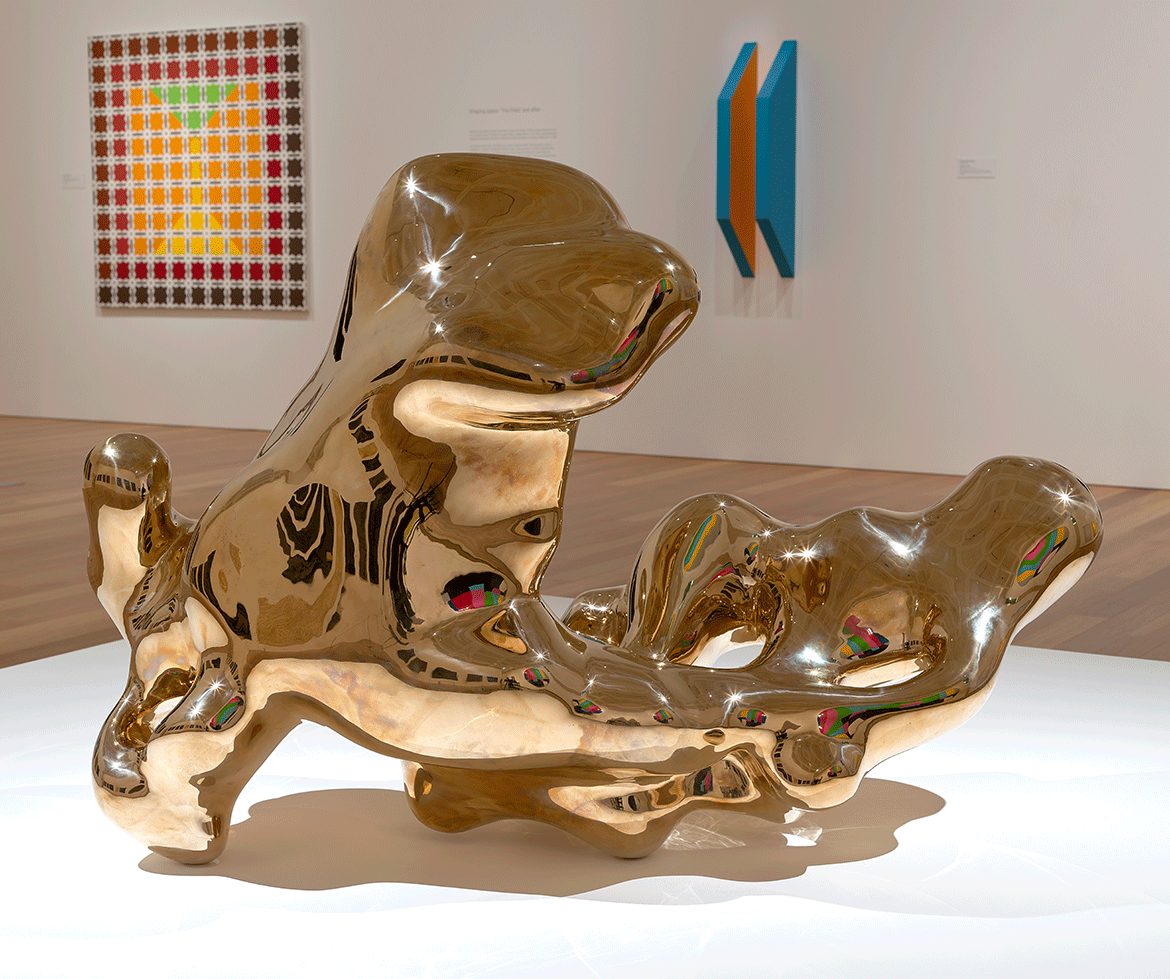

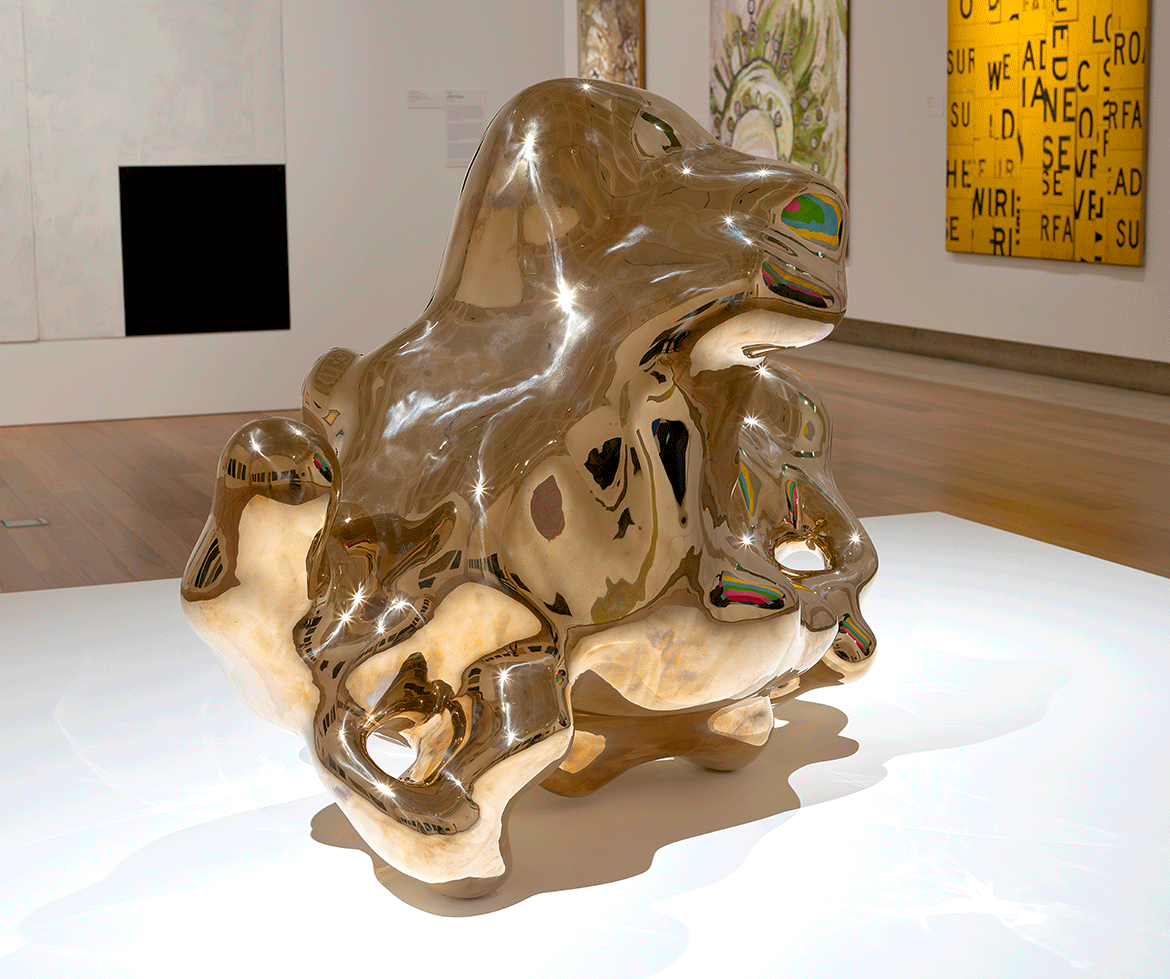

‘Living Patterns Contemporary Australian Abstraction’ at the Queensland Art Gallery until 11 February 2024, features the work of contemporary Australian artists who deploy methods of abstraction — obfuscation, codification, reduction — to create their artworks. Mediums vary — from painting and conceptual techniques to sculpture and digital imagery — as do the artists’ concerns, which include topics such as queer identities, Aboriginal cosmology, international politics and intersections of global art history.

