Celebrated Australian artist eX de Medici’s career spans 40 years with the artist’s central concerns including the fragility of life, global affairs, greed and commerce, and the universal themes of power, conflict, and death. Here we delve into two companion works — The theory of everything 2005 and Live the (Big Black) Dream 2006.

eX de Medici ‘The theory of everything’

The epigraph… ‘[The tortoise] was still quite motionless and he felt it with his fingers; it was dead. Accustomed, no doubt, to an uneventful existence, to a humble life spent beneath its poor carapace, it had not been able to bear the dazzling splendour thrust upon it, the glittering cope in which it had been garbed, the gems with which its back had been encrusted2, drawn from Huysmans’s nineteenth-century novel about eccentric aesthete Jean des Esseintes, whose fortune permits him to indulge his every fancy, is a potent allegory for the profligacy of modern life and humanity’s propensity to destroy the natural world, key themes in eX de Medici’s 40-year practice. In this vignette, Des Esseintes is so consumed by the desire to obtain an object that will serve as a foil for the colours in his Persian carpet that he has a tortoise gilded and bejewelled, only to find that the creature has died under the weight of its embellishments.

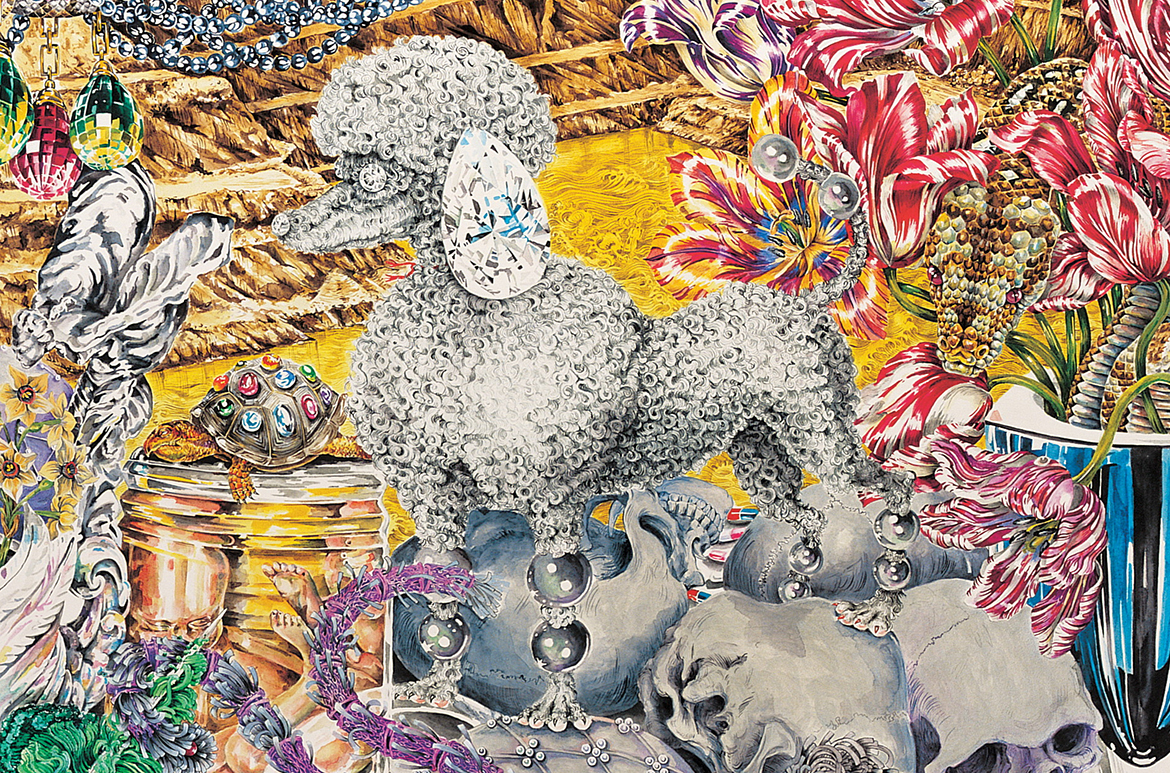

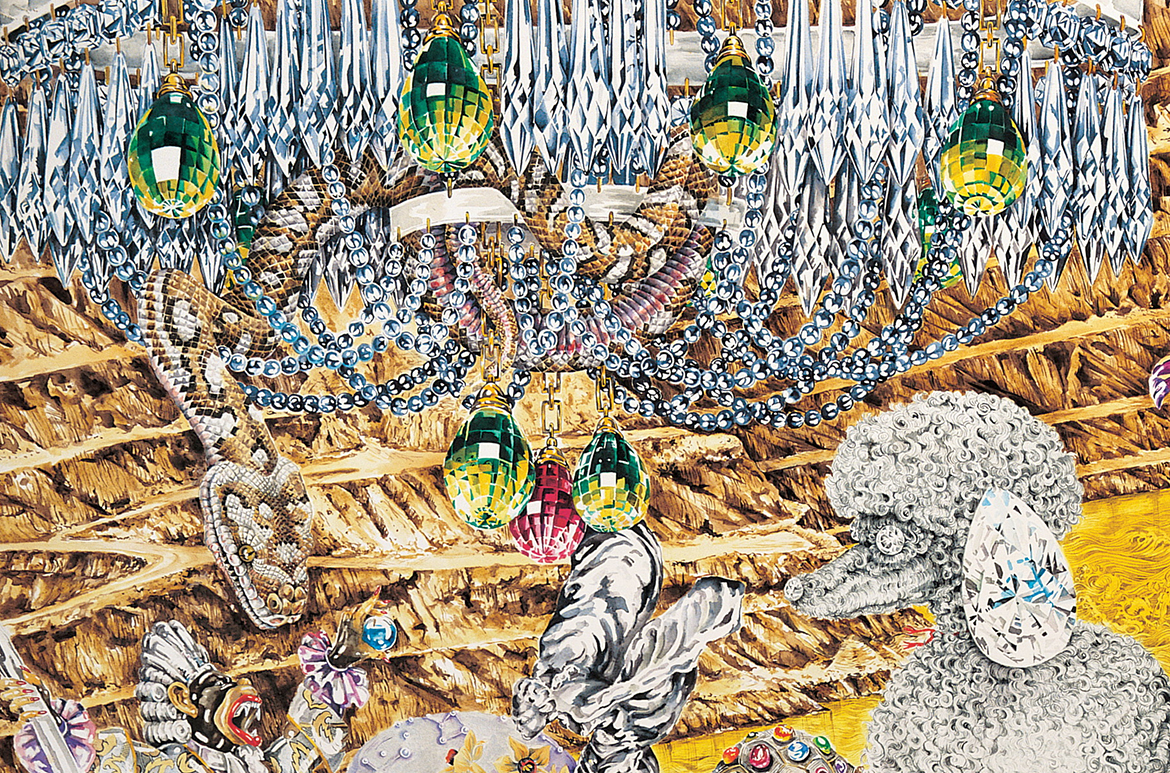

The anecdote’s significance to de Medici is evident in her study Des Esseintes’ Shame 2005 (Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra) and the watercolour that it informs, The Theory of Everything 2005 (illustrated). In the latter painting, a tiny, adorned tortoise (detail illustrated)) nestles among other icons of human folly and excess: a notional, diamond-studded poodle (detail illustrated) — the dog was originally bred as a retriever and clipped, so in freezing waters its thick coat would protect its vital organs and not impede it, however, the grooming took on a purely decorative function in eighteenth-century France, mimicking the preposterous hairstyles of the day; variegated Semper Augustus tulips (detail illustrated) — a reference to ‘tulipmania’, the earliest documented financial boom and bust, which beset Holland in the mid seventeenth century, when bulbs that the Dutch East India Company imported from the Ottoman Empire were bartered for exorbitant and unsustainable prices; the chandelier from a Tsar candelabrum (detail illustrated), designed in 1903 by Compagnie des Cristalleries de Baccarat, the French glassworks synonymous with luxury; and a cut crystal vase of narcissus flowers being sniffed by the ‘Spirit of Ecstasy’ figurine from the bonnet of a Rolls-Royce (detail illustrated), to name but a few.3 Together, these cryptic elements, which traverse cultures and periods, tell a sorry story.

