The Australian Cinémathèque begins a two-part retrospective of works by Rainer Werner Fassbinder. His films were provocative during his lifetime, and his stories continue to resonate with contemporary audiences.

I’d like to be for cinema what Shakespeare was for theatre, Marx for politics and Freud for psychology: someone after whom nothing is as it used to be.1

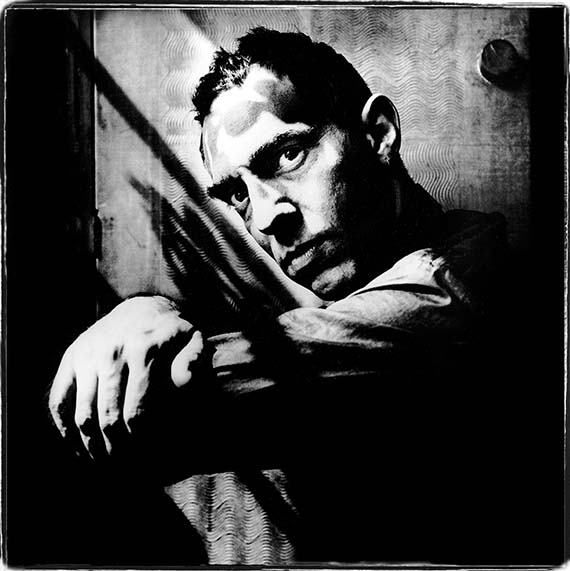

During his short and self-destructive life (he died of a drug overdose at 37), Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945–82) worked at a frenzied pace and fashioned a practice that was both mercurial and brutally honest. Between 1966 and 1982, he directed an astonishing 39 films (including six television movies and series) and four video productions. He directed 24 stage plays, four radio plays, and worked as an actor, dramatist, cameraman, composer, designer, editor, producer and theatre manager. He famously claimed, ‘I don’t throw bombs; I make films’, and cherished his position as one of the most polarising and influential figures of New German Cinema.2

Fassbinder

Fassbinder has been described as many things: prodigious to the point of folly; a homosexual who loved men and women equally; an unashamed exhibitionist; a tyrant in the workplace; and a radical, no matter your political persuasion. Born to a middle-class family in Bavaria, Fassbinder was quick to denounce the propriety of then-West German society, which he felt impeded his personal freedoms. He began his career with Munich’s Action-Theater ensemble, amid the disillusionment that followed the failed protests of May 1968, and there he wrote and directed a series of plays that he would later adapt for the screen. Without a formal university education, Fassbinder worked tirelessly to prove himself and to create works that would expose the foolishness and hypocrisy he saw in human relationships. He reasoned:

I detest the idea . . . that the love between two persons can lead to salvation. All my life I have fought against this oppressive type of relationship. Instead, I believe in searching for a kind of love that somehow involves all of mankind . . .3

