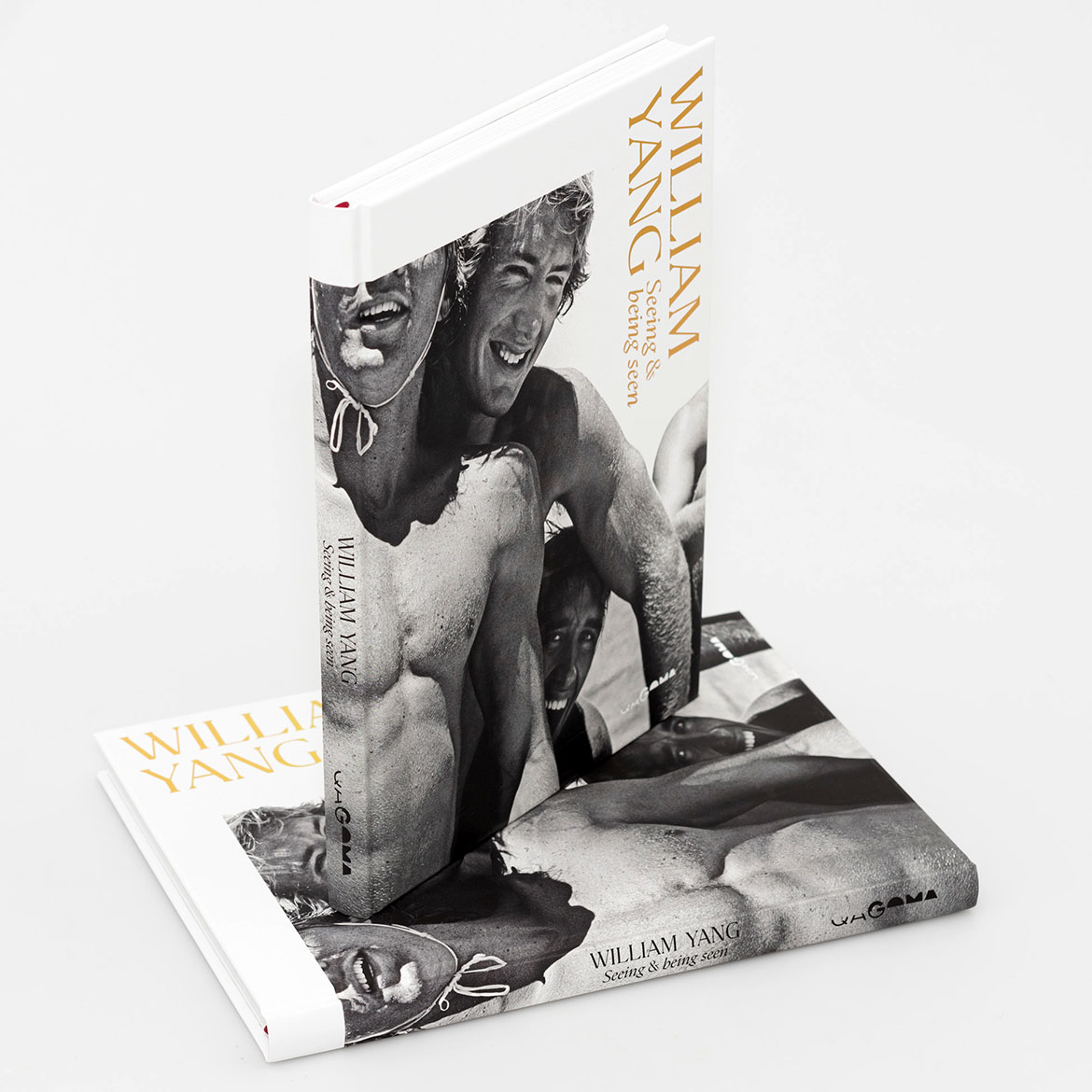

The launch of our new event cinema series kicks off on Sunday 26 February and runs across 10 unique screenings and music performances until 26 November 2023. Our ‘City Symphony’ Live Music & Film series will start with a screening of the iconic Man with a Movie Camera 1929 paired with Brisbane based post-rock band hazards of swimming naked who have crafted a new live score for the film.

Live Music & Film #2: ‘Lines’ accompanied by Matt Hsu’s Obscure Orchestra

Get tickets to City Symphony Live Music & Film series

hazards of swimming naked playing live at GOMA

City Symphony film movement

The ‘City Symphony’ film movement began in the 1920s. It was a period of rapid urbanisation and with all that movement to cities, people were thinking about the built environment and how that influenced their daily lives.

The 1920s was also at the beginnings of filmmaking as an artform. This was the era of silent cinema — Charlie Chaplin’s comedic style was swelling in popularity around the world. There were also a number of directors exploring differing styles of camera framing and editing techniques. City Symphony films are playful cinematic experimentation — part documentary, part film poem.

Man with a Movie Camera is one of the most beloved City Symphony films for its fresh, joyful, and rhythmic approach to filmmaking as well as its camera trickery — in one scene the central character towers over a city like a giant then in another he’s small enough to fit into a frothy beer mug (illustrated).