DELVE DEEPER WITH THE CURATORS ESSAY: Curating abstraction

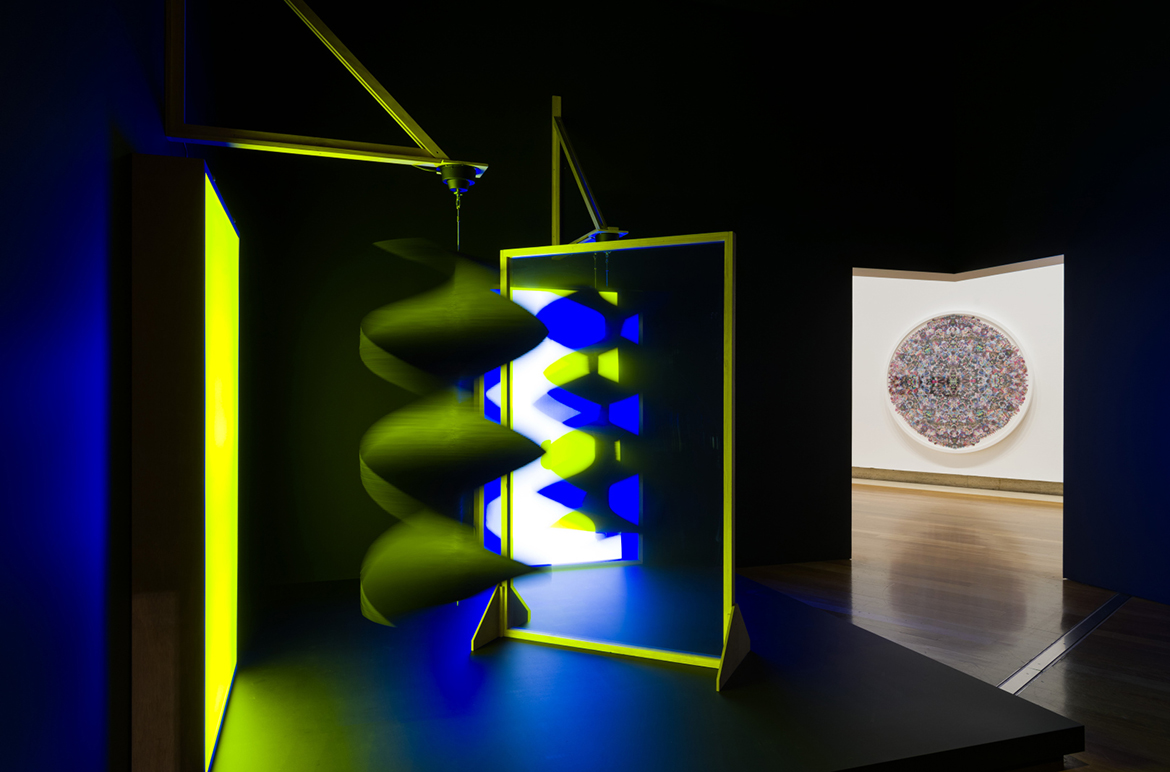

Legacies of European and American hard-edge painting and minimalist sculpture resonate in many practices throughout the exhibition. The monumental scale and circular format of Scott Redford’s Reinhardt Dammn: Things the mind already knows 2010 (illustrated) also pays homage to the shaped canvases of the 1950s and ’60s favoured by American colour field painters Kenneth Noland (1924–2010), Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015) and Frank Stella (b.1936). Yet, Redford pokes fun at the weight of art history, entangling these art historical references with the television test pattern as a symbol of ‘low culture’.

Scott Redford ‘Reinhardt Dammn: Things the mind already knows’ 2010

Artists in ‘Living Patterns’ are inspired by broader histories of abstract art. For instance, Vivienne Binns (illustrated) and Hossein Valamanesh pay tribute to the use of geometric patterns in Islamic architecture, which infuses these principles into everyday life. While artists such as Salote Tawale and Simon Wilson Pitjara use items from hardware stores and found materials to continue aesthetic practices that have customary links to their elders and ancestors.

