Though Australia’s link with the land is strong, and the ways in which we’ve used it have largely determined the Australian character, our interaction with the land is often contested. Here, we gain insights into works that respond to mining in Queensland.

Mining in Queensland

For Indigenous Australians, the land is everything. Through their care, the land — their ‘mother’ — has ensured the survival of countless generations. However, nonindigenous exploitation and historical injustices have deeply affected the cultural, social and economic lives of Aboriginal people, and fractured their ties with country.

We feature four Aboriginal works associated with the land that are part of a broader discourse on the removal of resources from beneath the earth’s surface. Though the inevitable sense of loss is inherent in their work, the artists deal creatively with their diminished role in managing and caring for their country. Rather than depicting damage to the land and its people through mining ventures, they take a positive approach to educate their audience and ameliorate past wrongs.

RELATED: Delve deeper into Australian Indigenous art

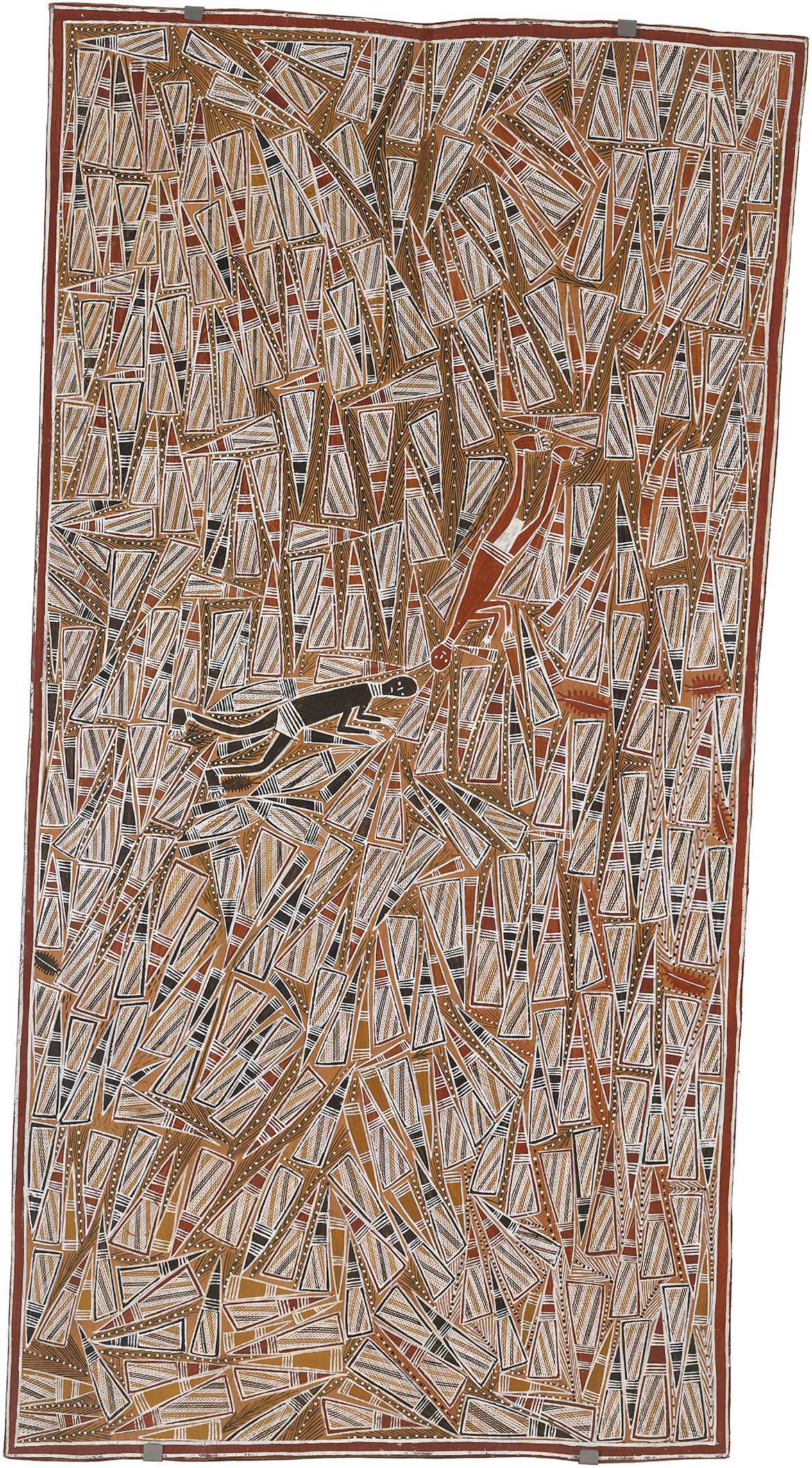

Yalangbara c.1960 is a rare collaborative painting on bark by eight ceremonial leaders from north-eastern Arnhem Land, it illustrates the major creation story of the Djang’kawu (two sisters and their brother) forming the land and laying down the cultural and social laws by which people were to live. In Yolngu law, Yalangbara constitutes a deed of ownership of the artists’ clan estates.

Yalangbara predates subsequent important collaborative barks: the magnificent Yirrkala Church Panels of 1962–63, and the historic Yirrkala bark petition. Presented at Parliament in August 1963, the Yirrkala petition was a bid to persuade the government of the time to reconsider a deal with Swiss Australian company Nabalco (North Australian Bauxite and Alumina Company), which would allow mining exploration on 300 square kilometres excised from Yolngu land on the Gove Peninsula. Although unsuccessful, this foray into native title litigation (known as Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd) triggered a greater awareness and recognition of Indigenous Australian people, and paved the way for constitutional change acknowledging their rights to control their land. The petition still hangs in Parliament House, Canberra.

Though financial compensation and protection of sacred sites were negotiated, the concept of extracting minerals from the land was foreign to the Yolngu, and seen as a severe transgression of Aboriginal culture. Since then, endless tonnes of earth have been extracted for bauxite, which is transported on rubber conveyor belts for offshore processing into aluminium, which, as Bonhula Yunupingu comments, returns to Yirrkala ‘. . . as a can, as a beer can’.1 Painful residual scars, on both the land and the people, persist.

