From June until late October, the Gallery presents its largest exhibition of contemporary Indigenous Australian art, which aims to facilitate what Carly Lane describes as a ‘truly national conversation about nationhood’. Celebrate the opening weekend on Saturday 1 June by enjoying a day of discussions, workshops and talks by artists, performers, writers and curators ending with with a night of music, and a chance to see the exhibition after hours. At Up Late, enjoy special musical performances by Archie Roach, together with the Medics and special guest Bunna Lawrie (Coloured Stone).

Inspired by songs that reference Australianness, including Peter Allen’s iconic anthem, ‘I still call Australia home’, this major exhibition kicks off the Gallery’s winter exhibition program. Exhibition curator Bruce McLean, Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, is among the next generation of curators directing discourse in Australian contemporary art. ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ features over 300 works by more than 130 artists from every state and territory across Australia, and dominates the ground floor of GOMA, presenting a truly national conversation about nationhood as experienced and told by contemporary artists of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage. It forms part of a wider Australian narrative about being Aussie: notions of mateship and courage epitomised by the Anzacs of World War One, a fair go for all in the lucky country, and our love of football are some of the better known. But there is more to it than mateship, meat pies and sport; alternative, competing and even reaffirming narratives glimmer in the stories and experiences of every Australian. ‘My Country’ goes some way toward presenting these other narratives.

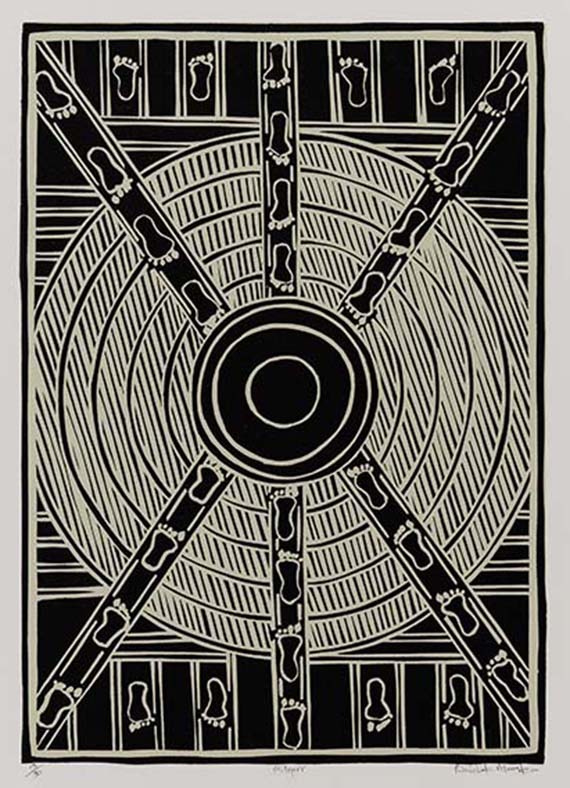

Drawn from the Gallery’s Collection and including works by Vernon Ah Kee, Brook Andrew, Destiny Deacon, Archie Moore, Doreen Reid Nakamarra, Judy Watson and many more, the exhibition spans more than three decades to present the artists’ relationships, connections and conceptions of Australian-hood. Two installations have been commissioned specifically for the exhibition: Trust the 2% 2013 by Reko Rennie and Fluid Terrain 2012 by Megan Cope, which can be found in the Gallery’s Foyer and River Room respectively. A plethora of new and old media, such as paintings, linocut and digital prints, film, photography, natural pigments, light installations, and delicate paper sculptures, flesh out these Australian stories and experiences via the three themes — ‘My country’, ‘My life’ and ‘My history’ — that steer the exhibition. Each story, experience and work of art relates to each artist’s ‘understanding of this shared physical, political, social and cultural space and place’. 1

Visitors to ‘My Country’ will likely walk away with a new schema that links ‘Black’ and ‘Australian’ together, in our history, in the present, and in the future. In this respect, the exhibition is both ambitious and timely. It is ambitious because it attempts to introduce a new conversation about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It addresses our experiences of being Australian, a condition and identity marker often overlooked by and for the First Peoples of this country. What it is to be Australian is an interesting experience to consider; admittedly this is only something I reflect on when I’m outside of my usual routines and surroundings or away from home. As an inclusive and forwardthinking nation, it is time to think beyond pre-existing narratives and fixed notions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, art and culture.

Musical lyrics, penned in different times and circumstances, also punctuate the exhibition’s stories, experiences and themes. The inclusion of musical references is clever, and is also one of the defining features of the exhibition, showing great curatorial creativity. McLean especially references eminent black singers and songwriters, including Australian hip-hop group The Last Kinection, throughout the exhibition. By doing this, he makes obvious the role that ‘both art and music have in shaping national and cultural psyche and identity’ and draws attention to that fact that every biography has a corresponding soundtrack.

‘My Country’ deliberately holds little back. It celebrates and challenges a broad spectrum of views about what it means to be Australian. The artists ‘tell it like it is’, articulating experiences without fear or favour or conforming to dominant views held in or outside their communities. The highs and lows, the joy and pain, and the continuities and contradictions of being Australian fold in and away from each other across the exhibition. ‘My Country’ shows that art does mirror life.