Vivienne Binns ‘Fig and Tiles’ 2019

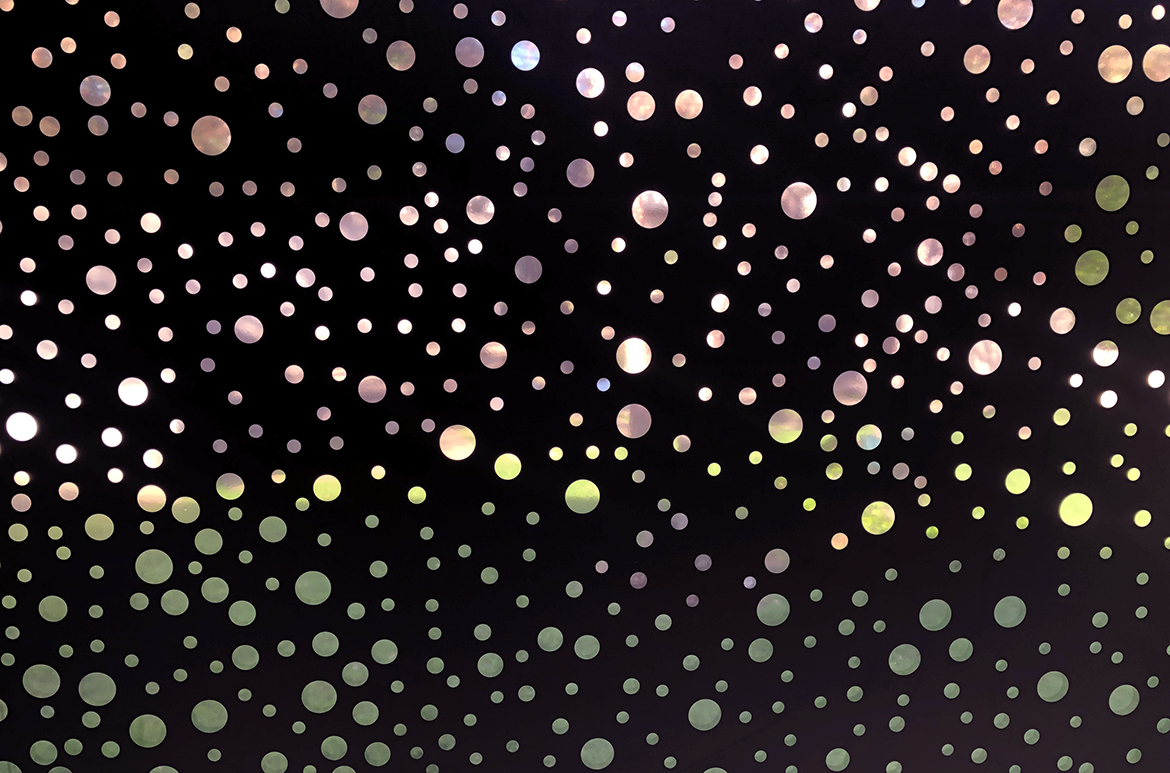

Daniel Boyd looks at the social and cultural ‘blinders’ though which historical images are viewed. Using a technique of copying artworks, cultural objects and historical photographs by hand — including the image of labours on a Queensland cane farm as seen in Untitled (HNDFWMIAFN) 2017 (illustrated), which references the state’s history of indentured Indigenous and Pacific labourer — at large scale, Boyd then leaves the image visible only through small dots while the rest of the canvas is covered in charcoal. For ‘Living Patterns’, the artist has created a site-responsive commission at the entrance to the Queensland Art Gallery, adapting the obscuring technique from historical images to contemporary life. This new window treatment covers the glass wall in a black-dotted surface so that the view outwards is reduced to small circular lenses.

