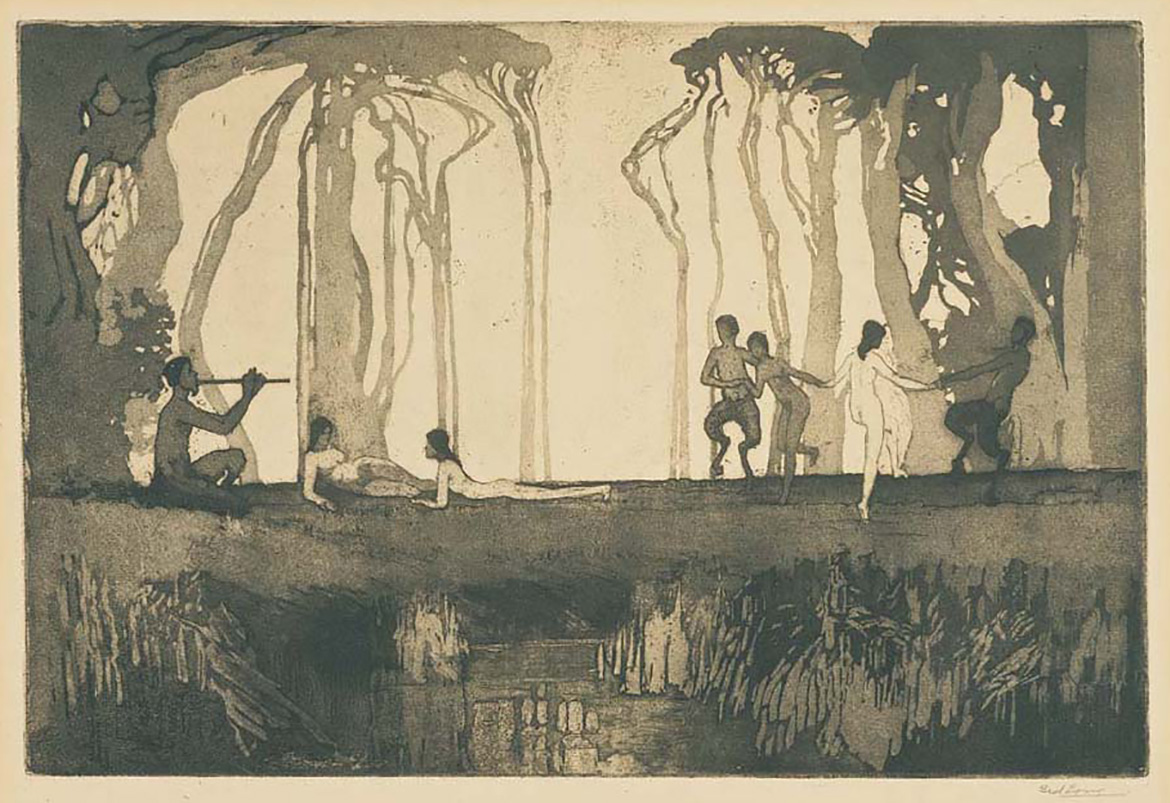

On the face of it, Sydney Long’s (1871-1955) Spirit of the Plains 1897 is an unusual painting to have emerged from the Antipodean colonies in the final years of the nineteenth century. Find out why and delve into its beauty, and the mythology of a burgeoning Australian nation, then go behind-the-scenes as conservation x-rays reveal the numerous compositional changes made by the artist to create one of his most celebrated works.

When Long completed this painting he was 26 years old, and had not, as far as is known, travelled outside New South Wales.1 Originally from the provincial centre of Goulbum, he moved to Sydney in 1888, became a protégé of Julian Ashton, and in 1907 Ashton’s partner at the new Sydney Art School.2

Spirit of the Plains was one of a series of paintings made in Long’s particular decorative style. It was this series that led to his sustained reputation as a major Australian artist, though the works are relatively few in number compared with his total oeuvre. Spirit of the Plains is the least classical of this major group and the most self-consciously Australian. The painting could be read as a nationalist statement in the years leading to Federation, or more reasonably, as a specifically Australian work in a style that was seen to be international.

At the turn of the twentieth century in Australia, an international, particularly a British, context was a desirable comparative measure for Australian art. Spirit of the Plains was exhibited at the Grafton Gallery in London, in an exhibition of Australian art in 1898, and was reproduced in The Studio, the leading English art magazine of the period, in the same year.3 Such international recognition certainly gave the painting an aura of ‘importance’. It is an important painting, but for reasons other than international fame.

RELATED: Conservation projects reveal hidden secrets

SIGN UP NOW: Like to be the first to know? Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest announcements, recent acquisitions, behind-the-scenes features, and artist stories.

Pan, Diana, Ulysses and other assorted gods and heroes were popular subject matter in fin de siècle art in most countries, including Australia.4 The work of popular poets who used classical imagery helped expand knowledge of Greek and Roman myths. Artists such as Norman Lindsay and Lionel Lindsay incorporated mythology into their work, and under these circumstances it was hardly remarkable that an ambitious young artist like Long should appropriate classical subject matter.