It is no coincidence that such symbols of intemperance intermingle with human skulls, exploded ammunition, a Smith & Wesson M&P pistol, and a moth skewered by a hatpin that has caused corrosive verdigris to sprout from its innards (detail illustrated). These emblems of death — and the transient paraphernalia that adorn them — are de Medici’s version of a seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas, a form of still-life painting encoded with signs of mortality, such as skulls, hourglasses and flowers in full bloom. Also referred to as memento mori, Latin for ‘remember, you must die’, these paintings — both historic and de Medici’s contemporary renderings — are warnings to beware the allure of worldly possessions lest they engender your demise. De Medici’s modern-day fables go further to implicate the human hands at work behind such extravagances, and to prophesy the perils of disregarding the fragility of life and exploiting the environment. The background of The Theory of Everything features the Ranger Uranium Mine in the Northern Territory, which de Medici explains:

. . . is in the middle of [Kakadu] national park. On traditional lands. And it’s a gigantic, filthy hole, where everything withers and dies. So [it is] the idea of wealth at any cost, and acquisition at any cost. At the cost of the future, at the cost of the land, at the cost of human and animal and plant health . . . it’s a hideous critique of what’s going on.4

eX de Medici ‘Live the (Big Black) Dream’

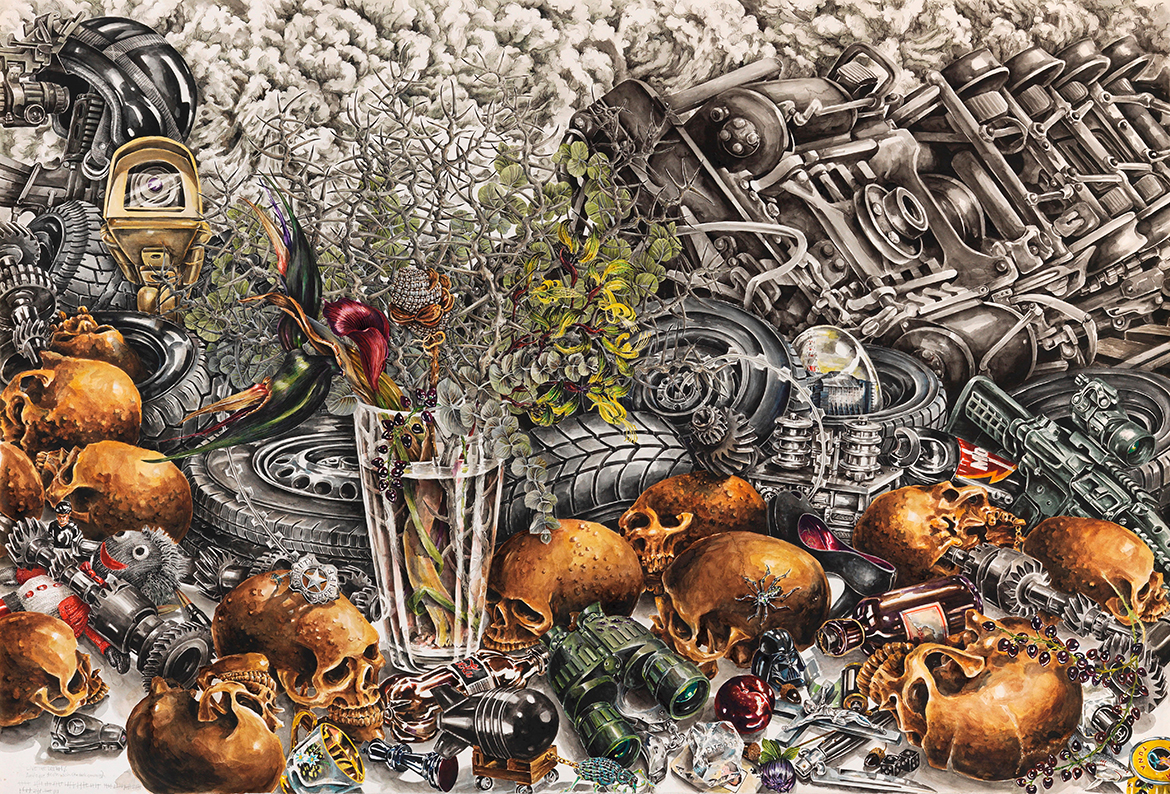

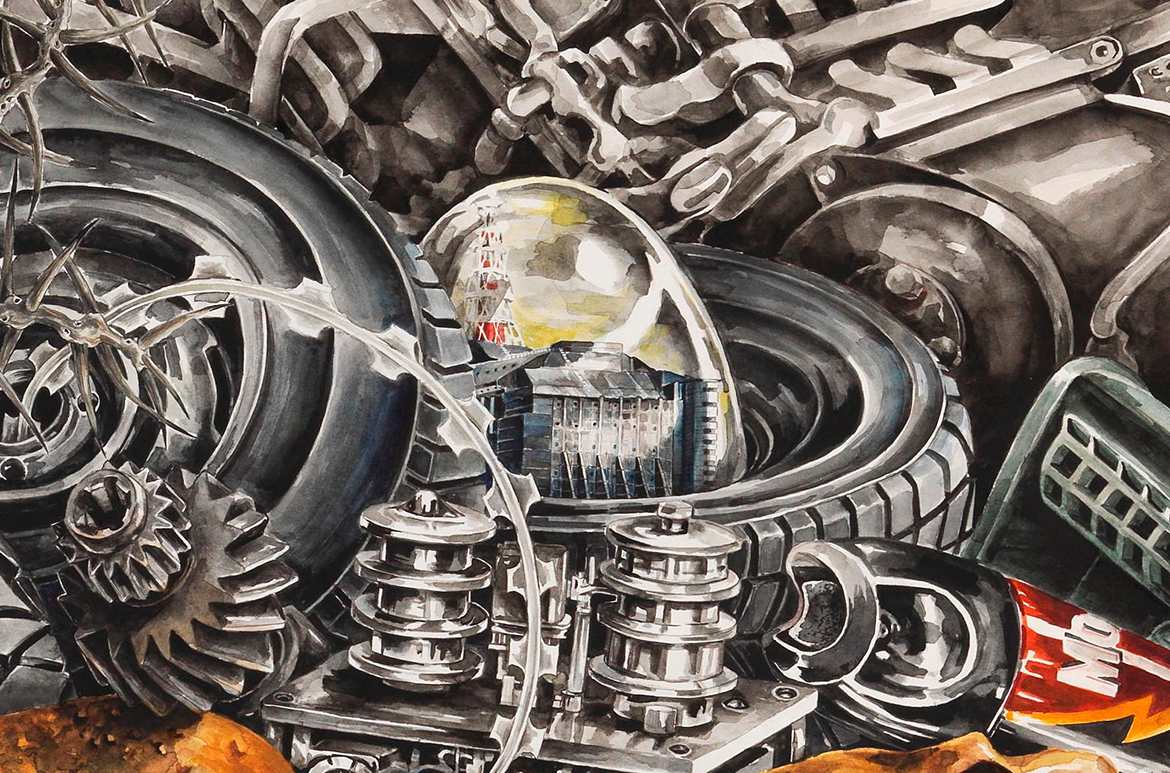

The watercolour is a microcosm of all that has driven the artist’s diverse and far-reaching practice. Its companion piece, Live the (Big Black) Dream 2006 (illustrated), represents the culmination of the intemperate appetites that the earlier artwork decries — a train wreck waiting to happen, which, in an irony that the artist has lamented, foretold the Global Financial Crisis that unfolded from mid 2007.5 ‘Big Black’ sees the capitalist system derailed in a pile-up of grand proportions and, like many of de Medici’s artworks, is laden with coded symbolism, including menacing motifs that signify the base impulses