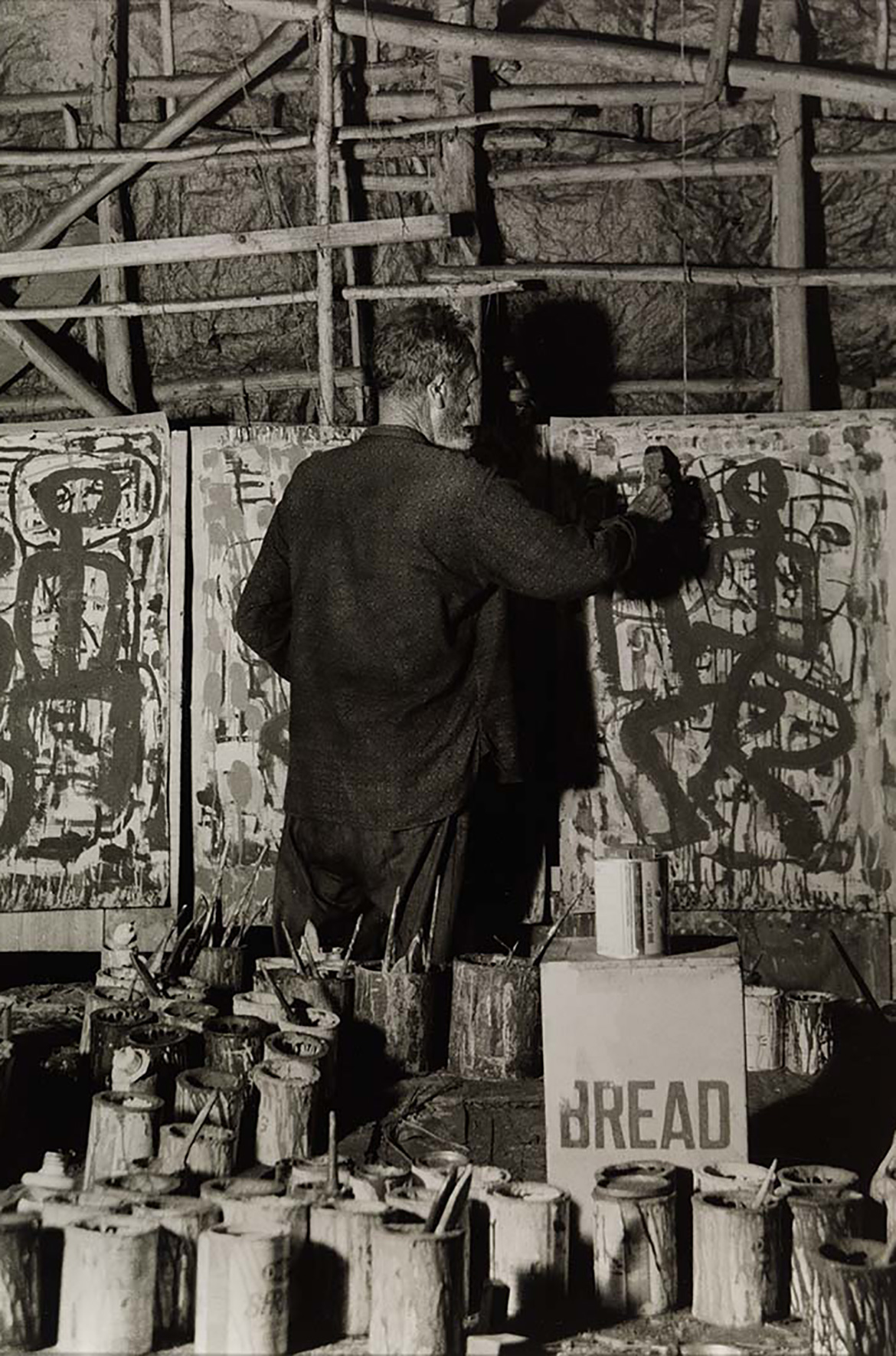

Dedicated teams of art handlers work methodically through the list of works to prepare them for the move; QAGOMA workshop produced handling frames and stillages and technical staff fitted out the paintings. All artworks require custom storage solutions and technical problem solving to ensure they can be safely moved. In the case of Roger Kemp’s Tapestry – Tableau (Vertical and horizontal concept) 1972, this work was fitted into a handling frame.

A handling frame is a temporary wooden frame that is fitted to a painting using clips on the reverse. The handling frame is removed for display, and the clips folded in so that they are not visible. The painting is returned to the handling frame for transport after display. The handling frame enables large and fragile paintings to be moved without touching their surface. Sometimes lids are added to the handling frame for works which are light sensitive – those which contain fluorescent colours or paper collage for example. Some handling frames are also wrapped in plastic to protect dust settling on soft paint surfaces.

