For more than four decades, Judy Watson has created powerful, ethereal works of art channelling the stories of her family’s Waanyi Country in north-west Queensland. ‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri‘ (tomorrow the tree grows stronger) at the Queensland Art Gallery from 23 March until 11 August 2024, is a comprehensive survey of the renowned Queensland artist’s incisive meditations on colonial, social and ecological concerns. It is her most extensive solo exhibition to date.

Watson is one of our most resolute and formidable storytellers — an artist who never falters in holding historical and present-day injustices to account. Since the early 1980s, Watson has drawn powerful stories and profound truths from the Country of her matrilineal family and fashioned them into fluid and ethereal works of art. In the process of their making and in their visual effect, her unstretched canvases are saturated with the polemical currents of our colonial, social and ecological history.

Watson was born in 1959 in Mundubbera, south-east Queensland, but maintains an abiding connection to her Waanyi Country in the state’s north-west through an unbroken line of female ancestors. It is from this spiritual home that her work emanates, wheresoever it grapples with local history, memory, grief and loss. As Hetti Perkins has noted, ‘Judy Watson paints the country not from outside it but within it’.1 Her work is not only a persistent and haunting requiem for cultural loss, but also an unbowed declaration of cultural reclamation.

Judy Watson installing ‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri’

Judy Watson with ‘walama’ 2000 during casting

Watson is one of Australia’s most globally collected and exhibited artists, and this exhibition is the most expansive of her career to date. ‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri: Judy Watson’ includes more than 120 works that chart the wide reach of her artistic concerns. Its title, from a poem in Waanyi language by the artist’s son Otis Carmichael, translates as ‘tomorrow the tree grows stronger’. The deep time of Country, the long shadow of colonisation and the vital energy of feminism are all illuminated by Watson’s ability to tell stories that might otherwise be erased from the landscape.

Through the undulating fluency of forms in her printmaking, painting, drawing, sculpture, video and installation works, Watson summons up urgent human ideals. These concerns and archetypes linger, seducing the viewer as Watson returns time and again to the creek or the midden to strengthen her story of the enduring occupation of Australia’s First People, and to refuse its elision from history.

Country is ever-present in this work, inextricably interwoven in the matrilineal profiles and portraits of the Watson women and records of her family’s place. Watson re-humanises the contents of archives and institutions, in which she has often worked as an artist in residence, drawing historical complexity from bureaucratic accounts of massacres and atrocities. She has also explored handwritten journal entries from Matthew Flinders’s expeditions, with their rudimentary records of the Aboriginal people they encountered. For the first time, this exhibition presents Watson’s video works as a significant group, as well as previously unexhibited original prints from the late 1970s and early 1980s which are fascinating precursors to Watson’s artistic project.