to which humanity is prone.6 The detritus includes skulls that the artist, who is also a veteran tattooist, regards as ‘the best memento mori image there is’; a bottle of poison (detail illustrated); the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in a snow dome (detail illustrated); an AR-15 machine gun — discomfortingly referred to as ‘America’s rifle’; and a miniaturised image of the atomic bomb that the United States (US) dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki to end World War Two, being towed by a weevil, a tiny but destructive insect that executes its invasive behaviours by stealth (detail illustrated).7 The idea of clandestine acts hiding in plain sight is underscored by the presence of a CCTV camera, a reference to the surveillance that we are increasingly and, often, willingly subjected to in this networked age, and a twin motif to the satellite in The Theory of Everything. The deputy sheriff’s badge plunged into a skull (detail illustrated) in the foreground of ‘Big Black’ is a veiled reference to then Prime Minister John Howard and his eagerness to follow US President George W Bush down the road of fiscal recklessness and into unwinnable wars.8

These two watercolours form part of a series of ‘big pictures’ that paint a bleak vision of our world. Together, these artworks represent an extended metaphor through which De Medici dissects the mess that humanity — and, in particular, human industry — has made of the planet, denouncing the devastating effects of the Anthropocene, the geological age in which our species has impacted itself and the Earth.

Samantha Littley is Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA.

This edited extract was originally published in eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, 2023

Endnotes

1 Essay subtitle ‘Something wicked this way comes’ from William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Bernard Lott (ed.), Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1958, p.145; Act IV, Scene I, 45.

2 Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature, trans. Margaret Mauldon, Oxford University Press, New York, 2009, p.43; first published as À Rebours, Charpentier et Cie, Paris, 1884.

