European jewellery of the Renaissance was colourful, opulent and intricate. It was also widely popular, as the portraiture of this time shows the often extraordinary amount a wealthy man or woman might wear.

Many great artists of the Renaissance started their careers in goldsmiths workshops — resulting in a familiarity of styles and techniques in the detailed depiction of jewellery in portraits of this time. These depictions provide valuable insight for us today into what was produced — given that few pieces of the time have survived.

The youth wears a very long chain of gold bars connected with shorter sections of oval gold links to suspend a large gold medallion. Although we can’t see the design on this medallion it might likely be of a classical and mythological content, such themes provided the link with the ancient world so central to Renaissance art.

LIST OF WORKS: Discover the artworks

DELVE DEEPER: More about the exhibition

THE STUDIO: Artworks come to life

WATCH: The Met Curators highlight their favourite works

Looking closely we can see the longer bars of the chain are coloured white and embellished with tiny black dots. The technique of enamelling, which is effectively a type of glass fused at high temperature on to the surface of precious metals, had improved greatly in later medieval times such that Renaissance goldsmiths could apply brightly coloured enamel in thin layers over intricate gold surfaces. White and black as seen here were often used in conjunction with coloured gems.

I have seen similar gold and enamelled chains from the Cheapside Hoard, a spectacular find of 17th Century jewellery held today in the collection of the Museum of London. From this collection stylistic and technical parallels are made to the Ottoman Empire in what is now Turkey and Greece. It was common for goldsmiths to travel to centres of production across Europe and the international availability of printed jewelry designs caused a blend of jewelry styles to occur all over Europe.

The trading of gemstones was at the very core of this exchange of ideas and technologies, exotic and desirable materials entering northern Europe; emeralds from Brazil, diamonds from India, sapphires from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and rubies from Borneo (Myanmar).

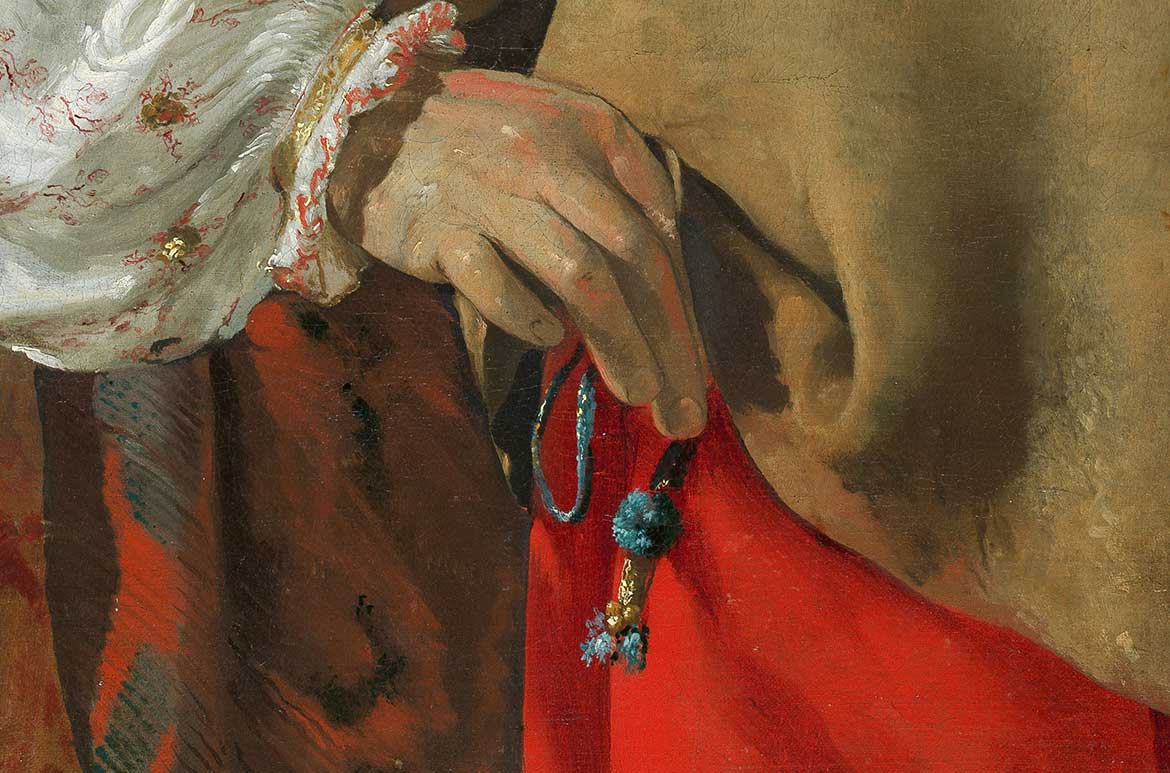

Our young man, likely a beneficiary of the Renaissance ancilliary mercantile bonanza is soon to be cleverly divested of his coin purse with its tassel pull tie, and long chain of gold bars.

Barbara Heath is a Brisbane-based jewellery designer

The Fortune-Teller

In The Fortune-Teller c.1630s, Georges de La Tour celebrates the theatre of the street. The richly attired young man has a wary eye on the old woman offering to read his fortune for a price. But it is her three beautiful companions who are robbing him blind — unobtrusively lifting treasure from his pocket and detaching a gold medallion from the long chain slung across his shoulder.

The luminous beauty of the man and woman to his left contrast with the drama and intrigue of the scene, in which the four ‘fortune-tellers’ are as lavishly dressed as their well-to-do mark. La Tour places contrasting colours and textures joyously against one another: pink against camel, orange against gold and a glistening hint of turquoise. The Fortune-Teller, which was discovered in the mid-twentieth century, is a moral tale at heart and has become one of La Tour’s most celebrated works.

This Australian-exclusive exhibition was at the Gallery of Modern Art from 12 June until 17 October 2021 and organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and Art Exhibitions Australia.

#QAGOMA #TheMetGOMA