Secular, fluid and simple in form, classic fairy tales involve characters defined by their social roles (woodcutter, stepmother, queen) or appearance (‘Little Red Riding Hood’, ‘Snow White’, ‘Beauty, the Beast’). These foundations provide a scaffold for storytellers to adapt the tales for their own audiences.

The term ‘fairy tale’ comes from the French phrase conte de fées, from the writings of seventeenth-century author Marie Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Comtesse d’Aulnoy. The Comtesse coined the term to describe the inventive magical tales she told to entertain visitors to her Paris salon. Previously shared orally by the working class, several of these stories were subsequently reimagined and written down by the aristocracy, who used the themes of enchantment to mask critiques of the grandeur, excess and politics of the French court. These conte de fées also communicated real-world advice about marriage and family.

Contemporary artists, designers and filmmakers use tales such as ‘Cinderella’, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and ‘Snow White’ to explore the power structures of wealth and status that serve as both obstacle and aspiration. Contemporary retellings connect with audiences through character types — nobility, wicked (step)mothers and witches, tricksters and lost children — alongside the enduring visual cues of magic mirrors, poisoned apples, glass coffins, blood, carriages, castles and witches’ houses. Contemporary artists also subvert fairy-tale conventions to discuss prejudice, injustice and the class divide.

‘Fairy Tales’ unfolds across three themed chapters. ‘Into the Woods’ explores the conventions and characters of traditional fairy tales alongside their contemporary retellings. ‘Through the Looking Glass’ presents newer tales of parallel worlds that are filled with unexpected ideas and paths. ‘Ever After’ brings together classic and current tales to celebrate aspirations, challenge convention and forge new directions.

Travel with us in our weekly series through each room and theme of the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) as we introduce you to some of the works.

DELVE DEEPER: Journey through the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition with our weekly series

EXHIBITION THEME: 2 Into the Woods

Gustave Doré ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ 1862

Created in 1862, Gustave Doré’s captivating painting Little Red Riding Hood (illustrated) was made originally as a wood-engraving for the fairy-tale publication Les Contes de Perrault (The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault), printed in 1697. Doré embraced the dramatic tension of Perrault’s original tale, depicting a young girl and the wolf, dressed in Grandma’s cap and nightgown, both beneath the bedcovers in the moment before he devours her.

French aristocrat and author Charles Perrault tells the story of a young girl who meets a cunning wolf on the way to visit her ailing grandmother in the woods. Perrault wrote the story as a warning to young women tempted to stray from the safety of the path — a metaphor for the dangers of speaking to strange men in private. According to Perrault, Little Red Riding Hood’s grisly death in his version is her own fault; naive girls should know better than to associate with beasts. A later version by German folklorists the Brothers Grimm (Little Red Cap, written in 1857) offers a kinder ending, in which a huntsman appears in time to kill the wolf and save both grandmother and grandchild.

Urs Fischer ‘A–Z’ 2019

Colour plays an important role in fairy tales, as does food. In the classic Brothers Grimm’s telling of ‘Snow White’, it is the redness of the apple that lures Snow White to reach for the poisoned fruit offered to her by her vengeful stepmother, the queen. In the visual language underpinning many fairy tales, the colour red implies bloodlines, sexuality and life force; while Snow White’s consumption of the poisoned fruit’s uncanny white flesh (a colour suggesting life, light and fertility) indicates her impending transformation to a death-like state.

Urs Fischer’s hyperrealist sculpture A–Z 2019 (illustrated) is a beautiful depiction of a half-eaten apple and pear, with its realistic appearance raising questions about life, death and decay. Just as Snow White, lying motionless in the story’s glass coffin, is neither dead nor alive, Fischer’s life-like fruit, created in bronze, is strangely arrested in time. It is a nod to a way of painting still life in the seventeenth-century, which explored ideas of life and death.

Jana Sterbak ‘Inside’ 1990/2023

‘Snow White’, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and similar tales such as the Brothers Grimm’s ‘The Glass Coffin’, explore the idea of death-like slumber — where the character is unable to be awoken by regular means. Often the result of a magic spell or potion, these characters remain in this inert state until a trick of fate (Snow White’s glass coffin is moved, which dislodges the piece of poisoned apple from her throat) or by design (Sleeping Beauty is awoken by a prince’s kiss).

This idea of deep slumber is explored by Jana Sterbak in her sculpture Inside 1990/2023 (illustrated) — a rendering of a life-sized glass coffin, with a smaller, mirrored coffin inside. The work considers these stories and the lifeless young women they often depict, evoking questions of identity, materiality, vulnerability and control. Drawn into a deep slumber and rendered doll‑like, they become objects of desire and fascination, their repose visible through the glass of the coffin. Inside masterfully looks at the implications of this: by incorporating a mirrored coffin within, one that reflects back the faces of those viewing, we are drawn into a conversation about voyeurism and fate.