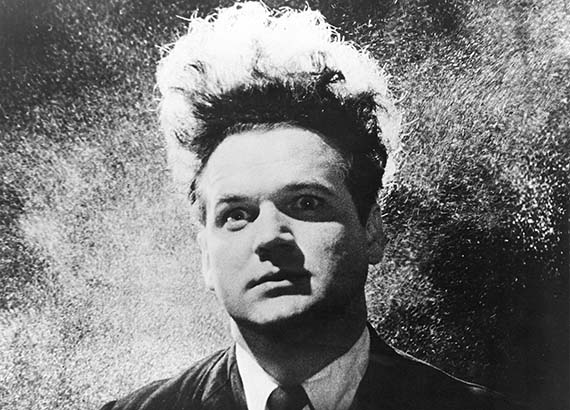

Love is Colder than Death

Fear Eats the Soul

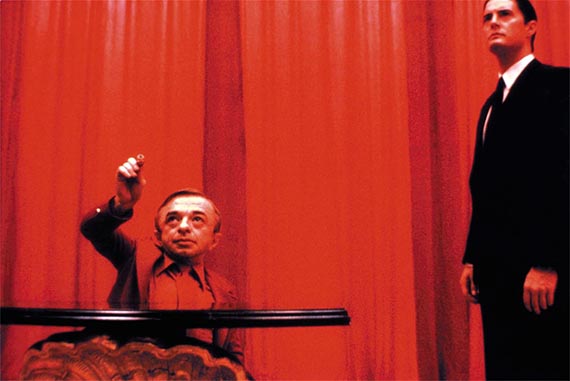

Fassbinder favoured an aesthetic eclecticism that allowed him to experiment with contradictory genres, styles and cultural references — from social melodramas and comedies to science fiction and thrillers, psychological dramas and austere literary adaptations. His early films drew inspiration from the gangster films of the French New Wave and the methodologies of Bertolt Brecht and Antonin Artaud. During the 1970s, he was heavily influenced by the technicolour melodramas of Hollywood director Douglas Sirk. They imbued the mise en scène of his later works with lurid colours, artifice and plenty of histrionics, yet his use of melodrama was never for the sake of sarcasm: ‘I don’t believe that melodramatic feelings are laughable — they should be taken absolutely seriously’.4

For Fassbinder, there were no taboo subjects in cinema, just taboo means of representing them and his films often deal with challenging subjects, including the terrorism of the Baader- Meinhof group and the politics of postwar Germany; the alienated experiences of women and homosexuals; as well as the plight of migrants, interracial couples and the socially downtrodden. The key trajectory through these stories is the interplay of cruelty, exploitation and victimhood, where distinctions between the oppressed and the oppressors are not clear or simple. For Fassbinder, the reworking and remaking of this thematic was the very basis of his practice:

Every decent director has only one subject, and finally only makes the same film over and over again. My subject is the exploitability of feelings, whoever might be the one exploiting them. It never ends. It’s a permanent theme. Whether the state exploits patriotism, or whether in a couple relationship, one partner destroys the other.5

Berlin Alexanderplatz

Alfred Döblin’s celebrated Weimar Republic novel Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929) was a major influence for Fassbinder, which he later adapted into a cult television series. He argued that reading the text as an adolescent had enabled him to avoid becoming ‘completely and utterly sick, dishonest and desperate’ like other Germans.6 Further literary adaptions include Vladimir Nabokov’s Despair (1934), about a man who undertakes the perfect crime — his own murder; Theodor Fontane’s realist novel Effi Briest (1894), about a woman trapped by marriage and social conventions; and Jean Genet’s Querelle of Brest (1947), which evoked an erotic underworld of sailors and hustlers. In these texts, Fassbinder found exiles, outcasts and strangers — characters that inhabited a world filled with prejudice and injustice. Never one to be overly sentimental, Fassbinder allowed these characters to be openly troubled as a way of confronting audiences with their fears — a fear of others and a fear of the self.

Fassbinder maintained an intense working relationship with a recurring cast of actors and technicians, which often spilt over into dysfunctional and intimate relations off set. As actor Harry Baer recalls, ‘It was totally insane. We didn’t need any speed in those days. All we needed was a dose of Fassbinder’.7 He was accused of treating those around him as marionettes, and his combative personality and directorial style caused him to be estranged from some of his principal collaborators. Yet this group formed something of a surrogate family, and it is this working process that fed Fassbinder’s relentless drive and output. His films bear a signature style and continuity through the work of cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, production designer Kurt Rabb, editor Juliane Lorenz, musician Peer Raben, and the luminous presence of stars, like Hanna Schygulla and Irm Hermann, who appear throughout Fassbinder’s filmography.