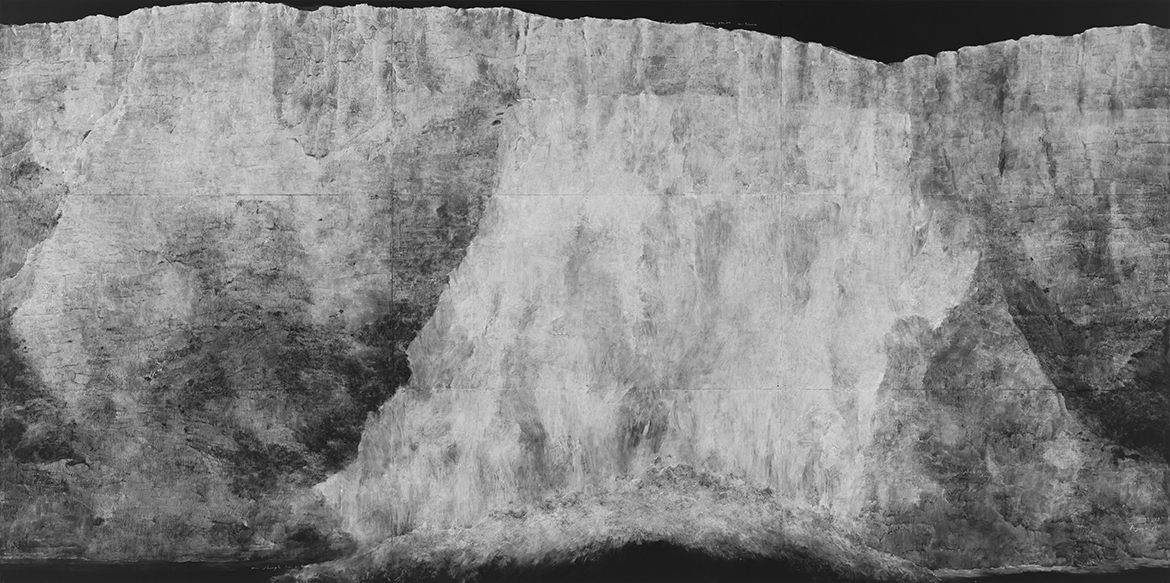

A key work, sacred ground beating heart 1989, pulses with the subterranean water that feeds the springs, rivers and creeks in Waanyi Country and whirls with static electricity and dust, drawing on the enduring spiritual and life forces of ancestors in whose footsteps the artist treads.

Judy Watson ‘sacred ground beating heart’ 1989

Watson’s practice has long been centred on truth-telling, particularly in regard to protecting the environment, government policy towards Indigenous Australians, and the role of institutions that have collected and house Indigenous cultural material. Watson refers to her research-driven practice as ‘rattling the bones of the museum’, bringing her lens as an Aboriginal woman to bear on its content. From the beginning of her journey, she has searched relentlessly for truth and meaning by taking different forms of artistic action, often through lines of enquiry that have met with official resistance. By interrogating the residual body of evidence of enduring Aboriginal occupation in postcolonial collection-building and record-keeping, Watson returns agency to its subjects and objects.

In recovering history from place and, indeed, reinfusing it back into place, Watson has made several significant public art projects around Australia, including at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA). Commissioned to mark GOMA’s tenth anniversary, the monumentally scaled bronze net sculpture, tow row 2016 (illustrated), is emblematic of ancient fishing technology of the kind once deployed along the coastlines and waterways of south-east Queensland. Its design was based on early photographs of the butterfly-shaped nets Watson observed in Maningrida, Arnhem Land, and one from Doomadgee, close to Waanyi Country, held in the State Library of Queensland. tow row‘s complex netting weave was created in collaboration with Ngugi artist Elisa Jane Carmichael, and the work typifies Watson’s longstanding practice of engaging the assistance of young First Nations artists in the making of her work. For all its strength of purpose, there is a common thread of humility that courses through Watson’s art in the mode of its production, and even in the lower-case typography of its naming.

Viewing original fishing nets referenced in ‘tow row’ 2016

Judy Watson ‘tow row’ 2016

Watch | Judy Watson introduces ‘tow row’ 2016

Judy Watson, Waanyi people, Australia b.1959 / Judy Watson with tow row 2016 / Bronze / 193 x 175 x 300cm (approx.) / Commissioned 2016 to mark the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art. This project has been realised with generous support from the Queensland Government, the Neilson Foundation and Cathryn Mittelheuser AM, through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Judy Watson/Copyright Agency

Watch | Shadow time-lapse

Watch how Judy Watson’s ‘tow row’ 2016 interacts with the Queensland sun creating a shadow that extends the sculpture’s footprint outside GOMA’s entrance.