3 See QAGOMA, ‘APT5 / eX de Medici discusses her art practice and “The Theory of Everything”’ video; and ‘A short history of poodle grooming’, Pedigree, <pedigree.com/article/short-history-poodle-grooming>, both viewed September 2022. ‘Tulipmania’ was a real, though exaggerated, phenomenon that is the subject of a book by Anne Goldgar, Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge inthe Dutch Golden Age, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2007. See also Lorraine Boissoneault, ‘There never was a real tulip fever’, Smithsonian Magazine, 18 September 2017, <smithsonianmag.com/history/there-never-was-real-tulip-fever-180964915/>, and Erhan Afyoncu, ‘Tulip mania: The 17th century bitcoin craze’, Daily Sabah, 2 March 2018, <dailysabah.com/feature/2018/03/02/tulip-mania-the-17th-century-craze>, both viewed October 2022. The striations on the Semper Augustus tulip are caused by a mosaic virus, the Tulip breaking virus (TBV), with the Dutch prizing the flower for its beauty, ‘without knowing it was the result of a viral infection’; see ‘Tulip breaking virus’, ScienceDirect, <sciencedirect.

com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/tulip-breaking-virus>, viewed October 2022. The candelabrum depicted in the watercolour is one of a pair manufactured in 1911, Tsar, pair of candelabra (Acc. D22.1-2-1982), now held by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV); telephone conversation with the artist, 14 June 2022. The NGV’s candelabra once graced the

proscenium of the auditorium of Melbourne’s Capitol Theatre, which was designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. See Christopher Menz, ‘BACCARAT Tsar candelabrum’, in Christopher Menz and Margaret Legge, with contributions by Anna Nieuwenhuysen, Decorative Arts in the International Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2003, p.96. The candelabra take their name from the Russian Tsars Alexander II and Nicholas II, and other members of the Romanov family, who, from 1867, commissioned Baccarat to make chandeliers and other works of decorative art; see ‘A monumental pair of French cut and molded-crystal seventy-nine-light candelabra’, Christie’s,

