The influence of Japanese aesthetics in France during the nineteenth century proved pivotal to a number of modern art movements. To celebrate the artistic intersections between France and Japan, the Gallery presents screens and decorative ware alongside impressionist landscapes and modern works.

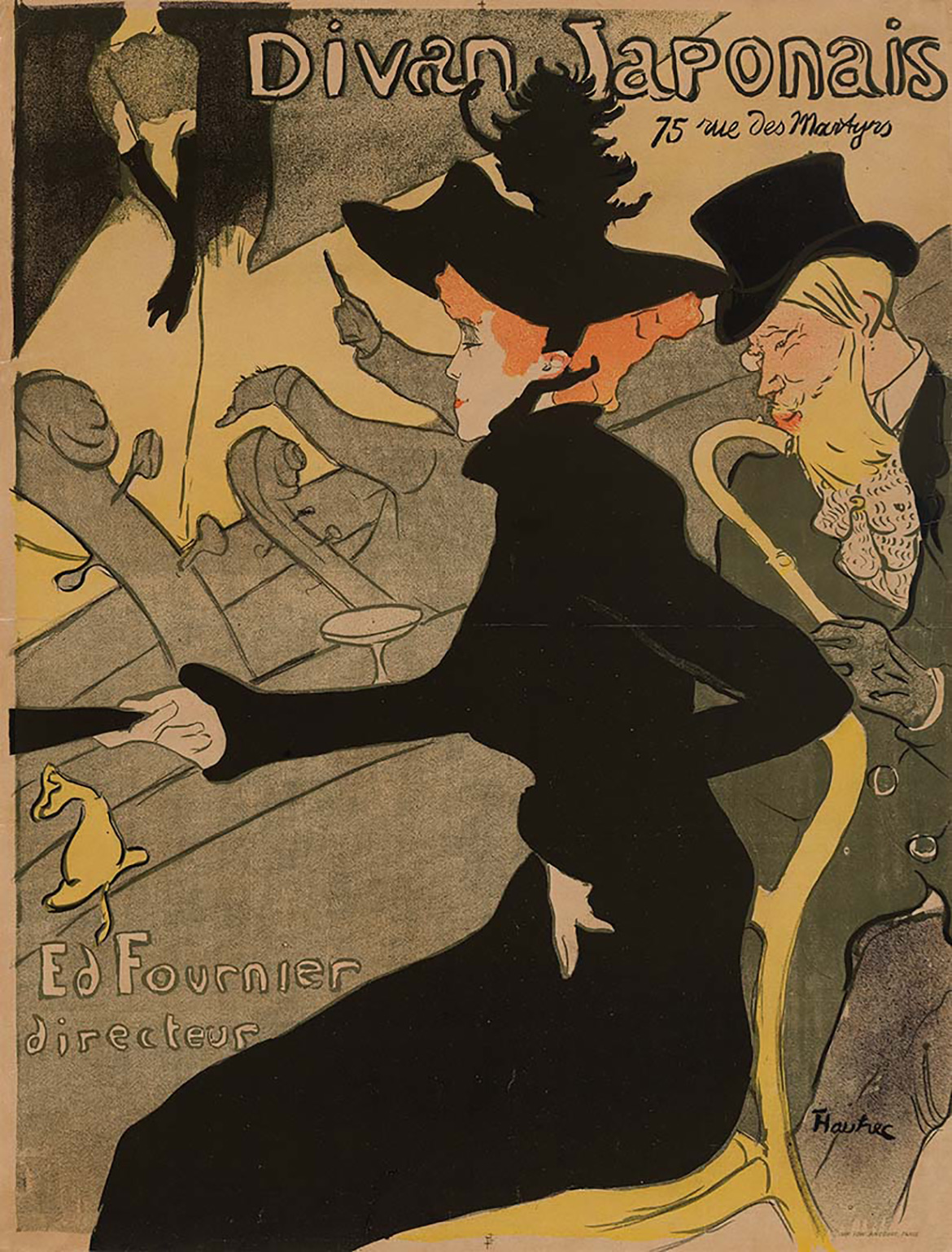

Coined in 1872 to describe the influence of Japanese art on European artists and designers, the word ‘Japonisme’ was first used by French critic, collector and printmaker Philippe Burty. Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists during this period, and the country’s aesthetic deeply affected the European art of the late nineteenth century — from composition, technique and subject, to the inclusion of Japanese ceramics, prints and textiles in European paintings, and objects decorated with Japanese designs.

