It’s always hard to choose just five. But if I have to pick, here are some of my favourite Brisbane International Film Festival (BIFF 2020) films.

The vitality and authenticity of the female friendships, well-crafted characters and sheer joy in Rocks is what makes this film such a pleasure to watch.

Delve into the liquid-like darkness of the cinematography for Vitalina Varela. The latest film by assured filmmaker Pedro Costa which premiered at the Locarno Film Festival 2020.

There really is nothing quite so delightfully satisfying than a gob-smacking true story told with exquisite filmmaking craft. Miracle Fishing is such a film – a true not-to-miss documentary.

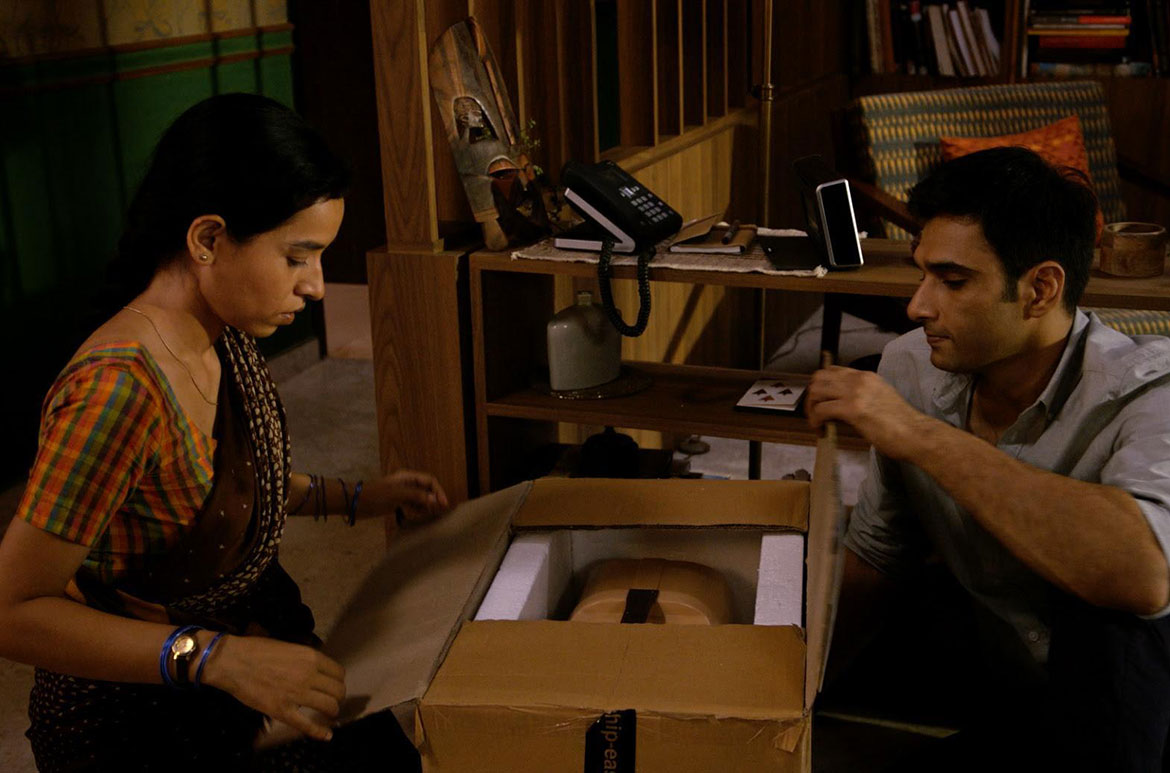

There are so many ideas crammed into this completely bonkers but miraculously coherent film – A Yellow Animal is super stylish and an outrageous combination of a filmmaker on an ego trip while also a self-aware exploration of identity, race and colonialism.

What could be more intimately vulnerable than falling asleep alongside strangers accompanied by the hypnotic sounds of New York composer Max Richter? Max Richter’s Sleep is a beautiful reminder of what makes us human.

Rosie Hays, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

RELATED: More 5 film suggestions to watch

SIGN UP NOW: Like to be the first to know? Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest cinema announcements. What are your BIFF top 5?

BIFF returns to cinemas from 1 to 11 October with multi-award-winning Australian actor Jack Thompson AM and Academy Award-nominated film editor Jill Bilcock AC as the Festival’s 2020 Patrons. Presented by the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) through its Australian Cinémathèque at GOMA, and in partnership with venues across Brisbane, BIFF 2020 will screen new release features and documentaries, special events, a short film competition and much more.

With over 70 films from 28 countries, we can’t wait to welcome audiences back for BIFF 2020 – 11 exhilarating days of unmissable cinema!

Visit BIFF.com.au to schedule your films

1. Rocks

Rocks 2019 / Director: Sarah Gavron

2. Vitalina Varela

Vitalina Varela 2019 / Director: Pedro Costa

3. Miracle Fishing

Miracle Fishing 2019 / Director: Miles Hargrove

4. A Yellow Animal

A Yellow Animal 2019 / Director: Felipe Bragança

5. Max Richter’s Sleep

Watch and Read about BIFF 2019 / More on BIFF 2020 / View the Cinémathèque’s ongoing program / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Returning to Cinemas

BIFF 2020 is one of the first major film festivals in Australia to welcome audiences back to cinemas, and we’ll be taking extra steps to prioritise the health and wellbeing of our visitors and staff. In addition, when booking, individuals/groups will be distanced in accordance with Queensland Health guidelines.

BIFF 2020 will screen at QAGOMA’s Australian Cinémathèque, and at valued partner venues Dendy Cinemas Coorparoo, The Elizabeth Picture Theatre, New Farm Six Cinemas, Reading Cinemas Newmarket and the State Library of Queensland – all part of a city-wide celebration of film.

QAGOMA is the only Australian art gallery with purpose-built facilities dedicated to film and the moving image. The Australian Cinémathèque at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) provides an ongoing program of film and video art that you’re unlikely to see elsewhere, offering a rich and diverse experience of the moving image, showcasing the work of influential filmmakers and international cinema, rare 35mm prints, recent restorations and silent films with live musical accompaniment on the Gallery’s Wurlitzer organ originally installed in Brisbane’s Regent Theatre in November 1929.

BIFF 2020 is supported by the Queensland Government through Screen Queensland and the Australian Federal Government through Screen Australia.

Artistic Director for BIFF 2020 is Amanda Slack-Smith, Curatorial Manager of QAGOMA’s Australian Cinémathèque.

Featured image: Production still from Max Richter’s Sleep 2019 / Director: Natalie Johns / Image courtesy: Madman Entertainment

#BIFFest2020 #QAGOMA