In 1966 oral historian Hazel de Berg asked Grace Crowley (28 May 1890-1979) to talk about her friend and colleague Ralph Balson (13 August 1890-1964). Crowley spoke of her surprise and envy at the ease with which Balson painted his first abstract works: ‘Balson I believe to have been born an abstract painter. He was born that way, while I had to be educated that way’.1 Although they had known each other in the 1920s, when Crowley was the teacher and Balson a pupil at the weekend sketch classes at Julian Ashtons Sydney Art School, it was not until many years later that they would develop a deep and abiding friendship.2 Balson inspired Crowley, though, ultimately, it was his career that benefited the most. ‘You built on each other’, comments Hazel de Berg in the interview. ‘Yes, that’s right, we built on each other’, agreed Crowley.

In 1926, with her friend Anne Dangar, Grace Crowley went to France where for almost five years she studied with two of the best teachers of the day, André Lhote and Albert Gleizes. As early members of the cubist movement, both Lhote and Gleizes had exhibited with the Section d’Or group in Paris in 1912 but had, by the late 1920s, shifted from their original theoretical and aesthetic positions. Lhote was especially important to Crowley’s artistic development. She attended his academy in Montparnasse and later, between 1927 and 1929, visited his summer school at Mirmande with Dangar and Dorrit Black.3 Crowley said…

I saw for the first time the force that a drawing gained by being simplified into geometric shapes. I learned for the first time about dynamic symmetry. It was a revelation to find that in the Louvre the paintings I’d admired were constructed on a geometrical basis.4

Lhote’s teaching derived from Cézanne and was more conservative than the work of radical cubists, such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Despite an adoption of cubic form and subsumed colour, Lhote still adhered to representational subject matter — the nude, the landscape, the still life — and practised a conventional post Cézanne faceting as sen in Femme à la cuisine (Woman in the kitchen) c.1942 (Illustrated). This technique can be seen in Crowleys Torso, study in volume 1929 (Illustrated). In Torso…, the cubification of the nude contrasts with the elaborate, flatly painted patterned background. The torso’s conical breasts and muscular arms give an impression of volume and space, while adhering to classicist conventions. With this work Crowley is still struggling to come to terms with the more radical dictums of Lhote’s teaching. He stressed the necessity for art to contain a natural order of proportion, rhythm and geometry and these lessons became deeply imbued in Crowley’s art. It was also at this time that Crowley first became aware of the purist movement led by Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier) and briefly attended the former’s classes in Paris.

André Lhote ‘Femme à la cuisine (Woman in the kitchen)’ c.1942

Grace Crowley ‘Torso, study in volume’ 1929

Returning to Australia in 1931, Crowley became involved with the Modern Art Centre established in Sydney by Dorrit Black and eventually set up her own school with fellow artist and friend Rah Fizelle. Crowley said of their teaching: ‘We were united in one belief, the constructive approach to painting, and this insistence on the abstract elements in building a design was the keynote of teaching of both Lhote and Gleizes’.5 Crowley had been introduced to Gleizes’s theories by Anne Dangar who had read his La Peinture et ses Lois. Gleizes’s tutoring asserted the importance of animating flatness so that a new perspective was created. ‘Flat planes were simultaneously to be set in motion and made to evoke space by being shifted across one another as if rotating about tilting, oblique axes.’6 These ideas were encouraged once again by Dangar who, having returned to France, continued to send Crowley small pocket-sized studies (pochades) for her to copy. It was through these that Crowley first understood the practice of sinking one form or plane into another. Similarly Lhotes notion of passage, in which a composition was integrated by passing one form over another, produced the impression of colours floating into one another.7

The partnership with Fizelle lasted six years before Crowley formed a connection with Ralph Balson. Balson, who had worked as a house painter from the age of 12, was mostly self-educated. He was an avid reader, not just of art books, but of poetry, music, novels and scientific theory. Crowley soon found that there was little she could tell him about overseas artistic trends.8 In about 1934 Crowley, Frank Hinder, Balson and Fizelle engaged a model and painted together on Saturday mornings at a studio at 215 George Street, Sydney. It was during this period that the friendship of the two artists strengthened.9 Crowley was impressed by Balson’s ability to grasp the essentials of constructive art without ever having studied abroad. He had, she commented, a natural instinct which made her sometimes feel that her own work was vastly inferior. Balson, said Crowley, would ponder on what to paint all week, realising it only on the weekends. His work as a house painter thus not only afforded him much time for thinking, it also accustomed him to handle large areas of paint with dexterity and ease’. He did not make preliminary sketches but memorised what he saw and then recorded it as quickly as he could on arriving at the studio.10 Crowley felt that the pupil had become the teacher.