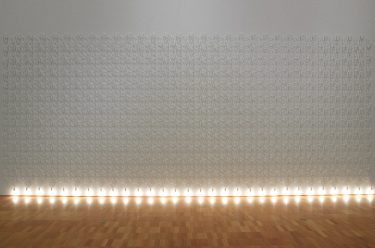

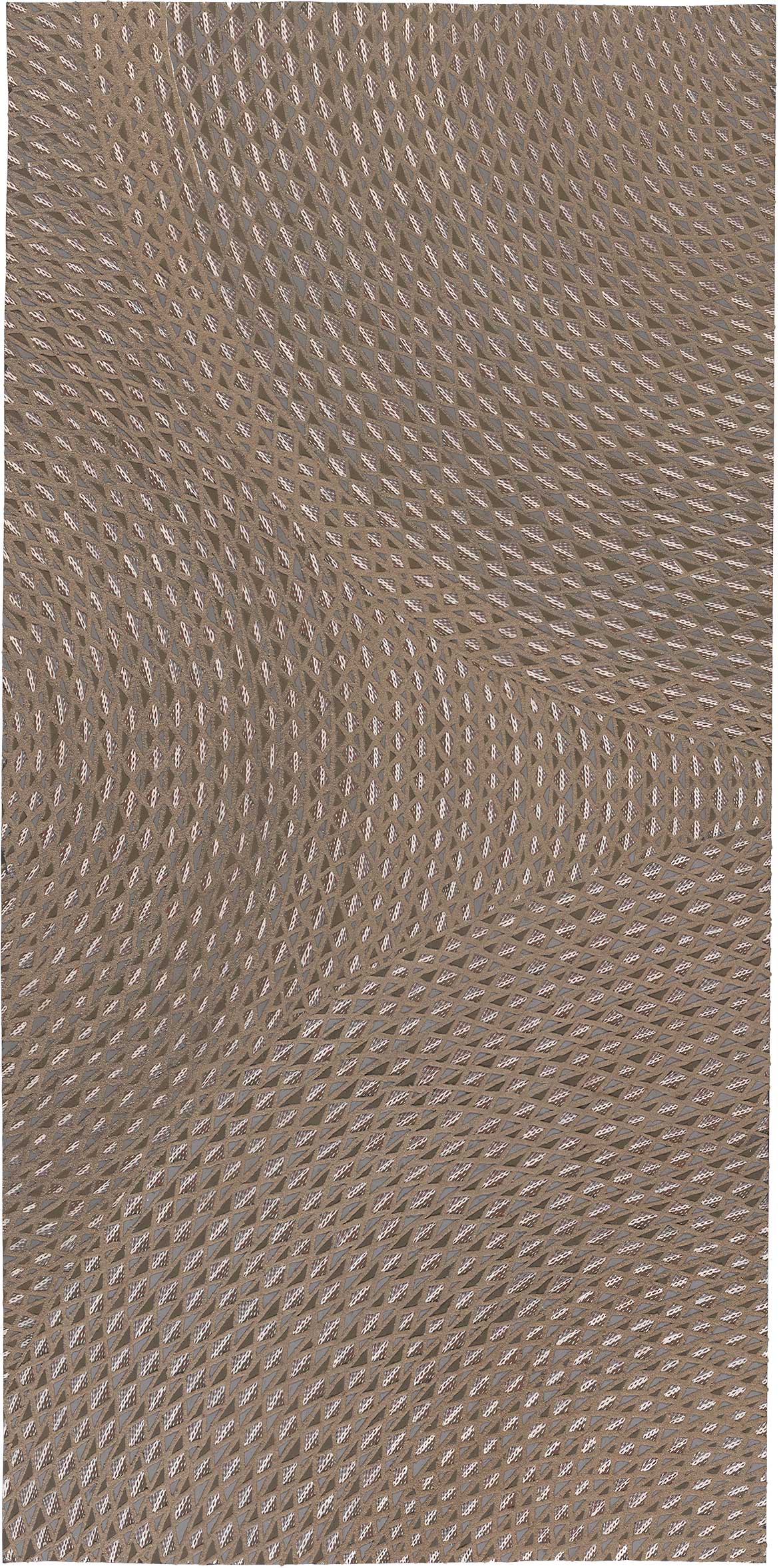

Gunybi Ganambarr, whose family members contributed to those early barks, has grown up with the bauxite mine. As part of a healing process, he has responded to the mine’s unsettling presence by repurposing lengths of its abandoned conveyor belt rubber as an artistic medium. For Ngaymil 2015, he gouged his Ngaymil clan designs into three metres of the dense, black, industrial rubber. In Buyku 2015, sand and natural pigments from his land are layered across its surface in complex, evocative patterns, made permanent with commercial glue. The discarded material becomes a ‘canvas’ on which the young artist reiterates Ngaymil knowledge and reclaims ownership of their land.

Indjalandji-Dhidhanu/Alyawarr artist Shirley Macnamara also reuses the detritus of mining on her family land in western Queensland. Known for her exquisite works of twined spinifex strands, in Cu 2016, she has wound discarded copper wire around a screwdriver to create multiple coils, creating a deeply rounded form to mirror the scarring holes of abandoned copper-mining sites. Loss of vegetation is also a concern, and Macnamara’s work includes an above-country view of the ‘snappy gums’ that grow on top of hillocks there, since levelled through mining. Cu is a reminder that these trees take decades to grow in the hot, dry climate of western Queensland, and their destruction by mining, even long ago, is felt for generations. The artist’s grandson, Nathaniel Macnamara, assisted her in the design and construction of the raw copper-and-wire ‘trees’. Cu tells an all-too-familiar Queensland story of the destructive consequences of unregulated mineral exploration and exploitation, and the resulting destruction of the environment. In a positive response by Macnamara, though, she occasionally includes a particular soft yellow clay found in the abandoned pits to enhance her signature spinifex pieces.