Eiko Ishioka (Designer) ‘Yellow dress with hood’ costume

Watch | Director Tarsem Singh’s filmic adaptation of ‘Snow White’

Courtesy: Relativity Media

Watch | Go behind-the-scences of Eiko Ishioka’s costumes

Courtesy: Relativity Media

Showcased in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition are eight incredible creations by Eiko Ishioka, created for Mirror Mirror — director Tarsem Singh’s filmic adaptation of ‘Snow White’. Richly detailed and sumptuously executed, Ishioka’s costumes bring the impossible luxury of fairy tales to life.

Three costumes for the character Princess Snow worn by Lily Collins stand in contrast to the luxuriant designs for Queen Clementianna worn by Julia Roberts. Softer and less ridged in construction, the first ‘Yellow dress with hood’ costume (illustrated) — encountered in the exhibition’s ‘Into the Woods’ section — combines pastel pink, green and yellow, with embroidered flowers and butterflies to signal youth and innocence.

Ishioka described her concept for Mirror Mirror as ‘hybrid classic’, an approach that allowed the designer to draw on fashions from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries to create the grandeur and whimsy of the fairy tale aesthetic sought by director Tarsem Singh. Ishioka led the creation of more than 400 costumes, as well as the purchase of and alterations to an additional 600 existing costumes. While many were completed by local costumiers and craftsman in Montreal, close to her studio and the film’s shooting location, the primary costumes were handmade in New York across four different ateliers; Tricorne Costumes, Jennifer Love Costumes, Carelli Costumes and Eric Winterling Costumes.

The ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition is at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Australia from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

‘Fairy Tales Cinema: Truth, Power and Enchantment‘ presented in conjunction with GOMA’s blockbuster summer exhibition screens at the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

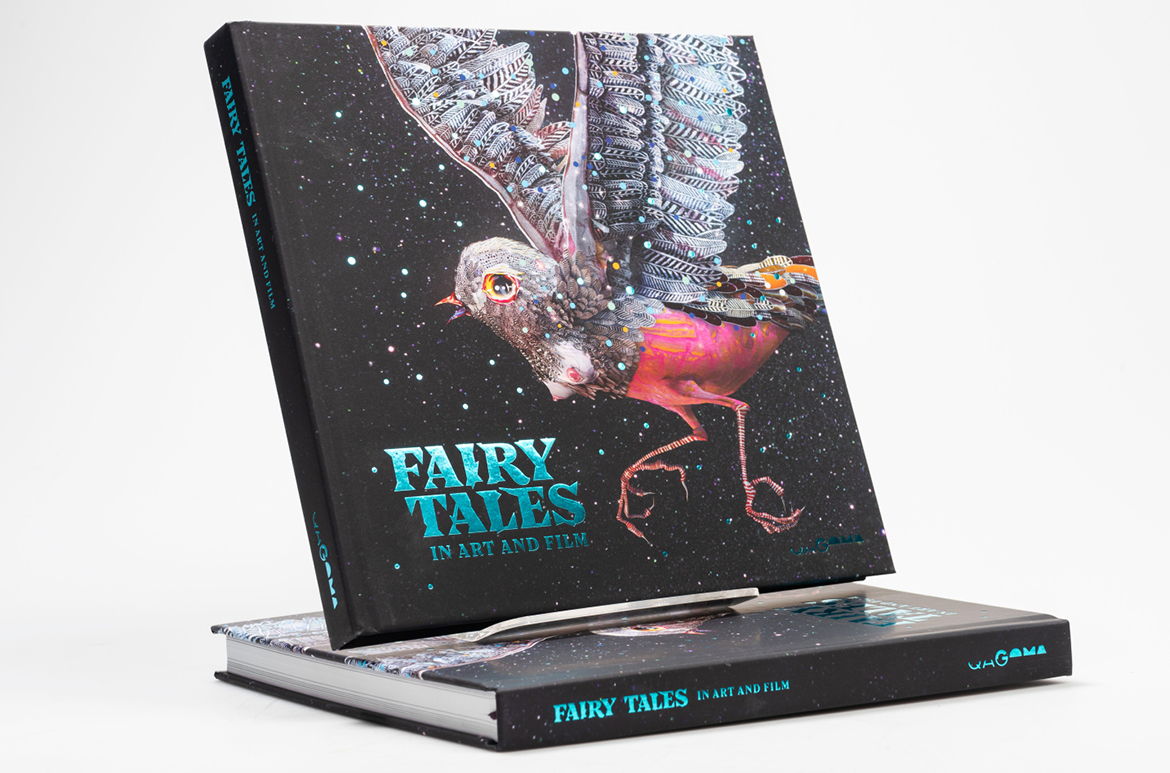

The major publication ‘Fairy Tales in Art and Film‘ available at the QAGOMA Store and online explores how fairy tales have held our fascination for centuries through art and culture.

Featured image: Jana Sterbak Inside 1990/2023, installation view ‘Fairy Tales’, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) Brisbane 2023

#QAGOMA