Throughout the 1930s Crowleys school maintained a radically avant-garde approach, based on Lhotes teachings, which was well beyond the scope of most of its students. While it was a dynamic time — the Grosvenor Gallery strongly supporting the new trends expounded by Crowley, Fizelle, Balson and Frank and Margel Hinder — the majority of art practice and teaching, not to mention the art market, was conservative.11 Sydney, on the whole, favoured a modified form of Modernism derived from the English, rather than the French, tradition. This could be seen in the work of Roland Wakelin who, along with others with a similar style, showed at John Young’s Macquarie Galleries. Dorrit Black, Crowley and their circle felt that this ‘Anglified’ Modernism lacked the authentic ‘significant form’ of the French-inspired version, which was based instead on a deep understanding of both geometry and rhythm.

Though Crowley was already familiar with the theory of dynamic symmetry through André Lhote, it was once again put on the artistic agenda by Frank and Margel Hinder after their arrival in Australia in 1934. As Renée Free has noted, Frank Hinder read widely in the area of rhythmic form in art and possessed a large library of books which were no doubt circulated amongst his friends.12 Originally devised by the American mathematician Jay Hambidge, dynamic symmetry was a complex theory of the application of geometrical analysis to art. Drawn from the Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, Hambidge’s theories were first published in the monthly magazine Diagonal, as a series of articles written by Hambidge in the winter of 1919 -20. These were published later in 1920 as The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry.13

Dynamic symmetry, wrote Hambidge, was obtained from the organic world and the ‘five geometrical solids’.14 It was based on notions of transition and movement, which can be traced back to the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians and which distinguished it from static symmetry. Hambidge also argued that artistic instinct and feeling must be tempered by intellect and knowledge, otherwise ‘incoherence’ would follow, and it is with this last point in particular that similarities with 1920s Classicism arose.15

While the theory was of most significance to the art of the Hinders, it certainly had an impact on Crowley, if not on Balson. Both Crowley and Balson were experimenting with pure abstraction and moving even further away from the Gleizes-influenced facetting, by using solid blocks of colour, a technique drawn from Henri Matisse. However, Crowley’s abstracts were freer and consciously asymmetrical. Balson’s works, on the other hand, were more static and relied on the balancing of horizontals and verticals.

In 1939 Crowley, Balson, Fizelle and Frank and Margel Hinder, along with Eleonore Lange, Frank Medworth and Gerald Lewers, came together to show their work at ‘Exhibition 1’ held at David Jones’ Exhibition Galleries. Though their intention was to create ‘a new realm of visual existence’,16 critics and the public responded coolly to their work. All persisted with abstraction, although with separate and individual distinctions. In 1941 Balson produced an exhibition of purely abstract works, entitled ‘Constructive Paintings’, drawn from his study of Piet Mondrian.17 The purity of Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism and his belief in fundamental order initially had great appeal for Balson. His early 1940s works carry a hard-edged simplicity which, as art historian Mary Eagle has identified, was a foretaste of the Minimalism of the late 1960s and early 1970s.18 Mondrian, he later admitted, was the ‘single greatest influence’ on his work.19

