For Gerhard Richter, history, painting and photography are intimately linked, we therefore have listed five things that help understand one of the world’s leading and most influential living artists.

5 things to know about Gerhard Richter

1. History

Born in 1932, Gerhard Richter has been making art for as long as many of us have been alive. He was 12 years old when his city of birth, Dresden, was bombed by allied forces during World War Two. He and his mother were living in a rural town outside of Dresden at the time. When he returned to Dresden in 1951 to study at the Dresden Art Academy, more than five years after the end of the war, the city was still in ruins.

‘There were only piles of rubble to the left and right of what had been streets’. Every day we walked from the academy to the cafeteria through rubble, about two kilometres there and back’

Such events formed part of Richter’s early life and were to inform his art throughout his career. The two paintings, Uncle Rudi 1965 and Aunt Marianne 1965 are based on photographs from a family album that Richter took with him when he fled East Germany in 1961. They relate to his own family during the war years and their tragic history.

SIGN UP NOW: Be the first to know. Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest announcements, acquisitions, and behind-the-scenes features.

RELATED: Five reasons to be in awe of Gerhard Richter

RELATED: Gerhard Richter’s remarkable command of style and genre

DELVE DEEPER: Read more about Gerhard Richter

2. Freedom

Freedom can often require leaving something or someone behind. It comes at a price.

When Gerhard Richter left East Germany in March 1961 he had to do it covertly. He travelled as a tourist alone, first to Moscow and then to Leningrad. On the return the train stopped at West Berlin where Richter stashed additional suitcases he had brought with him, before returning to Dresden to collect his wife, Marianne Eufinger, known as ‘Ema’.

The borders between the Communist, German Democratic Republic and West Germany were being sealed — just months away from the erection of the Berlin Wall that was to divide the two Germanys for 28 years until its demolition in 1989. Trains and subways were still operating between the Soviet-occupied East and West Berlin making it the last remaining link to the free west.

Richter had a friend drive himself and Ema from Dresden to East Berlin where they boarded a train (without suitcases, which drew suspicion) for the western sector of Berlin where they registered as refugees. Between 1958 and 1961, 700,000 people fled East Germany for the West. Richter’s parents were never allowed to leave East Germany or to visit their son. They died in 1967 and 1968.

Richter was nearly thirty years old when he left East Germany. In Dusseldorf, where he studied and eventually taught, he began to number his works and reject almost everything he had done that was associated with his previous life. But your past never leaves you.

Richter has never been defined by a specific style and has used a variety of materials, techniques and methodologies during his career, like many young artists today. This represented a creative freedom for Richter who had spent more than a decade as a student and young apprentice in East Germany painting murals and making art within the narrow socialist confines of the German Democratic Republic. His academic training in Dresden did however, equip him with skills and technical facility that found expression later in still life paintings, portraits and landscapes.

3. Memory

The late writer, critic and essayist, John Berger once asked the question,

‘What served in place of the photograph; before the camera’s invention? The expected answer is the engraving, the drawing, the painting. The more revealing answer might be: memory’.

Photographs have been central to the art of Gerhard Richter. One of the few things he took with him to West Germany was a family album of photographs – some of which became the basis for later paintings. After arriving in West Germany, Richter began to systematically collect photographs, clippings from magazines and books and eventually took many thousands of his own photographs. This accumulation of photographic and reproduced images became the basis for his vast life-long project called Atlas.

Richter’s Atlas includes an extraordinary range of imagery, from harrowing images of the Holocaust to tender images of his children. It was created at a time before digital photography became so common place — when photographs were understood to be a trace of something or some time. Like footprints, fossils, markings on a tree — traces of what has been. Digital technology has changed photography from something we once looked at and reflected upon to something we Send. Once they were an index of memory, now we distribute them in their millions, and forget them.

Watch our time-lapse as we install the ATLAS compendium comprising some 400 panels personally selected by the artist from thousands of clippings, photographs and source images.

4. Beauty

Gerhard Richter has stated that beauty is a ‘dangerous word’. He was thinking about how the Third Reich associated beauty with the notion of racial purity — which culminated in obscene evil and violence. He has also said that, ‘beauty is the opposite of destruction, disintegration and damage’. Today ‘beauty’ is a loaded term. It is often considered obsolete in relation to art. In some instances it is understood to be ‘discriminatory’. But the word is still used, often and sometimes carelessly. Beauty can be found in a song, a thankyou note from a friend, a reflection on still water. Beauty can still be dangerous and it often keeps company with sadness.

