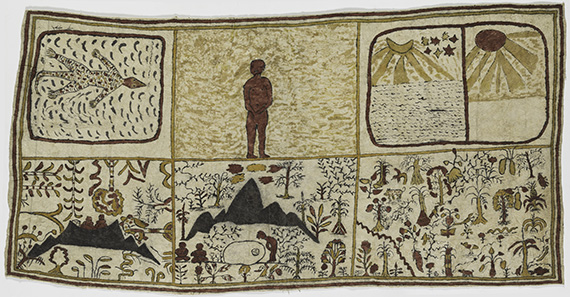

Created by the only male Ömie barkcloth painter, this detailed visual creation story, recently acquired by the Gallery, marks a significant departure for the Ömie people of Papua New Guinea.

In 2009, 63-year-old law man Rex Warrimou began the process of recounting the Papua New Guinean Ömie people’s creation story to young Australian curator Brennan King. The story, entrusted for centuries to select men of the tribe, was slowly recorded, first as an oral history and more recently as a series of nine paintings on barkcloth. Without local precedent, these narrative paintings resonate with the enormity of what the artists are attempting to capture. The composition of each painting follows the logic of a story told, weaving together bold treatments of space, tone and theme with intimate detail.

Warrimou’s choice of barkcloth as the canvas for this recording reflects two things: the role of barkcloth in the creation story, and the importance of this medium to the contemporary survival of the Ömie people. Residing high on the slopes of volcanic mountains in Oro Province, the Ömie territory is extremely remote and without agricultural or mineral resources to propel them into a global economy, and yet today, as the result of a growing international appreciation of the Ömie women’s stunning abstract barkcloth paintings, this remote tribe is one of the more well-known and self-sufficient in the country. Found in major museum collections throughout world, Ömie women’s barkcloths record connections to specific locales and stories as well as translating the spiritual experience of these places and their history. While poetic stories are often recounted in the works, bold abstract motifs conceal as much as they reveal. This is partly because individual women are given access to only specific parts of the Ömie story. The name of the first woman to make the cloth was Suja, which translates as ‘I don’t know’.