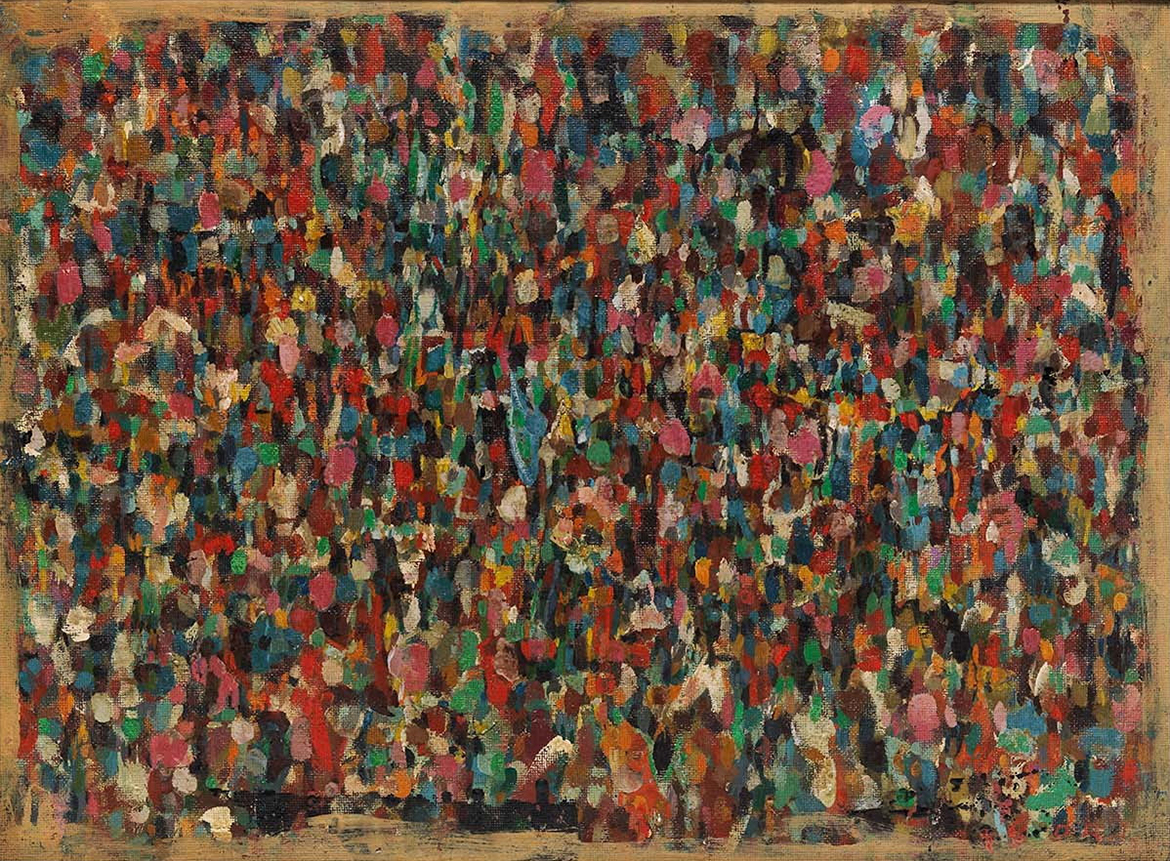

Ralph Balson ‘Untitled’ 1961

Mondrian’s search for universal truth (sometimes through theosophy) appealed to Balson’s own philosophical and spiritual needs, though, as Bruce Adams has noted, ‘Balson’s geometric art was never as cool and elemental as Mondrian’s’.20 By the mid-1940s, particularly the period immediately following the development of the atom bomb, Balson came to reject the view of the universe as rigid and harmonious, in favour of a much more complex and organic belief system. The idea of an orderly universe seemed impossible to sustain in light of scientific developments such as nuclear fission and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and this led Balson to take a totally new direction in his art.

While Balson’s earlier work in the 1940s made much use of the circle as a definitive shape and circular motion as a compositional device, in Constructive painting 1947 (Illustrated) squares and rectangles seem to ‘float’ randomly across the canvas, shifting above, below and behind one another. These ‘patterns of great complexity’, as painter and critic James Gleeson described them, signified the direction that both Balson and Crowley would take over the next few years and would seem to be (at least in Crowley’s art) the painterly evidence of Hambidge’s ‘rectangle of the whirling square’. Both Crowley and Balson, according to Frank Hinder, had long been experimenting with coloured papers to achieve this effect and by the early 1950s both were painting abstract compositions of overlapping geometric blocks of tonal colour, though Balson stuck more rigidly to a formal grid than Crowley.21 Colour, too, is reduced (though not as reductive as some that followed in the early 1950s), with bands of barely distinguishable blue backgrounding pale pink, grey and yellow. As with Crowley’s painting, the creamy texture of the paint itself has been allowed expression — indeed Balson’s enjoyment of the physicality of the medium is palpable.