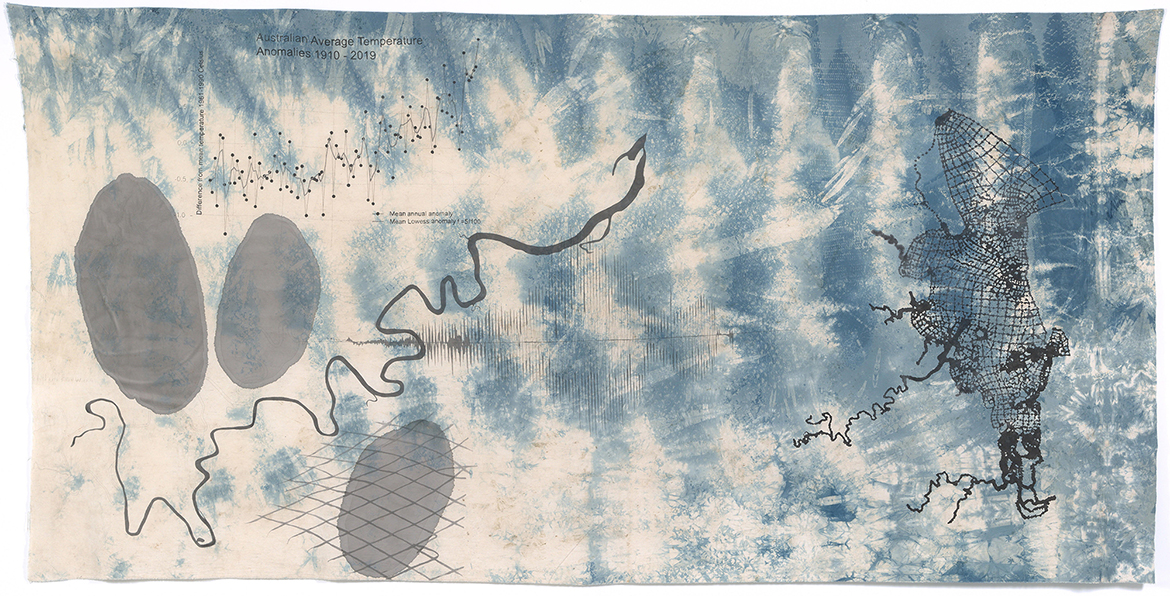

‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri: Judy Watson’ is shown across the Queensland Art Gallery’s central exhibition spaces, including its Watermall. It features a major new acquisition, moreton bay rivers, australian temperature chart, freshwater mussels, net, spectrogram 2022 (illustrated), which faces walama 2000 (illustrated), a selection of inverted bronze termite mound and dillybag sculptures that appear to drift over the water’s surface.

Judy Watson ‘walama’ 2000

Judy Watson ‘moreton bay rivers, australian temperature chart, freshwater mussels, net, spectrogram’ 2022