Although there is an implied narrative in Spirit of the Plains, this is a myth of Long’s own creation and so it emerges as from a dream: muted tones and shadows help create the impression of ethereal beauty. The trees have been placed in blocks, progressively smaller as a counterpoint to the procession of the girl with her brolgas. They serve to define the space as though it were a theatre stage, with the brolgas dancing across it, the whole piece reduced to one glorious motif. As the critic of the Sydney Mail wrote: ‘It is a poetic and imaginative picture, in soft and myrtle greys, and the idea of the queer Australian bird and its enchantress is very cleverly handled’.5

It was an easy painting for critics of the 1890s to read. The unknown critic of the Daily Telegraph gave the most detailed analysis, and the most favourable:

Mr Sid Long seldom touches canvas without decorating it. His ‘Spirit of the Plains’ this year is no exception. It is essentially Australian, beautifully decorative, and full of feeling. The graceful sweep in the composition, along the group of ‘native companions’, weirdly capering to the soughing of the winds, and culminating in the clump of trees to the left, leaves nothing to be desired. Probably a lot of Mr Long’s candid friends will wish that ‘he paid a little more attention to his figures’, but it is a great question whether the young lady who symbolises the soughing of the wind could be carried a scrap further without injury to the whole effect.6

The general consensus was that Long was creating an authentic Australian myth. Indeed, the nature of Australian mythology was a major concern for the artist. At the turn of the century Long understood the need for his country to develop its own mythological language. As he wrote:

The vagueness of his motives [sic] will render the artist dependent on delicate colour harmonies for the representation of his ideas — ideas which he, perforce, must treat in a symbolic and decorative manner.7

Yet Long’s myth of a bush spirit, leading her dancing birds on an elaborate treble clef formation through the gum treed plains, is based on a European, not Australian, sensibility. Long was a self-consciously modern artist. In Sydney, in the 1890s, modern art and literature meant French Symbolism, English decorative arts, and moonrise. In 1901 the Bulletin’s literary critic, A. G. Stephens, wrote that:

Verlaine’s cult of faded things, extolling the hinted hue before the gross colour, finds a natural home in Australia — in many aspects a Land of Faded Things — of delicate purples, delicious greys, and dull dreamy olives and ochres.8

The modern art magazine, The Studio, had been readily available in Sydney since its initial publication in 18939 and the artist who was most admired by many Australian artists, albeit at a distance, was the French symbolist, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. His set piece paintings with their shallow frieze-like spaces quoted austere archaic classicism.

It is that sense of space without depth that is used by Long in Spirit of the Plains, but he subdues the vertical strokes of the trees, pushes them back in a receding rhythm, and instead places across his stage a pubescent nymph, piping her birds in an elaborate dance. She is not yet an angel, the moon rises to the side of her head, not into a halo as in the later etching and painting, but her features are defined in shadow.10 Bearing in mind the awkwardness of Long’s attempts at figure painting, the critic of the Daily Telegraph probably had a point when he criticised Long’s drawing.

After over a century Spirit of the Plains remains one of the great beauties of Australian art. The girl leads her captivated birds in an elegant dance across a moonlit plain. The mood of twilight magic is created by the oddly satisfying tonal relationships of greys, blues, and pink-flushed pastel.

The populating of the Australian bush with nymphs and gods served to develop a mythology of the burgeoning nation. As opposed to many traditional views of the landscape, which depicted it as a site of industry or pure majesty, Long created a lyrical vision, inspired by his European contemporaries, but achieved with Australian imagery.

Delve into the secrets of ‘Spirit of the Plains’

Go behind-the-scenes with Anne Carter, Conservator, Paintings at QAGOMA and watch as she delves into its secrets. In 1897, the year it was painted, Sydney Long’s Spirit of the plains was met with critical acclaim for its compositional elegance. The viewer then, and now, would have little idea of the major compositional changes made by the artist as he realised one of his most celebrated works.

Edited extract from ‘Dancing across the landscape: Sydney Long Spirit of the Plains‘ from Lynne Seear and Julie Ewington (eds). Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998. Dr Joanna Mendelssohn was Senior Lecturer in Art History at the College of Fine Arts, University of Sydney.

Endnotes

1 Long’s birth was registered on 17 November 1871, but according to his birth certificate he was born on 20 August 1871. His father is recorded as having died on 11 February 1871, However, for many years Long maintained that he was born on 15 November 1872, changing this to 15 August 1878 in the later years of his life.

2 Long’s father died before his birth, so Long was not born to affluence. Throughout his life he was concerned with the need for some kind of acceptance from whatever establishment he was dealing with.

3 Spirit of the Plains was exhibited at the ‘Exhibition of Australian Art in London’, Grafton Gallery, London, 1898, cat. no. 29, and was reproduced In The Studio, London, XIII, no.62, May 1898, p.269.

4 See Deborah Edwards, Stampede of the Lower Gods: Classical Mythology in Australian Art, 1890s-1930s, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1989.

5 ‘The Latest Art Exhibition’, Sydney Mail, 9 October 1897, p.765.

6 ‘Society of Artists Exhibition’, Daily Telegraph, Sydney, 2 October 1897, p.10.

7 Sydney Long, ‘The trend of Australian art considered and discussed’, Art and Architecture, January 1905.

8 Quoted in Bernard Smith, Australian Painting 1788- 1960, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1962, p.101.

9 The Art Gallery of New South Wales Library appears to have subscribed to The Studio since it was first published, and Angus & Robertson’s bookshop apparently distributed Studio publications.

10 Long reworked some of his Australian successes when he was in London. The 1914 version of Spirit of the Plains in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, is one of these, as are the various etchings and aquatints of Spirit of the Plains, executed in 1918.

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read about your Australian Collection / Hear artists tell their stories / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image detail: Sydney Long Spirit of the Plains 1897

#SydneyLong #QAGOMA