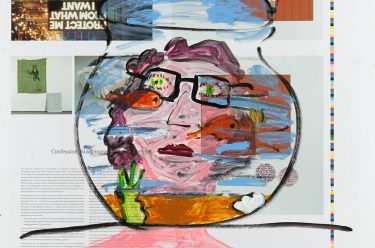

In the garden of good and evil is Brisbane artist Judith Wright’s most recent work in an ongoing project that aims to construct the imagined life of a lost child. Here, the artist gives some personal insights into the many elements of this moody multimedia installation, which ultimately tells of the resilience of memory and life.

The garden continues my reflections on vulnerability, love and loss. Though the works are inevitably touched with melancholy, there is often an element of the sanguine. For many years, I have returned to the idea of a lost child.

While this installation is presented in 2018, its many elements started back in 2003. The present installation is, in a sense then, a memorial piece to this lost child. We all experience loss at some point in our lives, as we do love. This duality is expressed throughout the work — light/shadow, body/spirit, love/loss. It seems impossible to experience one without the other.

With that loss held in the hearts and minds of those who loved them, I have sought to create a timeless garden replete with strange creatures and birds, some created from the offcuts of the sheltering ‘family trees’. My characters wander and play in this imaginary space. The idea that this play might be accompanied by music made real sense to me, and contemporary composer Liza Lim has enriched the installation with a sound piece. Together with the theatrical lighting, the sense of foreboding, the dramatic impact, is increased.

My former career as a ballet dancer has perhaps been influential in my work. Dancers on a stage are acutely aware of space and the special relationships between one’s own body and those of the other dances. Clearly, the capacity of the body to convey emotion is central to this performance. Sir Robert Helpmann was director of the Australia Ballet when I was in the company. He was a master of stagecraft, and working with him was an inspiration for many young dancers. The choreographic team, Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon, fellow dancers of the time, with whom I have since worked on one of my videos, would, I know, concur with this. We have a future project in mind!

I enjoy working across various media using painting, sculpture, video and performance. I have long been fascinated by the Greek philosopher Plato who recounted how the shadows cast on a cave wall prompted humans to first represent themselves; and indeed by Roman historian Pliny the Elder, who recounted how Kora of Sicyon traced her lover’s shadow on a wall to preserve his memory. Her father, Butades, the first ancient Greek clay modeller, used his daughter’s drawing to create a clay model of the youth’s face.

The notion of shadows is a key feature in The garden, with the work being articulated not by drawing but by cast light. Roughly handcrafted wooden forms cast their silhouettes across the tall white walls of the gallery. The play of light animates so that they dance amidst the dark pooling and sharp reliefs. As shadows they express both presence and absence in the same moment. Again these dualities emerge — form and shadow, strength and vulnerability, appearance and disappearance.

I have always used my body to define the scale of my work. The large works on paper that I have made time and again measure my full reach. My choice of life size figures — the mannequins that become the actors in this drama. Their scale and that of the large paintings are determined so that our engagement with them is human. My dolls create a tension between the living body and the inanimate object — of life and death forces. As the body is an instrument of the dancer’s craft — similarly for me, now, my artistic decisions remain filtered through this constant.

As technology moves us further away from our physical bodies, a consideration of the role of the senses seems timely. This shift surely leads us back to materiality, to tactility — the feel of a surface — skin, hair, wood, paper. Without the ability to touch, loss becomes absolute. An awareness of touch and sight dictates my chosen materials. They always carry earlier histories and traces of their other lives and I love gathering their disparate parts and assembling a new, reconstructed self.

I have worked for many years now on creating installations — each one continues my meditation on the fragility of the human condition. Awake 2012 celebrates a life. A Journey, from the same year, propels its characters forward on a journey through the underworld to their Destination (2013), where the protagonists experience an alternate world or state of existence. From there comes The Ancestors 2014, in which these lives are maintained, for a time, in the minds and hearts of those who loved them. Finally, In the garden of good and evil 2015–18, we take a further step into the world of the imagination. It is a space in which characters can frolic and play, a space for revelry, with perhaps just a hint of a nightmare.

Judith Wright is a Brisbane artist who works across a range of media including painting, drawing, video, sculpture and installation

Subscribe to YouTube to go behind-the-scenes / Read more about your Australian Collection

Stay Connected: Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog

Feature image: Judith Wright with her work In the garden of good and evil 2015–18 / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA

#JudithWright #QAGOMA