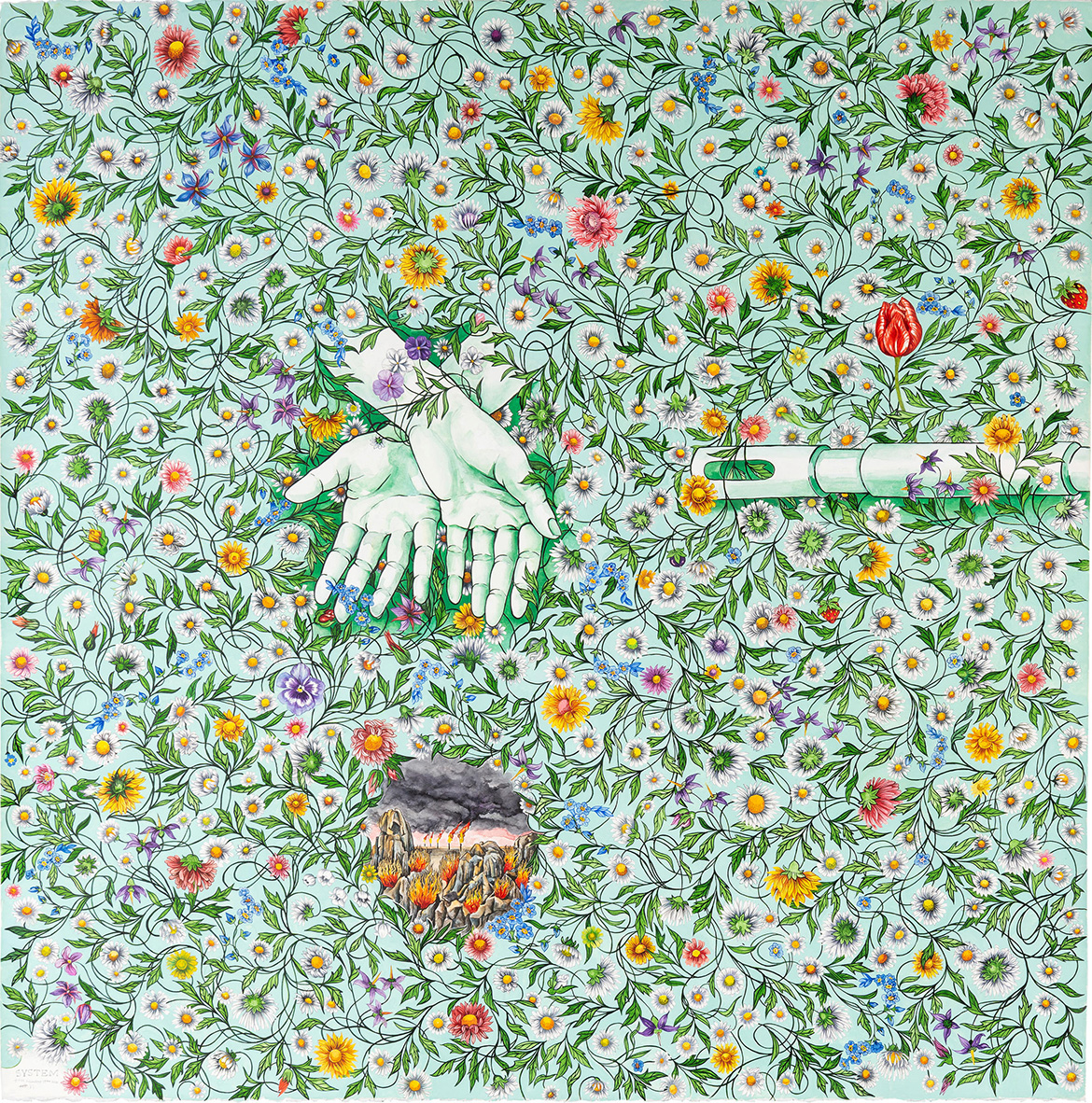

At the exhibition’s core are Watson’s large unstretched canvases, impressively and seductively charged with pigment and pastel or, nature print–like, carrying an impressed rubbing of what lies beneath. These works have been a mainstay of Watson’s oeuvre since the late 1980s. They are pressed with intense fields of ochre, ultramarine and sanguine pigments that speak of land and sea, tracing human occupation through the evidence of its skin and blood, somehow mapping the emotional and psychological states to which this ancient land has borne witness.

Judy Watson ‘grandmother’s song’ 2007

Of her Country, Judy Watson once said, ‘I listen and hear those words a hundred years away. That is my Grandmother’s Mother’s Country, it seeps down through blood and memory and soaks into the ground.’2 Drawn out of the past, the sorrowful beauty of these works is simply part of their insistent search for enlightenment. ‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri’ — ‘tomorrow the tree grows stronger’ — offers us an elegiac message of hope for the future.

Judy Watson has talked about her Waanyi people being known as ‘running water people’, for the dynamic nature of the water in their Country.3 It is a quality that equally applies to her restless, searching practice.

QAGOMA is pleased to present this exhibition that honours the work of one of Queensland’s and Australia’s most significant visual artists.