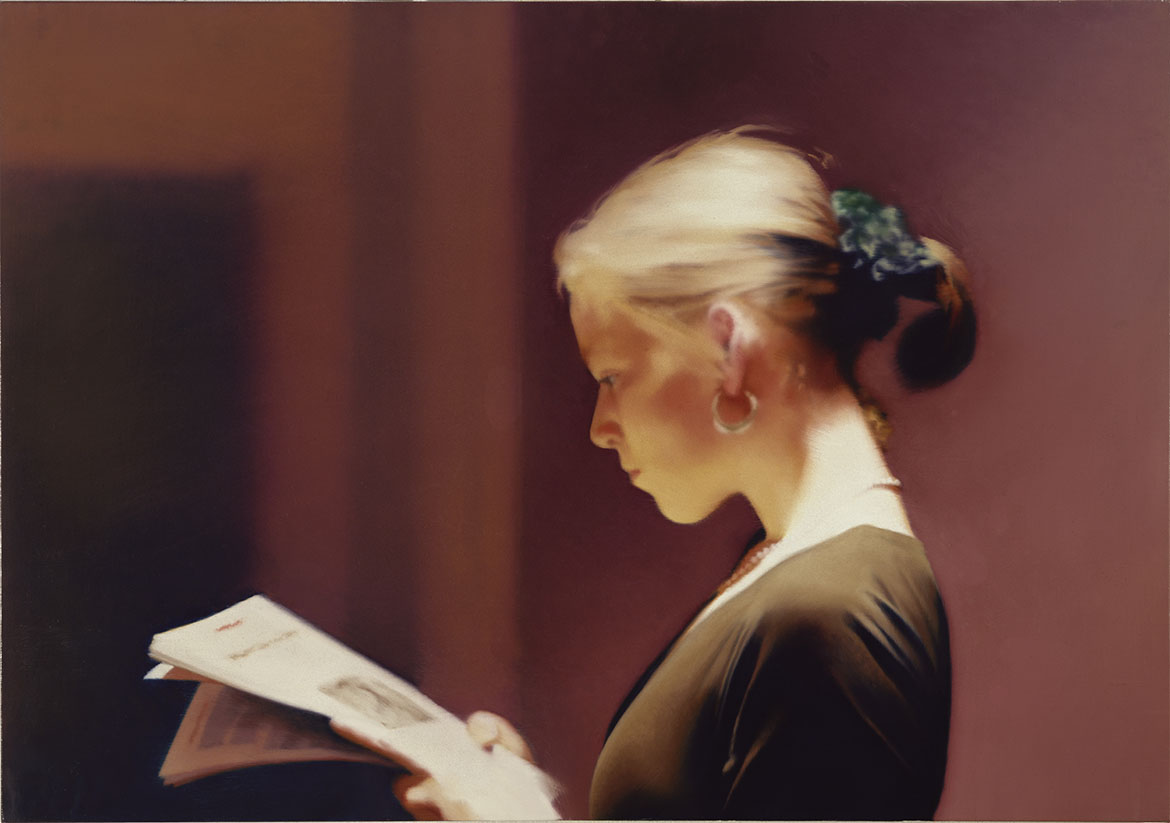

Richter finds beauty in nature — an exquisite orchid, the light on the side of his wife’s hair. He has also described his monochrome grey paintings as possessing beauty. Perhaps beauty is not something we can ‘possess’ but only recognise.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow, Curatorial Manager, International Art, QAGOMA introduces you to her favourite work in ‘The Life of Images’.

5. Reality

A common response by many thousands of people following the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11 2001 was incomprehension. The ‘reality’ of the situation was almost impossible to accept or understand. The event was immediately and constantly compared to a movie. The French theorist, Jean Baudrillard commented that the repeated broadcasts of the footage served ‘to multiply it to infinity and, at the same time, they are a diversion and a neutralization”—the more we see the events, the less comprehensible they become.’

Baudrillard was interested in the way that photographic media affect our perception of reality and the world. He believed that the overwhelming amount of imagery that we consume in the forms of television, film and video, computer games and the internet results in a ‘hyperreality’, a simulation of the real.

Gerhard Richter said that, ‘Photography has almost no reality; it is almost a hundred per cent picture. And painting always has reality: you can touch the paint; it has presence; but it always yields a picture – no matter whether good or bad. … I once took some small photographs and then smeared them with paint. That partly resolved the problem, and it’s really good – better than anything I could ever say on the subject’.

David Burnett is former Curator, International Art, QAGOMA

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read more about Australian art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

‘Gerhard Richter: The Life of Images‘ was at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) from 14 October 2017 until 4 February 2018 and featured over 90 works from six decades of Richter’s career. Drawn from major museum and private collections, as well as Richter’s own personal archive, the exhibition provided a unique opportunity to view the diverse range of his exploration of painting.

See the world from a new perspective at QAGOMA. Together, the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) and Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) offer compelling experiences that will move and surprise you. Australia

Featured image detail: Gerhard Richter, 1970 © Gerhard Richter 2017

#GerhardRichter #QAGOMA