‘We can make another future: Japanese art after 1989’ includes works by Yayoi Kusama, Lee Ufan, Daido Moriyama and others. This is an insight into the Heisei period and the works it inspired.

Running until September 2015, ‘We can make another future: Japanese art after 1989’ surveys the Gallery’s collection of Japanese contemporary art. The exhibition focuses on work made during the period known as Heisei in the Japanese calendar, running from 1989 to the present day. The exhibition brings together artistic responses to questions of a fixed Japanese identity and also reflects on the physical, spiritual and natural worlds, and engagements with the burgeoning field of popular culture.

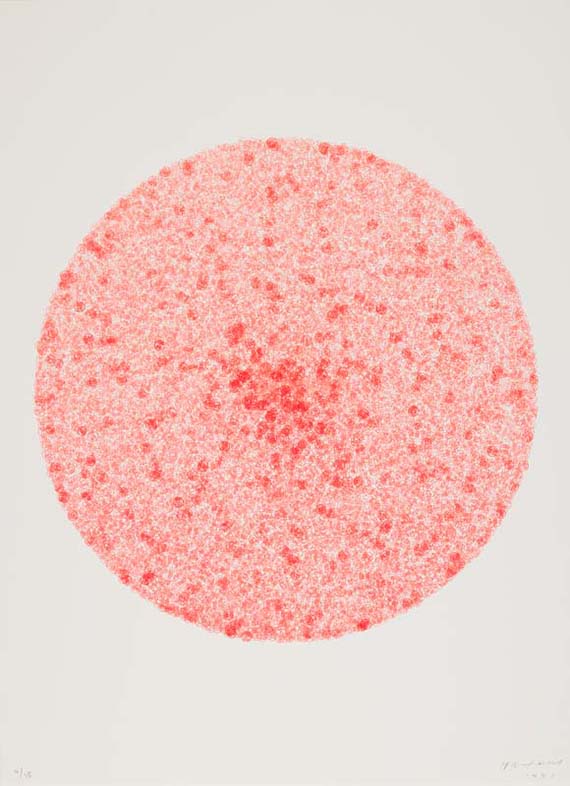

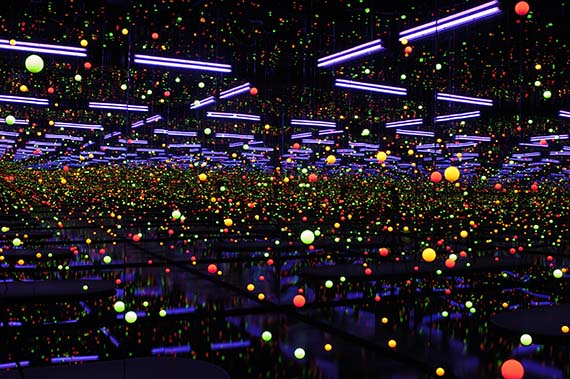

At the outset of Heisei, space, time and encounter — along with the poetry of materials and the role of humans in the natural world — were central tenets of Japanese art. Their resonance with themes in Asian philosophy fuelled the popularity of such work with Japanese and international audiences alike. Coming to international prominence at this time were Yayoi Kusama and Lee Ufan, two senior artists whose practices elaborate on notions of encounter and infinity in distinctive yet complementary ways. Seemingly unconstrained by the physical limits of the canvas, the undulating fields of Kusama’s ‘net’ paintings suggest the possibility of infinite expansion into space, while her mirrored rooms, where repetition is achieved through reflected light, represent a step toward that possibility. Lee, meanwhile, was a central figure in the Mono‑ha (‘school of things’) group of 1968–73, and was instrumental in its deeply philosophical shift from producing objects to orchestrating relationships between them as well as encounters between the audience and the work.

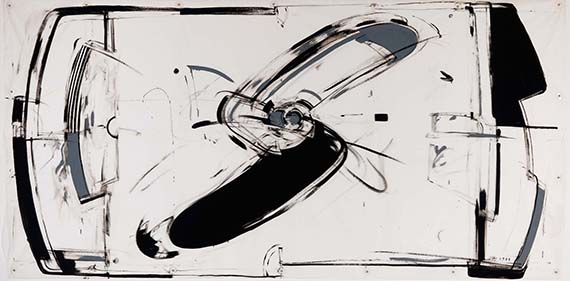

Throughout the period, dramatic installations and performances influenced by Mono-ha operated in dialogue with spatial and architectonic propositions in Japanese photography and printmaking. New discourses emerged in response to evolving cityscapes, rapid advances in technology and attendant threats of ecological crisis. From this rich context emerged the dynamic, postmodern syntheses of artists such as Hiroshi Sugimoto, Tatsuo Miyajima and Rei Naito, whose work evoked a digital sublime, the human experience of technological development, and its powerful rhetoric of transcendence and exponential change.

