This collection of extraordinary telia rumal (some of which are on display within the exhibition ‘I Can Spin Skies’ at the Queensland Art Gallery’s Henry and Amanda Bartlett Galleries (5 & 6) was made using time-consuming double ikat dyeing techniques. Few weavers still maintain the skills required to create these attractive textiles, in part because economic pressure demands faster production.

Dana McCown, textile specialist on the telia rumal tradition, and who recently gifted this collection to QAGOMA gives us an insight into their craftsmanship and beauty.

Gajam Ramulu ‘Telia rumal’ 1999

Gunti Bhaskar Rao ‘Telia rumal with Islamic designs’ c.1990s

Nalgonda Weaver ‘Telia rumal with lions, clocks and swastikas’ c.1990s

The origins of telia rumal

The name telia rumal is derived from the oil process that enables the cotton fibre to accept dye. Telia means oil and rumal means square, referring to the basic shape of the textile. The style developed in Chirala, on the coast of Andra Pradesh, with the earliest recorded pieces made in the 1800s, but spread further to the Nalgonda District due to high demand from Arabic markets. Presently, the village of Puttapaka, Nalgonda District is one of the few places still weaving the telia rumal. There, the Gajam family have been keeping the skill alive.

Traditionally the imagery of the telia rumal was simple and geometric, but over time both Arabic and Hindu imagery was introduced. In the 1920s, more modern images emerged, from airplanes to clocks.

The Puttapaka weavers carrying on the tradition are from the Padmasali caste, which, translated, means ‘lotus weavers’. Life in the village centres around the temple; within, a family tree on the wall depicts the god Markandeye at the apex, with all Padmasali weavers descending from his sons.

The ikat process

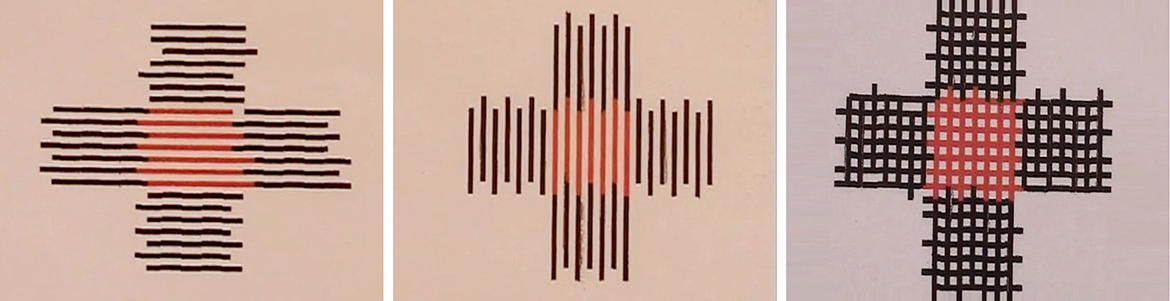

The more common single form of ikat is a process where the warp or weft yarn is resist-tied before being dyed and then woven. (‘Resist dying’ uses various methods — in this case, tied-off sections of yarn — to dye textiles with patterns.) Single ikat is found in many places around the world, but double ikat is more rare, requiring a high degree of work and precision found in only a few places, particularly in Japan, India and Bali.

There is a simple way to distinguish if fabric is ikat: the edges of images have a ‘feathering’ effect, created as the yarn moves slightly while weaving. If the feathering is on the right and left sides of the image, then it is weft ikat; if on the top and bottom, it is warp ikat. Feathering on all edges of shapes and images indicates double ikat.

To make telia rumal imagery, the weaving process requires an even greater degree of precision and preparation than for single ikat. To create the tied resist (undyed) areas on the yarn, the warp is first taken outside and stretched to full length. Rumals are traditionally made in units of eight. After stretching the yarn, a folding process enables all eight pieces to be tied at once, thus saving considerable time. The large areas to be resisted are tied with black rubber strips from bicycle inner tubes. These are easily available in the village, as many villagers ride bikes. Small resist areas are done with cotton yarn.

The weft yarn is also tied in bundles depending on how complex the design is. The simple design in this weft yarn — seen stretched out below on a frame for tying — has only 15 bundles to be tied differently. More complex designs could have 150 bundles all tied and dyed differently. The first colour is always red; after that dye bath, ties are removed and re-tied to protect red and white areas from the black dye.

How telia rumal fabric is used

Traditionally, telia rumal has been worn in various ways by both men and women. Here are contemporary examples of it being worn both as turban and shoulder cloth for men.

During the rule of the Nizams (1724–1948), telia rumal was popular with aristocratic Muslim women of Hyderabad. They wore two (square) rumal lengths joined together as dupattas or shoulder cloths. Eventually these dupattas were specially woven as rectangles, without the border between the two squares. Occasionally, they were heavily embroidered around the edges using gold, silver or silk thread to create a luxurious textile.

The contemporary telia rumal shawl/dupatta (illustrated below), hand-embroidered with silk thread in a paisley motif with trailing flowers, was commissioned by late textile enthusiast, Mrs Suraiya Hasan of Hyderabad. She searched for weavers and embroiderers able to replicate old styles seen in museum photographs.

Today, telia rumals are recognised for their craftsmanship and beauty, and are also created for decorative purposes. The large award-winning piece pictured below — designed and woven by Master Weaver Gajam Govardhan of Puttapaka — contains 100 different images of significance. Because there are no repeated images, the work required to resist-tie the yarn took months. Hundreds of bundles were individually tied and died for warp and weft. It is considered his ‘masterpiece’. For this extraordinary accomplishment, he was awarded the Padma Shri Award — the fourth-highest civilian award for distinguished service in India.

Weaving the telia rumal in South India

Two groups of the telia rumal gifted to the QAGOMA Collection have been featured ‘I Can Spin Skies’ in Queensland Art Gallery’s Henry and Amanda Bartlett Galleries (Galleries 5 and 6) between August 2023 and June 2024.

Dana McCown is a textile specialist world-renowned for her research on the telia rumal tradition. Her expertise is captured in a remarkable collection of textiles, gifted to the Gallery in 2020, which she worked closely with artists to develop over the course of more than 25 years. A selection of these works was included in ‘An Endangered Species: Telia Rumal: Double Ikats of South India’, exhibited at Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery in 2001, for which McCown wrote the accompanying publication.

Featured image: Gajam Govardhan’s award-winning 100 motif telia rumal 2011, installed for the first rotation of ‘I Can Spin Skies’, QAG, Nov 2023 / Gift of Dana McCown through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation 2020 / © QAGOMA / Photograph: J Ruckli © QAGOMA

#QAGOMA

Wonderful article!! Thanks for sharing this amazing process!