Daniel Boyd ‘Untitled (HNDFWMIAFN)’ 2017

Daniel Boyd ‘Untitled (-27.4721524, 153.0181102)’ 2023

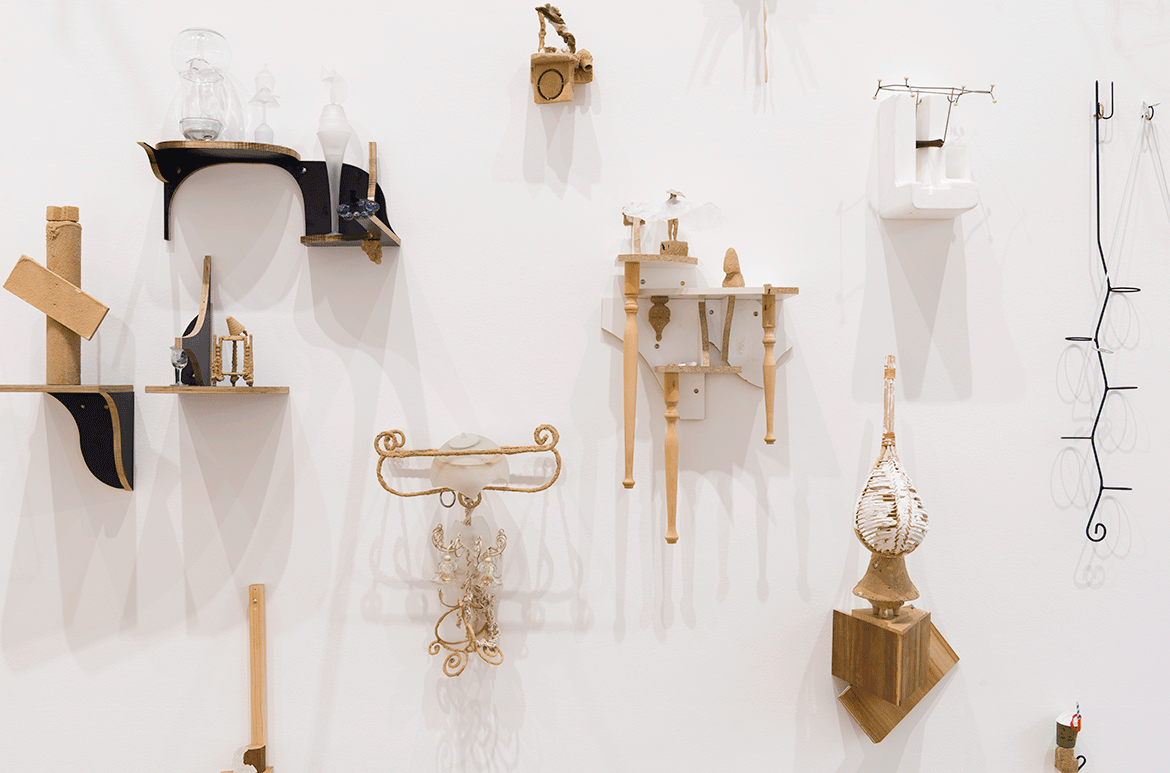

The exhibition also highlights artworks in which the human form and bodily relations can be evoked without reverting to figuration, the history of which is loaded with gendered images. Tyza Hart’s series of blank painting boards jump off the wall to lean and flop across the floor of the gallery (illustrated), as if imbued with a light touch of animism. An alternative to simply gazing upon an inanimate painting, viewers are instead positioned to navigate a physical, spatial relationship to these human-scaled sculptures. Abstraction enables discussions of the body that are liberated from the images of old, allowing artists to envision forms of the self through new metaphors. Kate Bohunnis’s sculptures often feature metal from which soft materials hang and stretch: in an active accumulation (tense) (illustrated) 2020/23, a long piece of pink latex extends from the floor to the ceiling of the gallery space, with metal hooks at either end placing this ‘skin’ under tension. Latex has a strong association with the body, from medical gloves to condoms, and thus evokes both pleasure and pain.