Director: Dziga Vertov ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ 1929

Brisbane based band hazards of swimming naked were a great fit for such a treasured film as they have a wealth of experience accompanying screenings at the Australian Cinémathèque, Gallery of Modern Art. Their moody sound and attention to creating a fulsome, sonic atmosphere will complement the big vision of the film.

We asked Adrian Diery from hazards of swimming naked about the crafting of this live score.

Rosie Hays / What were your first impressions of the film ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ and what did it inspire?

Adrian Diery / When I first saw the film I was struck by the adventurous approach to film making. The brothers [the filmmaking duo director and cinematographer are siblings] seem to be following their instincts in capturing everyday life, pushing the limits of their equipment, themselves, innovating camera techniques and setups. We get to see the world through the man-with-a-movie-camera’s lens, but we we’re also shown how he’s capturing the images, and then how the editor (the director’s wife) organises and pieces the film together.

Man With A Movie Camera is an incredible document of an almost blissful moment in time, it’s in the early days of the Soviet Union, after the end of the Russian Civil war, between the two World Wars, and in the very early days of Stalin before he became truly monstrous. Throughout the film there is a pervading sense of progress and hope. The streets are bustling, the everyday people are championed; in the chapters on leisure and entertainment there’s evident joy and wonder on the faces of children and adults as they swim, engage with sport and athletics, watch a magic show, attend the ballet or cinema. There’s also a spirit of adventure as the filmmakers cling to the side of train, climb into precarious positions atop of tall structures, or play with stop motion and camera tricks.

RH / What instruments will the band play?

AD / Space is at a premium when we perform at GOMA’s Australian Cinémathèque. In the past we’ve managed to squeeze some extra personnel into the corner with us, but we’re sticking to our regular line-up of guitar, bass, drums/percussion, and synth/keys. Some of the pieces we will be playing will be augmented by string and electronic arrangements we have produced specially for the performance.

RH / What kind of mood should the audience expect for your musical accompaniment?

AD / We decided to think about the film as a time capsule, we wanted to evoke a sense of nostalgia for a world lost. There’s this air of peace, civility, normality which is far removed from what we are seeing and hearing about Ukraine and Russia at present, and for us it was difficult to escape that sense of tragedy, and loss of peace. We tried to balance that sense of loss with the spirit of optimism and wonder in the film. There are also moments of high energy which we pair with the experimental sections of frenetic editing. The film also treats the medium of cinema as almost magical, and we wanted to reflect the sense of wonder that early cinema audiences may have felt. We’ve worked with you before to accompany silent films in the past. It’s rare that a band accompanies a silent film.

RH / What’s your approach to crafting a musical response to a film?

AD / Previously we have created entirely new music for our live performances for The Passion of Joan of Arc, The Last Laugh, both of which had strong characters and narrative structures. With this film, even though there is no narrative, it is organised into 6 chapters, plus a prologue, and opening credits. This gave us a strong structure to work with, inside each chapter there we identified smaller sequences, to which we could attach a single musical piece. This film was cobbled together from an abandoned project and new footage filmed, and we have adopted a similar approach, repurposing some of our existing material, and creating some new pieces specifically for this film and performance. Typically we view the film to identify scenes, characters, or motifs to which we can attach musical ideas. We will try a few ideas against scenes and quite quickly identify if something is working, or to what tempo the sequences respond well. In some cases we had an existing piece that worked well for one sequence, we could then craft a complementary piece which rounded out the remainder of the chapter. We also developed one or two novel musical motifs which could recur throughout the film to help reinforce the sense of an over-arching theme and cohesion.

RH / You’ve previously worked with filmmakers to create a film score. How is this process for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ different to scoring a film? Is it different?

AD / Often, but not always, with scoring a contemporary film, the filmmaker will provide some direction for the music they want in their film, and editor will have worked with a “temp score” to help them pace a scene, or emphasise moments of emotion or action. Silent films were usually soundtracked by a live ensemble in the theatre, but a few recordings exist of these. So, when we sit down to score a silent film, we’re beginning with almost zero musical direction, certainly not from the filmmaker themselves. Rather than scoring precise moments, we’re instead trying to create a sustained mood or transition in moods throughout a sequence. The structure and pacing of silent films is typically slower than contemporary films and allows us the accompaniment to take more time to develop and to resolve in more a musically intuitive manner.

Rosie Hays is Associate Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

Upcoming live music & film

Live Music & Film: Man with a Movie Camera 1929

Live Music & Film: Lines 2021

Live Music & Film: Harlem Streets to Stockholm Symphony 1937

Live Music & Film: City Visions, Cairo to New York 1930–2019

Live Music & Film: People on Sunday 1930

Live Music & Film: The Poetic Cities of Joris Ivens 1929

Live Music & Film: Calcutta 1969

Live Music & Film: Berlin, Symphony of a Great City 1927

Live Music & Film: Nothing But Time 1921–2012

Live Music & Film: Man With a Movie Camera (with violin) 1929

City Symphony special ticket offer

See the full series and save!

Buy 5 to 9 tickets and receive at 10% discount.

Buy 10 tickets and receive a 20% discount.

Get tickets

#QAGOMA