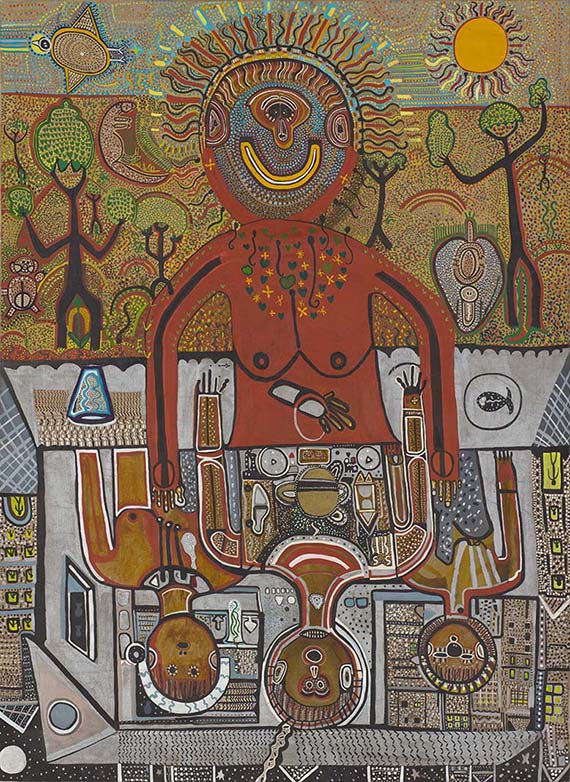

Symmetries and convergences are evident across the exhibition and its three themes. Alongside the conversations set out by McLean and the artists, audiences will undoubtedly build their own associations between individual works in the show. Suites of prints by Banduk Marika and Michael Cook and a painting by Trevor Nicholls demonstrate just one of the many links within the exhibition. Individually, the works present complex stories and experiences, but together they narrate more widely shared, lived experiences within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia. Marika’s black and white linocut prints of the Djang’kawu sisters show a creation narrative of the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land; Michael Cook’s digital prints from his ‘Civilised’ series 2012, depict Aboriginal men and women wearing and carrying the tools of the three Cs — Christianity, civilisation and colonisation; and Nicholls’s two-part painting From Dreamtime 2 Machinetime 1979 portrays two different scenes — figures in the top half of the canvas exist in nature, while the figures in the bottom half reside in a built environment. All three works reflect different parts of a single story about being Australian. They also reflect the continuum of life, how we are born, transformed and deal with the ensuing fractures, dualities and adjustments we encounter — and, in this case, the life of a Black Australian. ‘My Country’ also features a consortium of individual works in which its power is at once paramount and immediate. Bindi Cole’s large wall installation I forgive you 2012, featuring the statement drafted in emu feathers, is one such work.

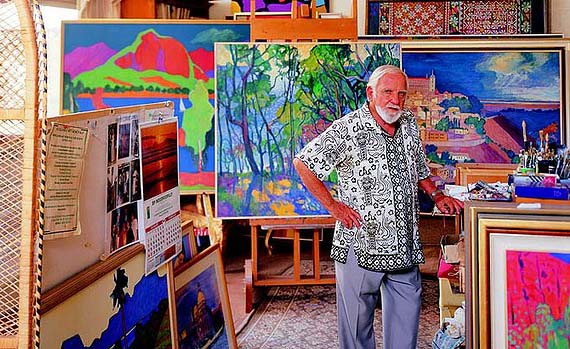

‘My Country’ is a landmark exhibition. Like the Gallery’s exhibitions of Indigenous works before it, including ‘Balance 1990: Views, Visions, Influences’ (1990), ‘Story Place: Indigenous Art of Cape York and the Rainforest’ (2003), and ‘Land, Sea and Sky: Contemporary Art of the Torres Strait Islands’ (2011), ‘My Country’ marks the next stage of development and maturation in GOMA’s approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. This is the first major exhibition conceived and curated by Bruce McLean for the QAGOMA. He joined the Gallery in 2002 to assist the development of ‘Story Place’ and has emerged as a leading voice and advocate of contemporary art within the Australian Indigenous art industry. As a curator and author, McLean is highly respected among his peers. His introductory essay in the exhibition’s accompanying publication is testimony to his ability to contribute as well as direct the discourse surrounding contemporary art by artists of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage. In developing shows such as ‘My Country’, he and the Gallery help narrow the divide that posits art by Indigenous artists outside the wider narrative of Australian contemporary art and life. For some, the existing divide is merely a result of the uniqueness of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and culture. While this may or may not be the reason, the distinctiveness of Aboriginal and Islander art need not be a barrier, but rather a conduit, to the inclusion of our voices in more Australian and international conversations.

‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ is at GOMA until 7 October. The exhibition publication is available for purchase from the QAGOMA Store and online.

Carly Lane is a member of the Kalkadoon people and independent curator based in Perth. She specialises in Aboriginal art, anthropology and curatorship and has over 15 years’ experience working in museums and galleries in Perth and Canberra.

Endnote

1 Bruce McLean, ‘This land is mine/This land is me’, My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2013, p.13.