Tyza Hart ‘Assuming a Surface’ series 2018

Kate Bohunnis ‘an active accumulation (tense)’ 2020

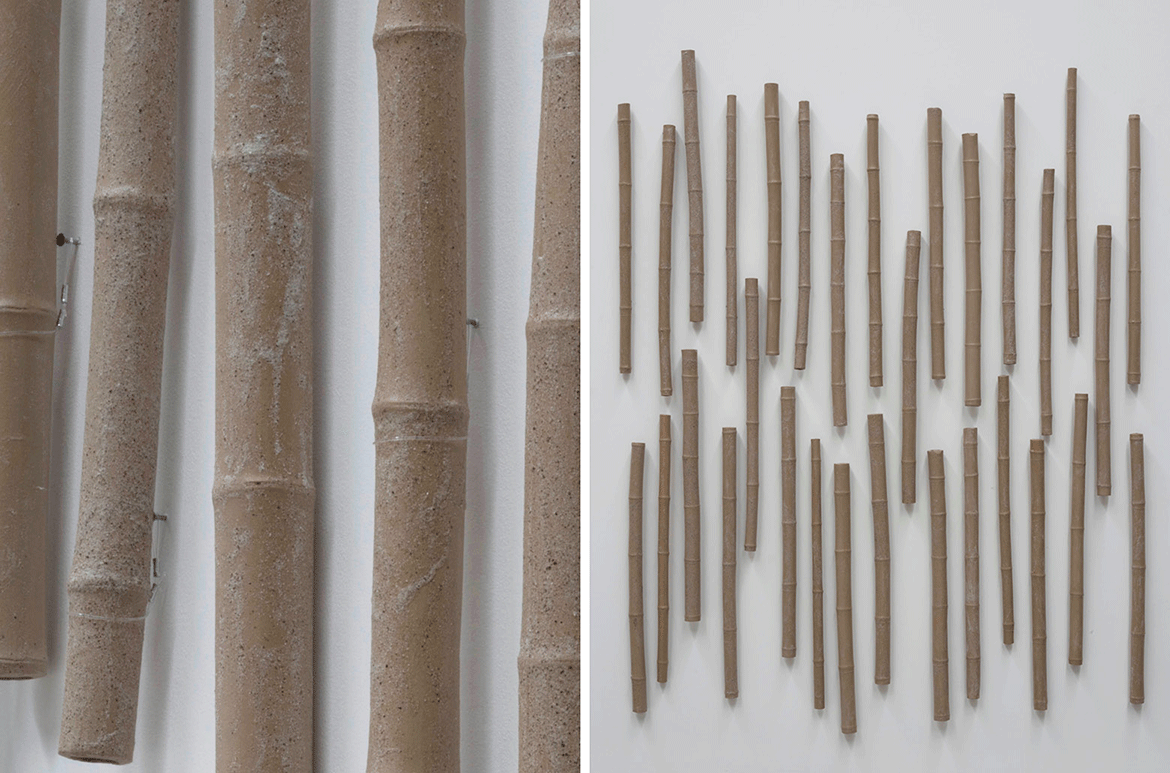

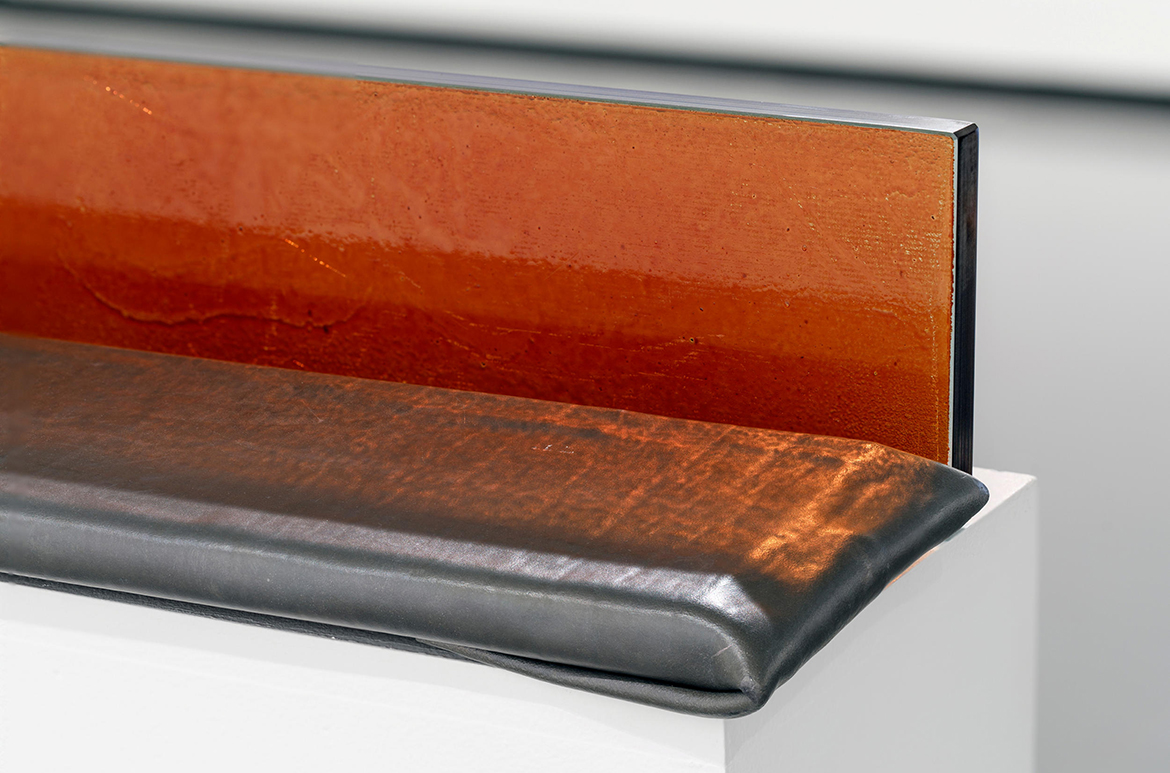

Evoking relationships and reorienting the gaze is also a strong part of d harding’s practice. The size of objects in Moonda and The Shame Fella 2018 relates back to the artist’s own body. A long piece of glass protrudes beyond the edge of the plinth; one of its sides is covered with the amber-coloured gum of the grass tree (Xanthorrhoea australis), which was applied using the artist’s own breath, further imprinting their body into the sculpture. Lying next to this length of glass is a piece of lead, the shape of which implies that there might be a similar piece of glass wrapped within its folds. Without a visible opening, this remains an assumption. The viewer not only ponders the work’s composition, its materials, textures and colours, but also their own lack of access to it. harding is well-known for covering, overpainting and obscuring elements in their artworks. This approach draws attention to the culturally inflected nature of expectations regarding who has the right to access images and knowledge. It is customary in most Aboriginal societies — such as the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples from whom harding descends — for knowledge and its associated imagery to kept from uninitiated subjects for reasons of cultural safety.

D Harding ‘Moonda and The Shame Fella’ 2018

EXPLORE THE LIST OF WORKS: Artworks with abstract characteristics by Australian artists

There are political implications to valuing such an artwork on an aesthetic level while also understanding that it contains information the viewer does not have the right to know. In an environment where transparency is increasingly considered a shared value, its limits — as defined by techniques of concealment used by both the most powerful and powerless in society — remain under-explored. As poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant posits:

There’s a basic injustice in the worldwide spread of the transparency and the projection of Western thought. Why must we evaluate people on the scale of the transparency of ideas proposed by the West? . . . As far as I’m concerned, a person has the right to be opaque. That doesn’t stop me from liking that person, it doesn’t stop me from working with him, hanging out with him, etc. A racist is someone who refuses what he doesn’t understand. I can accept what I don’t understand.1

If the establishment and continuance of colonisation in Australia was furthered through the documentation of the land and its people in order to possess them, perhaps a greater, more nuanced respect for codification can help to reset our mindset.

Ellie Buttrose is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art, QAGOMA

This text is adapted from an essay first published in QAGOMA’s Members’ magazine, Artlines 3-2023. Find out more about the artists of ‘Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction’ with a free digital catalogue and more on Collection Online. Get up close and personal with your favourite abstract works and reflect on the exhibition’s painterly experiments, sculptural investigations and illuminating installations.

Endnote

1 Édouard Glissant, trans. B Wing, Poetics of Relation, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1997, pp.185.

‘Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction’ is on display in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Gallery (Gallery 3), Gallery 4 & Watermall from 23 Sep 2023 – 11 Feb 2024.

Colour Box: Abstract Cinema

Free screenings this week & upcoming

To celebrate the centenary of the 16mm gauge film format and in response to ‘Living Patterns’, the film program ‘Colour Box’ brings together a selection of contemporary and archival 16mm experimental films to highlight the format’s long-standing relationship with abstract cinema.

#QAGOMA