After some 250 years of embargo, trade between Japan and France, Britain, Russia and the United States resumed after the formalisation of treaties and diplomatic relations in 1854–58. Japanese woodblock prints, textiles, ceramics, screens, netsuke and objets d’art began to appear in European markets from the 1860s and were highly desirable. Major exhibitions in Paris, such as the 1867 Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair), brought Japanese art and design to the attention of a broader public, while institutions such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France added Japanese art to their collections. In the avant-garde city of Paris, the effect on art and design was so considerable that it contributed to the development of new aesthetic movements, including Impressionism, Post- Impressionism and Art Nouveau in France; while in Britain, it informed the Aesthetic style.

The influx of Japanese artworks in Europe coincided with a period of experimentation that saw European artists taking new artistic approaches to their work. Ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’) woodblock prints, in particular, were notably influential on French artists associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, who were attracted to their bold style, and recognised the dynamic and novel way in which they depicted scenes of ordinary life. The aesthetic that most challenged European convention was the alternative it proposed to perspectival space: ukiyo-e were characterised by cropped, asymmetrical compositions, defined outlines and flat areas of colour. European artists were excited by the prints, and by the new technology of photography — only recently invented — for their ability to capture the fleeting, casual moments of life otherwise absent from formal academic painting.

SIGN UP NOW: Be the first to know. Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest announcements, acquisitions, and behind-the-scenes features.

Many artists of the time became keen collectors of Japanese art — Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Henri Toulouse- Lautrec, Edouard Vuillard, Vincent van Gogh and American expatriate Mary Cassatt among them. The magazine Le Japon Artistique, published by German-born French art dealer Siegfried Bing, was highly influential, and reproduced many of the major prints by ukiyo-e artists. Japanese objets d’art and modes of dress particularly enchanted James Tissot, Claude Monet, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who depicted Western models in elaborately embroidered kimonos, and they also included Japanese ceramics and prints, almost like props, in the composition of their works. Monet created his garden at Giverny in the Japanese style, and decorated the interior of his house with woodblock prints and Japanese ceramics. More subtly, the Japanese printmakers’ use of asymmetrical compositions and unusual perspectives also influenced these artists.