Ralph Balson ‘Constructive painting’ 1947

Grace Crowley ‘(Abstract)’ 1951

Balson’s influence on Crowley’s art is best demonstrated by her 1950s abstracts. In her Abstract 1951 (Illustrated), for example, the sky blue and hot pinks serve as a background to a humming mix of egg yolk yellow and bright orange, while the ‘rectangle of the whirling square’ spins across the canvas from right to left. Shapes and colours collide and float so that all sense of perspective is lost. Paint has been applied thickly, the brush dragging at the oil to create a deeply grooved effect. Crowley’s painting has an easy fluidity not present in either Balson’s or Frank Hinders work. This relaxation of form probably resulted from Crowley combining Hambidge’s theories with those of Lhote and Gleizes, whereas Balson drew many of his influences from Mondrian and contemporary French painting, and later, American Abstract Expressionism (towards which he would increasingly lean)22

Crowley and Balson remained painting partners and the best of friends until Balson’s death in 1964. They painted together at her cottage in Mittagong, and met up in Fondon and Paris in 1960 where they worked and visited galleries. A combination of self-deprecation and low self-confidence conspired to limit the number of surviving paintings by Crowley. She destroyed many of her own works when she closed her studio in George Street, stating matter-of-factly that ‘even the most famous artists do bad work’, and she was clearly uncomfortable with interviewers in speaking of her own art and her role in developing abstraction in mid-twentieth-century Sydney.23 Balson, on the other hand, enjoyed more success as time wore on, holding a total of eight solo exhibitions and many group exhibitions until his death in 1964.

Their deep friendship was easier to sustain than their collaborative success. Throughout their long partnership, Crowley loved to watch Balson paint. ‘People thought him rather morose, and he wasn’t… he was the happiest thing you could think of.’24

Edited extract by Dr Candice Bruce, former Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA from Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998.

Endnotes

1 Hazel de Berg, ‘Interview with Grace Crowley’, 1966, tape recording, National Library of Australia, Canberra, published in Ralph Balson 1890-1964 [exhibition catalogue], Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, 1989, pp.2-3. The Hazel de Berg recordings were an oral history project of the National Library of Australia, Canberra.

2 After studying at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School (1915-18), Crowley met with family opposition to her chosen career. To support herself financially, she became Ashton’s assistant for several years, taking over from Elioth Grüner. Her family once again supported her financially while she lived in France. For Balson see Bruce Adams, Ralph Balson: A Retrospective [exhibition catalogue], Heide Park and Art Gallery, Bulleen (Vic.), 1989.

3 Both Crowley and Dangar sent regular letters from Europe to the Sydney Art School which were published in the school’s magazine, Undergrowth. See Helen Topliss, Modernism and Feminism: Australian Women Artists 1900-1940, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1996, pp.70-72, and Adams, pp.12-13.

4 Grace Crowley, quoted in Topliss, p.74.

5 Grace Crowley, letters to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 28 August and 1 September 1966, quoted in Renée Free, Balson, Crowley, Eizelle, Hinder [exhibition catalogue], Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1966, p.6.

6 Christopher Green, Cubism and Its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916-1928, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1987, p.88.

7 Topliss, p.78.

8 De Berg, p.2.

9 De Berg, p.2.

10 De Berg, p.2.

11 In August-September 1939 the David Jones’ Exhibition Galleries in Sydney held a quite revolutionary exhibition of Australian modernist art entitled ‘Exhibition 1 ‘, which contained work by these artists and Frank Medworth, Eleonore Lange and Gerald Lewers, but few works sold.

12 Renée Free, Frank and Margel Hinder, 1930-1980 [exhibition catalogue], Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1980, p.14.

13 Jay Hambidge, The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry, Dover Publications, New York, 1967; originally published by Yale University Press, New Haven, 1920.

14 Hambidge described the ‘five geometrical solids’ as the ‘cube, the tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron and the dodecahedron’. See Hambidge, p.xvi.

15 Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger in their essay ‘Cubism’ (1912), however, preferred the theorem of the German mathematician Bernhard Riemann to Euclid. See Gleizes & Metzinger, ‘Cubism’, in Robert L. Herbert (ed.), Modern Artists on Art: Ten Unabridged Essays, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1964, p.8.

16 Eleonore Lange, Foreword, in Exhibition 1 [exhibition catalogue], David Jones’ Exhibition Galleries, Sydney, August 1939, unpag.

17 Adams, p.27.

18 Mary Eagle, Australian Modern Painting between the Wars 1914-1939, Bay Books, Sydney, 1989, p.147.

19 Adams, p.26.

20 Adams, p.27.

21 Free, p.13.

22 Adams, p.30.

23 Lenore Nicklln, ‘Grace Crowley looks back on a lifetime of art’, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 May 1975, p.11.

24 Nicklin, p.11.

#QAGOMA