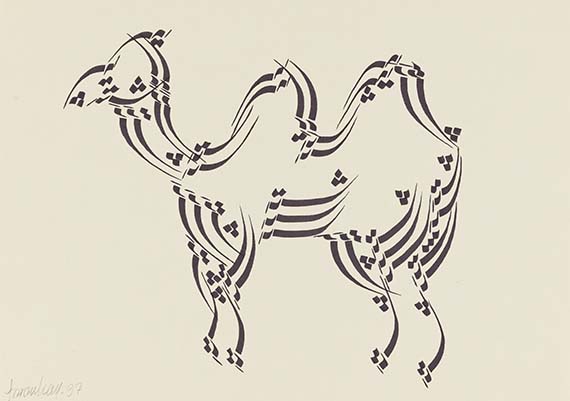

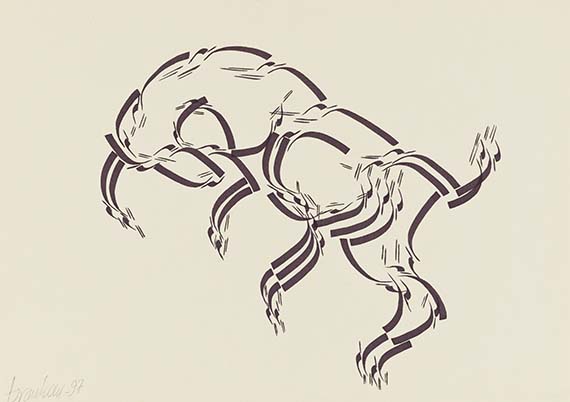

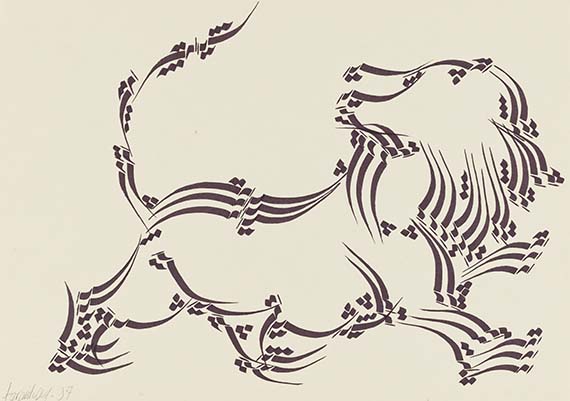

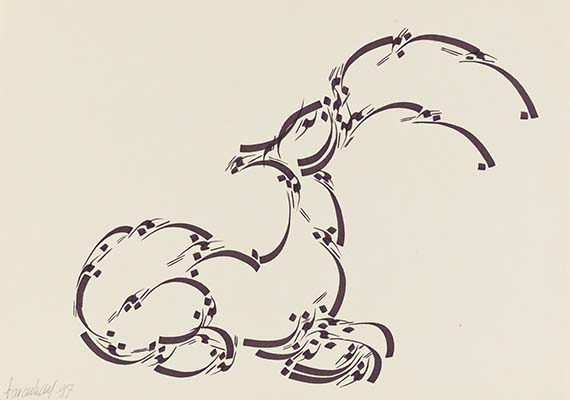

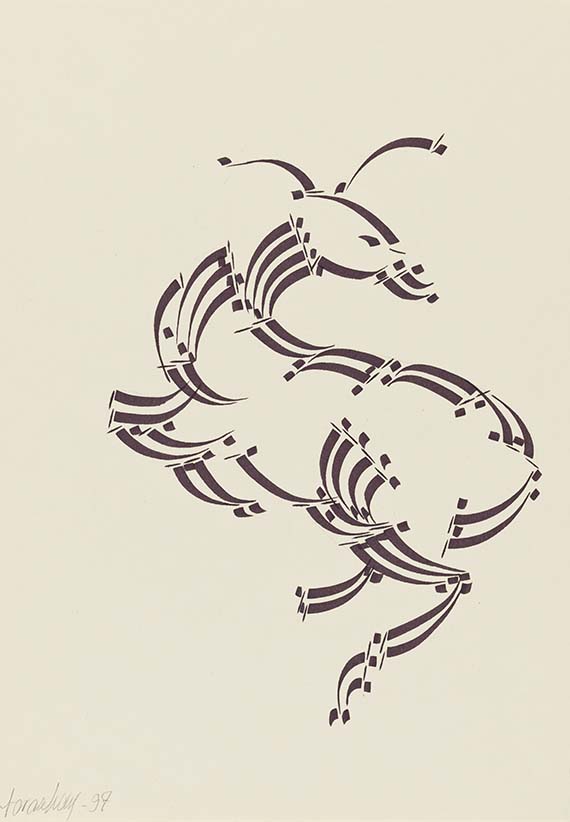

This artwork is the last in Warrimou’s series. It is also the most complex and ambitious, illustrating a continuous thread from the creation of the world by Uhöeggö’e the lizard through to its population with plants, animals, insects, birds, the seasons, fire and humans.

In Warrimou’s own words:

Uhöeggö’e was at the lake and created everything from its water — the trees, plants, animals, insects, birds, wind, storms, stones, fire and fruits and vegetables for food. He saw the world he had created was very beautiful but that there was no one to look after it.

Uhöeggö’e watched as the water in the lake tried to create human beings. But the water was making many mistakes — the humans did not look like proper humans. Uhöeggö’e looked into the lake and saw himself reflected in its surface like a mirror and thought to himself, ‘I am going to create a man in my own image’. He drew his own image in the ground and with his hands he then helped the water mould the first man, Mina, and said, ‘Now you will become a man’.1

Created by the only male Ömie barkcloth painter, Warrimou’s Our Creation (Ömie) marks a significant departure in the history of the tribe, for the first time visually recording a story safely ‘kept’ by its senior men. The work is alive with the generosity and openness of this gesture, one that expands not only our understanding of the exquisite abstracted paintings of Ömie women but also of their culture and home.

Endnote

1 An excerpt from Rex Warrimou (Sabiö), ‘Ömie Creation’, in Jiji Dor’e Dahor’e (Star on the Mountain) [exhibition catalogue], Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane, 2015. Full text emailed to the author, May 2015.