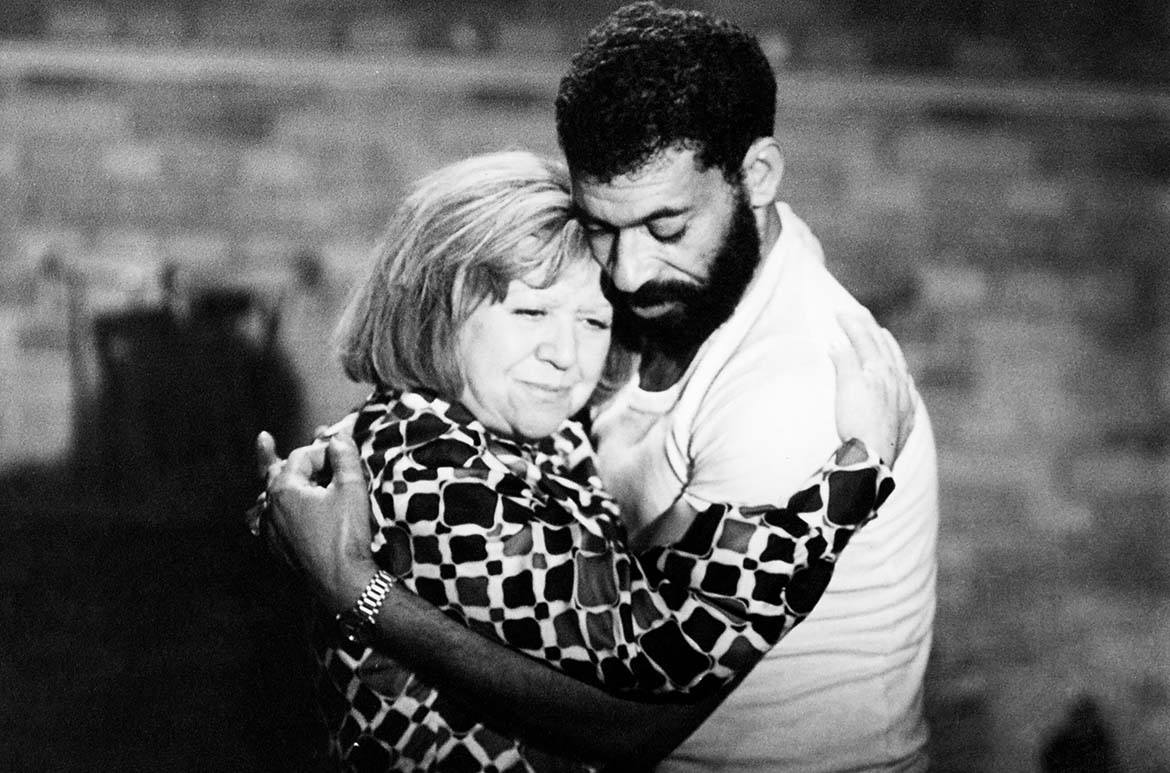

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant

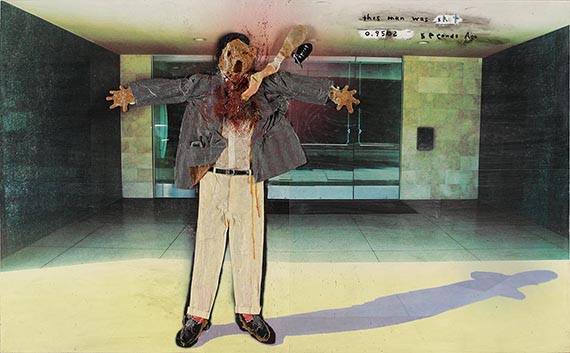

World on a Wire

Along with greater access to his work through film restorations, there is currently a resurgence of interest in Fassbinder’s seminal theatre works and film retrospectives. His oeuvre has inspired generations of contemporary artists, including Ming Wong, Runa Islam, Rikrit Tiravanija, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and filmmakers such as Pedro Almodóvar, Todd Haynes and Christoph Schlingensief.

While Fassbinder never lived to see German society change after the country’s reunification in 1990, the social conditions he railed against persist today. As a conservative political establishment sweeps across Western Europe, it’s unsurprising that his works are being reconsidered and championed by new audiences.

Endnotes

1 This quote is widely attributed to Fassbinder.

2 Fassbinder’s proclamation on the film poster for Die Dritte Generation (The Third Generation) 1979. The ‘New German Cinema’ was a pledge by filmmakers during the late 1960s and 70s to create challenging works for postwar Germany. Alongside Fassbinder, this disparate group included directors such as Margarethe von Trotta, Volker Schlöndorff, Wim Wenders, Werner Herzog, Alexander Kluge and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg.

3 Fassbinder discussing George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) in Robert Katz and Peter Berling’s Love is Colder than Death: The Life and Times of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jonathan Cape, London, 1987, p.166.

4 Fassbinder, cited in Wallace Steadman Watson, Understanding Rainer Werner Fassbinder: Film as Private and Public Art, University of South Carolina Press, 1996, p.107.

5 Fassbinder, cited in Thomas Elsaesser, Fassbinder’s Germany: History, Identity, Subject, Amsterdam University Press, Holland, 1996, p.352.

6 Fassbinder cited in Wallace Steadman Watson, p.234.

7 Harry Baer, cited in Michael Koresky, ‘Early Fassbinder’, Eclipse Series 39: Early Fassbinder, The Criterion Collection, 2013.

Curious to know WHAT ELSE IS screening at the australian Cinémathèque?

José Da Silva is Curatorial Manager, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

Feature image: Production still from Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant (The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant) 1972