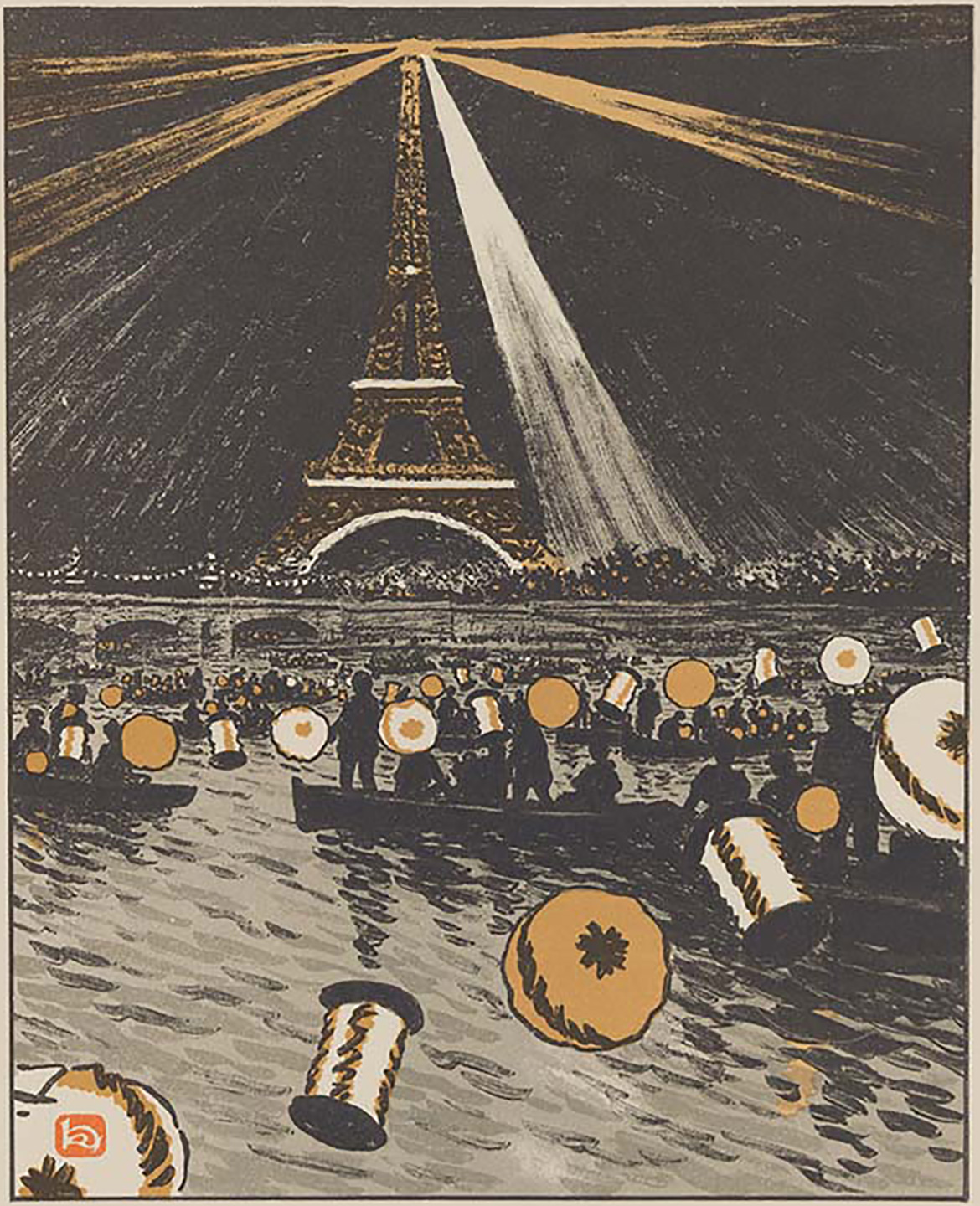

Henri Rivière’s lithographic series Les Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel (Thirty-six views of the Eiffel Tower) 1902 is regarded as one of the finest examples of Japonisme. Visible from every quarter, engineer Gustave Eiffel’s tower dominated Paris’s skyline following its construction for the Exposition Universelle in 1889: for Rivière, who climbed and photographed the tower just prior to its completion, it represented a completely new type of spatial and visual beauty. When viewed from within, the structure’s massive iron girders created abstract patterns against the sky. When viewed from the ground, the tower was at once an omnipresent backdrop to daily Parisian life and an international icon of modernity.

Modelled on the masterful collection of woodblock prints by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), titled ‘Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji’ c.1830–32, Rivière’s ‘views’ show the artist’s captivation by the composition of traditional ukiyo-e. The subdued colour palette of nineteenth-century manga (a term Hokusai coined to describe his collections of sketches) enabled Rivière to capture the monumentality of the Eiffel Tower.