Chris Saines CNZM is Director, QAGOMA

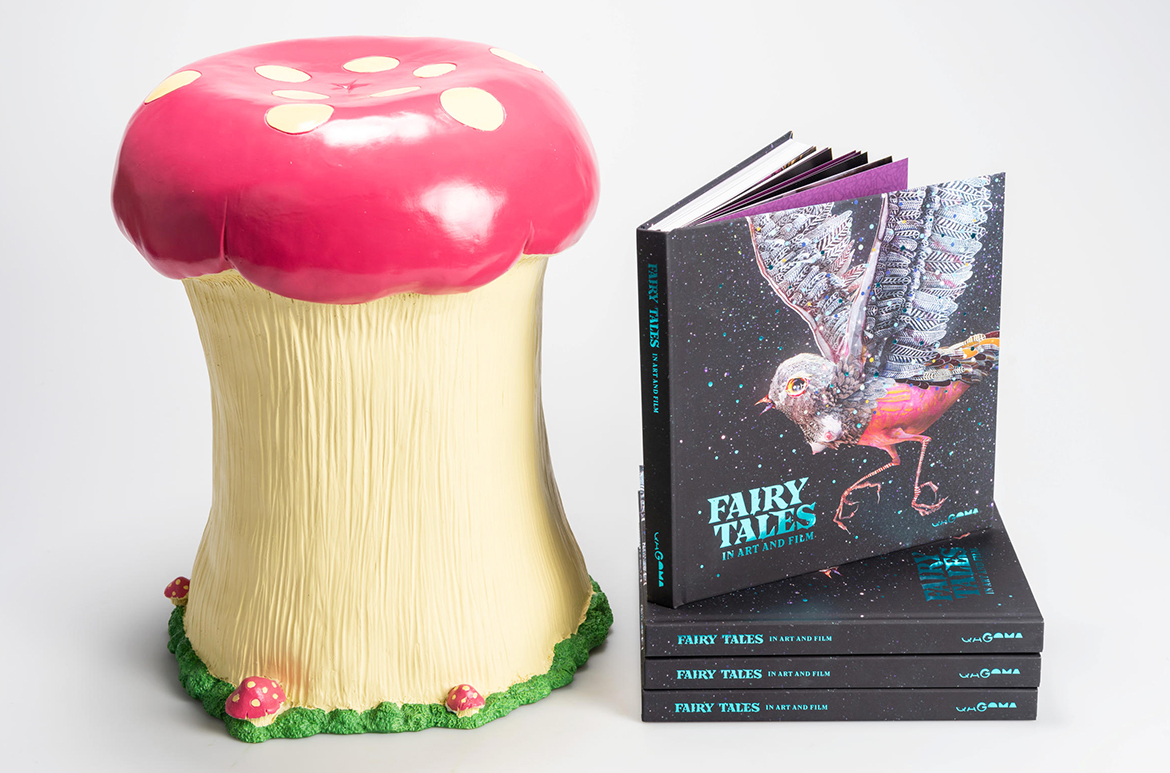

This edited extract was originally published in the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art exhibition publication mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri: Judy Watson available at the QAGOMA Stores and online.

Endnotes

1 Hetti Perkins, ‘Judy Watson’, The First Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1993, p.110.

2 Judy Watson, artist statement, Wiyana/Perisferia (Periphery) [exhibition catalogue], Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative at The Performance Space, Sydney, 1992.

3 Judy Watson, artist statement, National Indigenous Art Triennial: Culture Warriors [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p.167

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country. It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are respectfully advised that this exhibition contains images of ancestors, now deceased, and references to strong themes of colonial frontier violence.

Featured image: Judy Watson, Waanyi people, Australia b.1959 / walama 2000, installed in ‘mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri: Judy Watson’, Queensland Art Gallery (QAG), Brisbane 2014 / Bronze / 17 parts (height x diam.): Part A: 159 x 60cm; part B: 151 x 55cm; part C: 155 x 60cm; part D: 120 x 50cm; part E: 115 x 44cm; part F: 119 x 46cm; part G: 99 x 48cm; part H: 120 x 58cm; part I: 131 x 60cm; part J: 120 x 58cm; part K: 131 x 60cm; part L: 90 x 30cm; part M: 105 x 30cm; part N: 90 x 40cm; part O: 100 x 40cm; part P: 40 x 20cm; part Q: 35 x 20cm / Courtesy: The artist, Milani Gallery and UAP Brisbane (Meeanjin/Magandjin) / © Judy Watson / Photograph: N Umek © QAGOMA

#QAGOMA