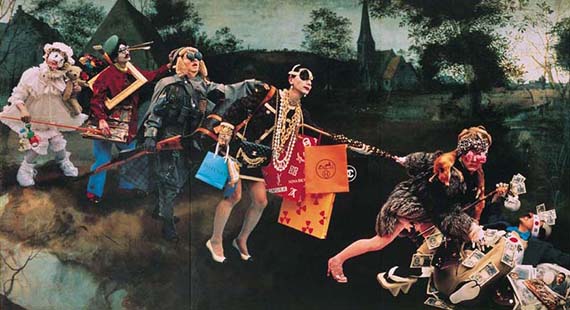

By the 1990s, Japanese consumer society had reached its feverish peak, initiating discourses centred on information overload, as well as a reassessment of cultural values. As various media consolidated the image of the Japanese city as neon-drenched megalopolis, a new generation of artists and intellectuals sought creative freedom in abandoning pretence to deeper meaning. Turning away from the pursuit of eternal truths, they looked instead to the very surfaces of popular culture.

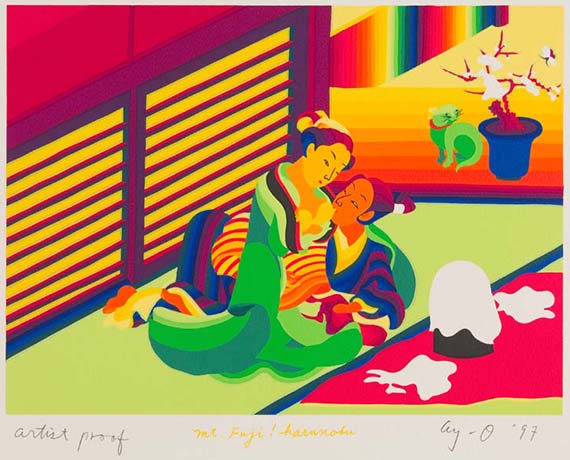

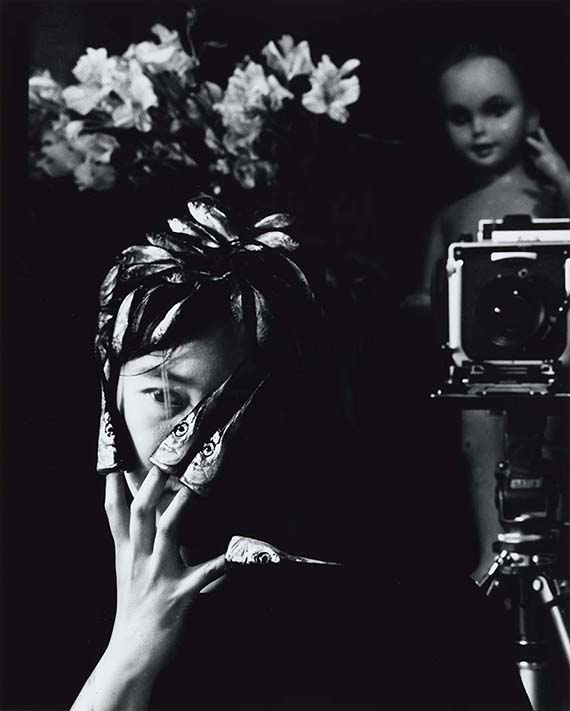

Interest in the changing textures of consumerism was not new, and senior figures associated with the international Fluxus movement, including Ay-O, Takahiko Iimura and Mieko Shiomi, maintained significant existing practices. Equally significant were photographers like Daido Moriyama, who produced streams of images in an attempt to capture aspects of the modern city that words could no longer describe. But while such work conveyed a sense of unease, a new generation felt at home with collapsing distinctions of high art and popular culture.

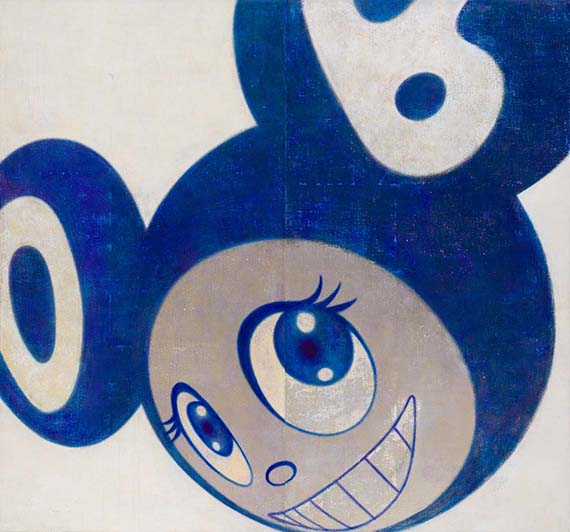

Two of the best known artists to emerge from this irreverent variant of international postmodernism were Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara. Privileging the visual and the vernacular, they respectively claimed comic books and punk rock, rather than art or philosophy, as major influences, in a surface-driven approach to representation that Murakami would characterise as ‘Superflat’.

In the late 2000s, sculpture and installation experienced a revival as alternative means of exploring visual culture in the digital age, through the work of younger figures such as Yuken Teruya, Kohei Nawa and Teppei Kaneuji. Working through pop motifs and existential dilemmas, they provide valuable reflections on shifting regimes of vision and representation.

‘We can make another future: Japanese art after 1989’ is at GOMA until 20 September 2015.