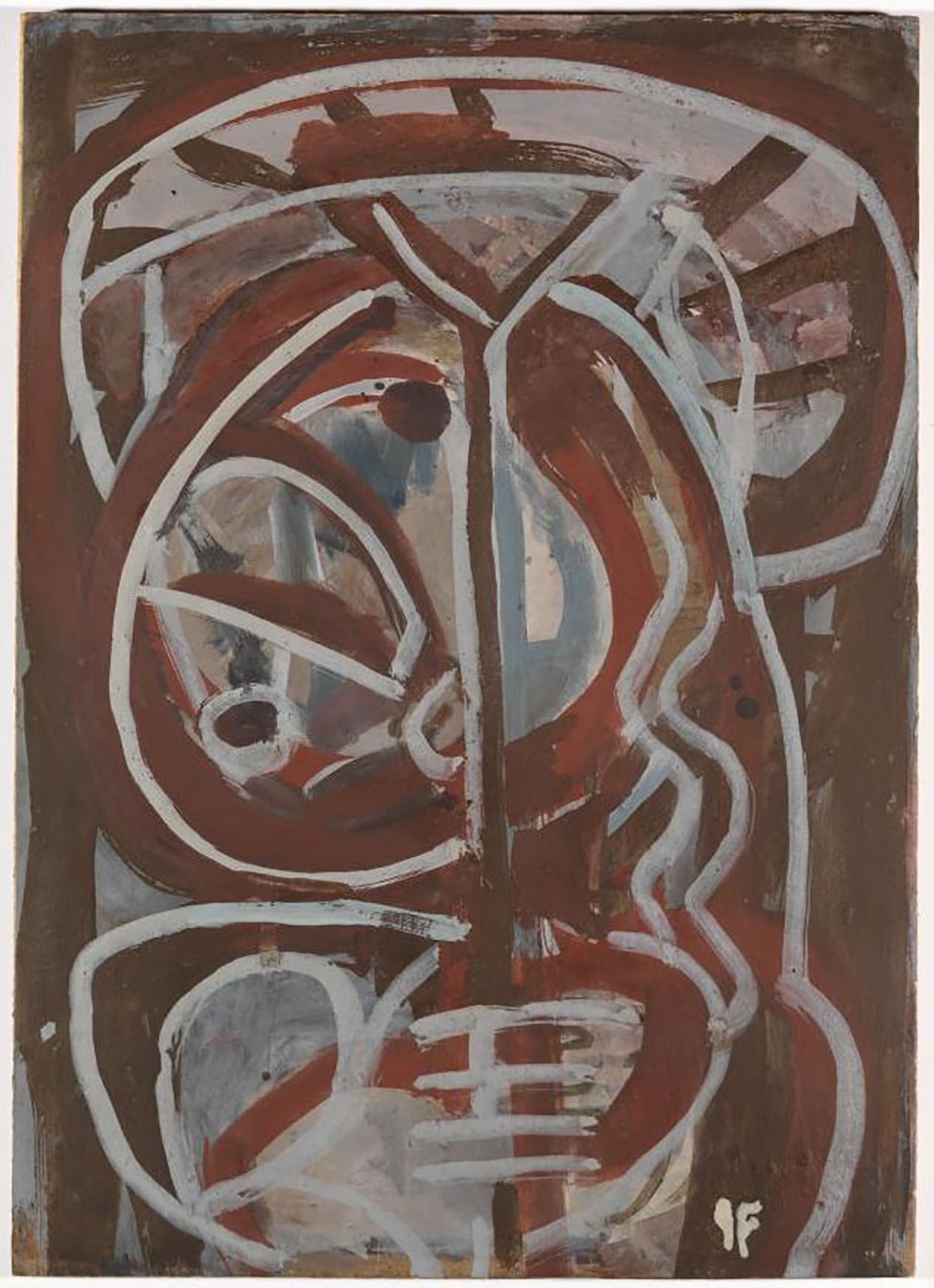

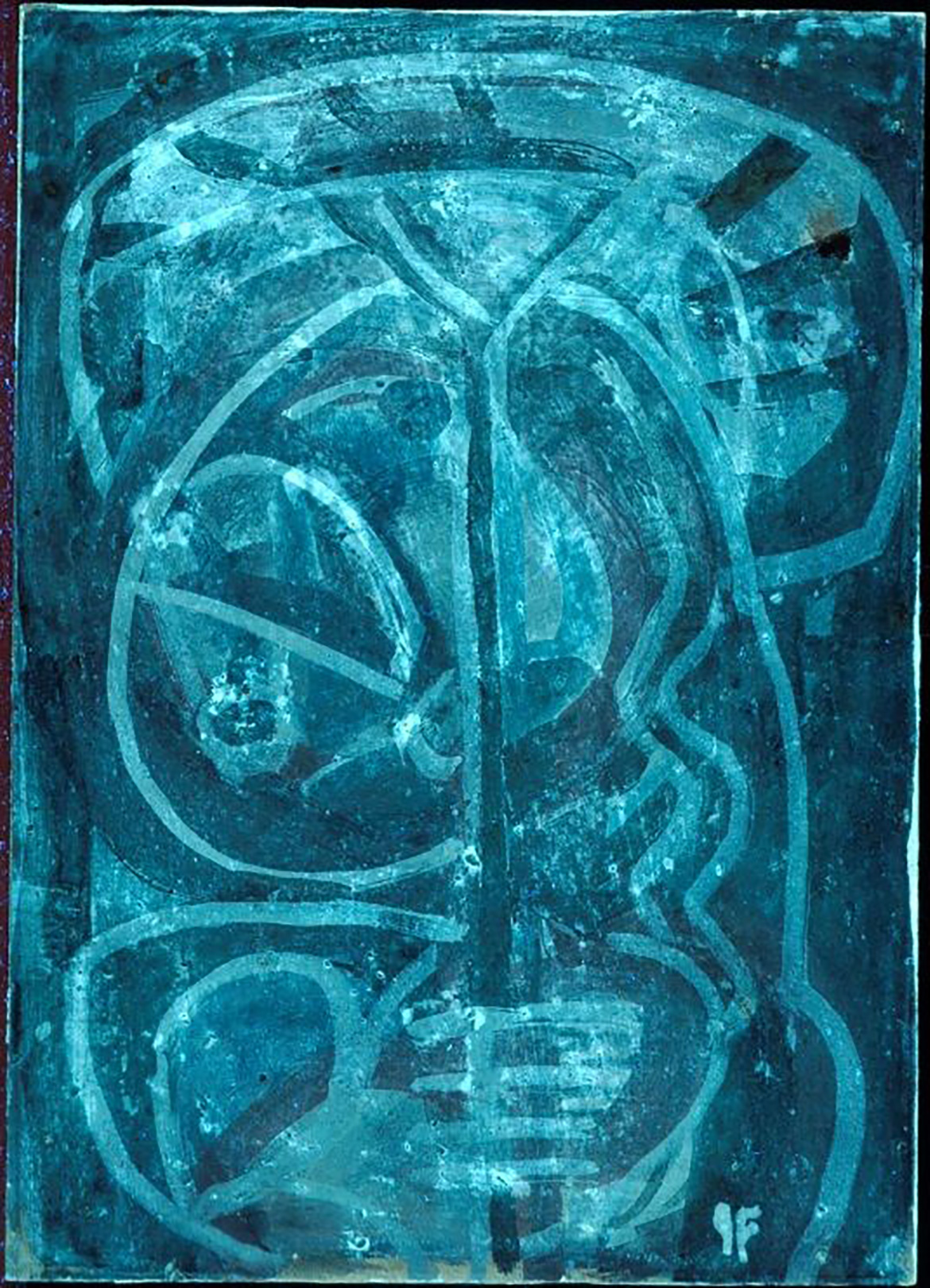

Roger Kemp’s Tapestry – Tableau (Vertical and horizontal concept) 1972 was inspected and because of its size, and its vulnerable paint at edges, it was fitted into a handling frame for protection. The painting came into the collection in 1994 unstretched and was stretched onto a temporary strainer for consideration for acquisition. In 1999 the painting was restretched onto a new custom made western red cedar stretcher by Gallery conservation staff.

The painting, due to its large size, had also suffered from difficult handling: its canvas was dented and there were some creases and some loose paint at the edges – all of which was treated at the time of stretching. Following stretching, a grey acid free cardboard backing board was added by screwing into the strainer to prevent accidental impact to the back of the canvas. In preparation for fitting into a handling frame, clips were added to the reverse of the stretcher.

The reverse of Roger Kemp’s Tapestry – Tableau (Vertical and horizontal concept) 1972 highlighting the bottom left corner showing that the tacking edge does not continue all the way around the underside of the painting to the back – creating a vulnerable canvas edge. The grey board backing is also seen in this cornet detail. White cloth cotton tape can be seen underneath the staples used when the work was restretchd in 1999. This tape prevents the staples damaging paint.

The clips are a multi-purpose foldable brass fitting for paintings, they are an Australian invention and are now used worldwide for the transport of paintings in handling frames. The fittings are designed so that they can be screwed to the reverse of the painting on one side, folded out and bolted to a handling frame on the other side. The handling frame can then be slid into a crate, wrapped, or moved on a trolley. In this way, a painting can be packed with nothing touching its surface. Previously the clips had been added to the reverse of the stretcher of Roger Kemp’s painting and our video shows the next stage of fitting the work into the handling frame.

Job completed, the painting can now be safely moved.

Anne Carter is Conservator, Paintings, QAGOMA

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Hear artists tell their stories / Read about the Australian Collection / Subscribe to YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

#QAGOMA