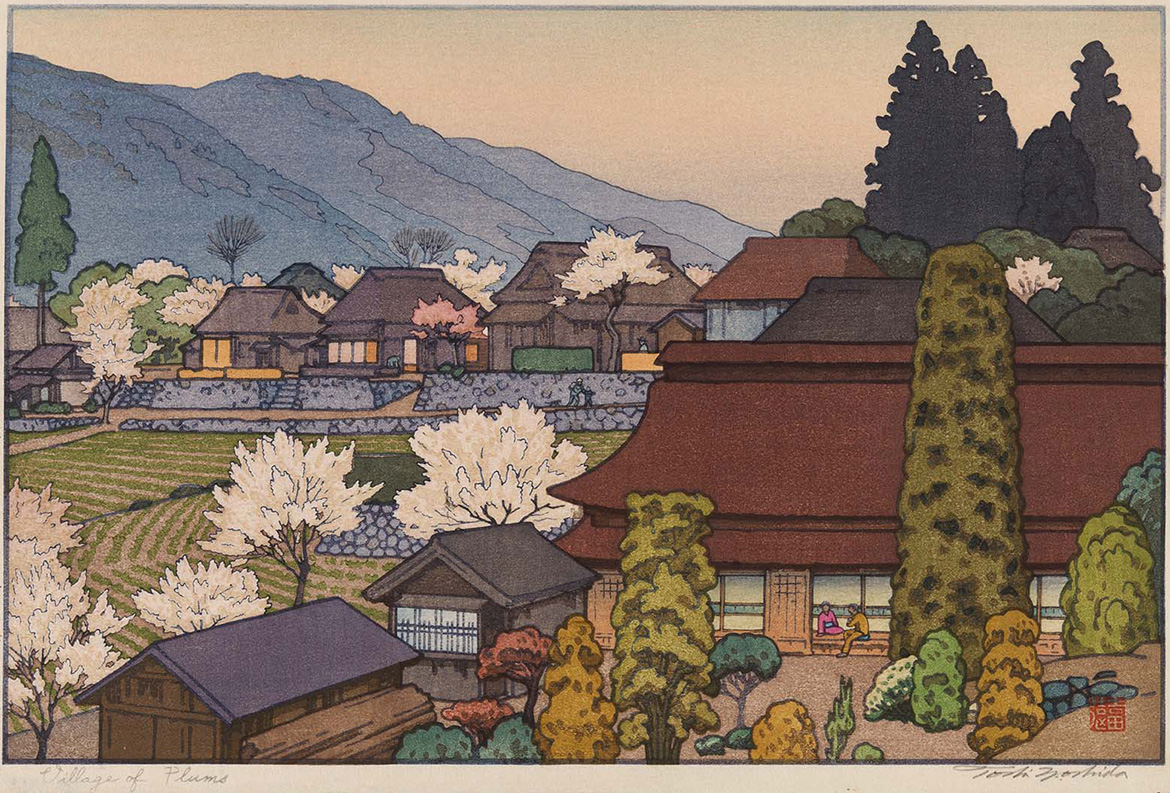

Just as Western artists were finding inspiration in Japanese art, Japan was opening to the West. Shin-hanga (literally ‘new prints’) prints show the influence of impressionist techniques and colour ranges, and point to the two-way relationship between the art of the East and West at the turn of the twentieth century. Toshi Yoshida’s prints are associated with the Shin-hanga movement, which emerged in Japan in the 1920s. Stylistically different from traditional ukiyo-e works, their large areas of unbroken colour indicate the influence of Impressionism from the late nineteenth century.

For many European nations, including France, the late nineteenth century was a time of expanding frontiers. Colonisation and imperialism were the more negative aspects of this outward gaze, but in the arts, the era’s expansiveness enabled artists to look beyond the Greco–Roman principles of European art and develop new modes and styles of representation. Affecting painting, printmaking, sculpture and the decorative arts, Japonisme was a formative influence on the various movements that would one day constitute Modernism.

Abigail Bernal is Assistant Curator, International Art, QAGOMA.

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read more about the Australian Collection / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image detail: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Divan Japonais 1892–93

#QAGOMA