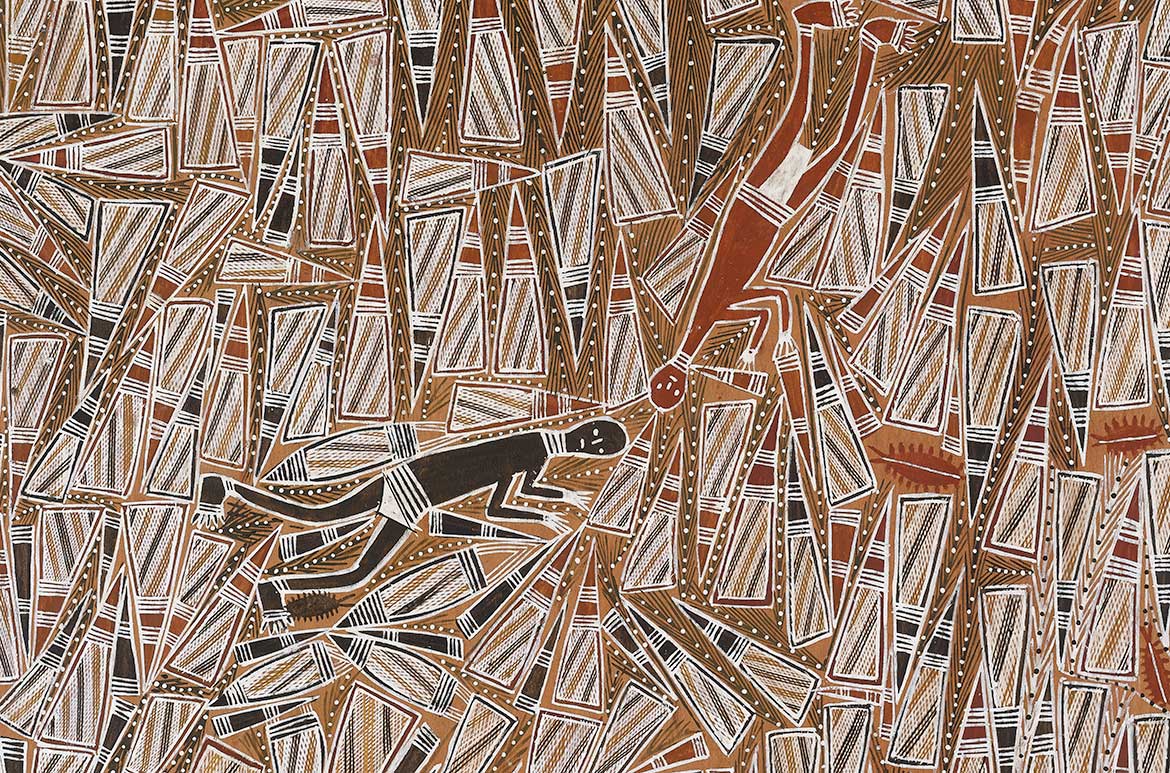

In contrast with these works, Djardie Ashley Wodalpa’s bark painting Ngilipitji stone spearhead quarry 1989 depicts his Wagilag people’s industrious production of ngambi (stone spearheads), demonstrating their control over a clan resource. In a traditional economy based on hunting and gathering food, stone tools were important commodities. As Ngilipitji stone was of very high quality, the clan gained rich rewards and prestige through their astute management of the quarry in accordance with traditional law. They selected only the correct type of stone for removal, and maintained quality control by testing the fragments rigorously before making them into tools. The Wagilag people observed strict protocols in their trade negotiations, which saw the ngambi, wrapped in a protective paperbark djalk (skin), passed over long distances in exchange for vital commodities such as food and sacred ochres.

The Wagilag trace their ownership of the quarry to Aboriginal creation times, when their ancestral spirits first carried ngambi across Arnhem Land to Ngiliptji. Wodalpa’s identity — his madayin (sacred beliefs) and matha (language) — is embedded within his painting of ngambi, which is a personal motif for the artist, intended for transposing onto the body, on bark and on burial poles.

Though the very real impact on Indigenous Australians of the removal of resources simmers below the surface, these works demonstrate that art plays a vital role in promoting discussion, and points the way to a more optimistic future.

Diane Moon is Curator, Indigenous Australian Fibre Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 B Knight (ed.), The Extractive Frontier: Mining for Art [exhibition catalogue], Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne, 2017, p.6.

Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image detail: Djardie Ashley Wodalpa Ngilipitji stone spearhead quarry 1989

#QAGOMA