<christies.com/en/lot/lot-5985087>, and ‘What the expert looks for . . . No.1 – Baccarat chandeliers’, Christie’s, <christies.com/features/Expert-tipson-Baccarat-chandeliers-9775-1.aspx#:~:text=A%20brief%20history%20

of%20Baccarat&text=In%201764%20King%20Louis%20XV,still%20are%2C%20synonymous%20with%20luxury>, both viewed September 2022.

4 QAGOMA, ‘APT5 / eX de Medici discusses her art practice and “The Theory of Everything”’, viewed September 2022. In 2009, it was revealed that the mine, owned by ASX-listed Energy Resources of Australia (ERA), which is majority-owned by mining giant Rio Tinto, was leaking contaminated water into a tailings dam and, in 2013, one million litres of radioactive slurry was

released by a burst leach tank, leading Mirrar native title holders to insist that mining operations in the area be wound up and that ERA complete remediation of the site by 2026, as well as refraining from reopening operations at nearby Jabiluka. This work has been delayed as the result of various corporate disputes, including Rio Tinto’s attempt to assume more than 95 per cent of the shares in ERA by becoming the sole funder of the remediation work. In October 2022, an update on this commercial wrangling appeared in the Guardian, who reported that ERA’s directors had offered their resignations from the board because Rio Tinto, who now owns 86 per cent of shares in the company, has refused to recommence mining at the Ranger and Jabiluka sites, throwing ‘into limbo efforts to raise up to $2.2bn needed for the remediation of Ranger — work that is already suffering from large cost blowouts and lengthy delays’. See Ben Butler, ‘Directors of firm responsible for clean-up at Kakadu uranium site will resign amid fight with Rio Tinto’, Guardian, 3 October 2022,<theguardian.com/business/2022/oct/03/rio-tintocalls-for-board-resignation-over-kakadu-uranium-site-clean-up>, viewed

October 2022.

5 In 2006, these artworks featured in ‘The 5th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT5), the first Triennial that spanned both the Queensland Art Gallery and the newly built Gallery of Modern Art.

6 For a discussion of humanity’s predisposition towards violence, see David Livingstone Smith, The Most Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War, St Martin’s Press, New York, 2007; for example, Livingstone Smith suggests that ‘violence has followed our species every step of the way in its long journey through time. From the scalped bodies of ancient warriors to the suicide bombers in today’s newspaper headlines, history is drenched in human blood’, p.8.

7 eX de Medici, ‘APT5 / eX de Medici discusses her art practice and The Theory of Everything’, viewed September 2022. For an exposé on the AR-15, see Ali Watkins, John Ismay and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, ‘Once banned, now loved and loathed: How the AR-15 became “America’s Rifle”’, New York Times, 3 March 2018, <nytimes.com/2018/03/03/us/politics/ar-15-americas-rifle.html>, viewed October 2022.

8 Leigh Sales and James Elton, ‘Afghanistan not entirely a failure, says John Howard, who first committed Australian troops’, ABC News, 18 August 2021, <abc.net.au/news/2021-08-18/john-howard-afghanistan-war-not-a-failure-730-interview/100388644>; Ben Doherty, ‘John Howard defends Iraq war, saying it was “justified at the time”’, Guardian, 7 July 2016, <theguardian. com/uk-news/2016/jul/07/john-howard-chilcot-sending-troops-iraq-warjustified-at-the-time->, both viewed November 2022.

‘eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness’ in 1.2 and 1.3 (Eric and Marion Taylor Gallery) was at GOMA from 24 June until 2 October 2023. ‘Beautiful Wickedness’ offered opportunities for dialogue with ‘Michael Zavros: The Favourite‘ presented in the adjacent gallery 1.1 (The Fairfax Gallery) and 1.2.

#QAGOMA