Join us at the Australian Cinémathèque, Gallery of Modern Art for a special one-day screening and In Conversation event with award-winning independent Australian animator, Dennis Tupicoff to celebrate the release of his new film The Only Photograph of Emily Dickinson, American Poet 2023.

Born in Ipswich and growing up in the Brisbane suburb of Darra, Tupicoff is an internationally celebrated animator known for using hand-drawn animation and live action to create films that explore portrayals of life and death on screen.

Presented across two screening sessions titled ‘Matters of Life and Death‘ (11.00am Sat 29 April) and ‘The Mirror with a Memory‘ (1.15pm Sat 29 April), this is a unique opportunity to see Tupicoff’s full suite of animated films and to hear more about the key themes and processes from the filmmaker firsthand in a live In Conversation after the last screening with the director of the animation program at Griffith Film School, Dr Peter Moyes.

As part of the event, Dennis Tupicoff will be signing copies of his new book Life in Death: My Animated Films 1976–2020 in the Cinémathèque foyer at 2.30pm. His book will be available for purchase at the signing, or in advance from the QAGOMA store.

We spoke to Dennis Tupicoff about his work.

Victoria Wareham / ‘Please Don’t Bury Me’ 1976 was your first animated short, could you please talk a bit about how you first got into drawing and animation?

Dennis Tupicoff / I had no formal art training at school or university. I took and printed photographs and occasionally drew cartoons inspired by newspaper cartoonists and underground comix. In the early 1970s I shot and edited 8mm silent movies and saw a lot of films — but with no particular interest in animation. But in 1974 I heard the John Prine song Please Don’t Bury Me and could see it as animation. Now I had to learn what was required to make an animated film — and with sound.

VW / We often think of animation as the process of bringing something to life, but so many of your films take the end of life as their subject. What made you decide to focus on experiences of death?

DT / There was no decision or artistic program; things just developed that way. But I’m sure I was attracted by the irony of using animation’s ‘illusion of life’ to deal, in many different ways, with the reality of death.

VW / The skeleton is a reoccurring motif in several of your films. What made you favour the skeleton over other visual depictions of death?

DT / The skeleton is an ancient, powerful, and continuing symbol of death in many and perhaps all cultures, and can be rendered very simply in many media. By definition any skeleton is dead — without life — so any ‘life’ or movement is by definition imagined. Such skeletons can also walk and talk, and can be dressed as human beings from any place, period, class, or gender. As such they are ideal for symbolic representation in animation.

VW / The films ‘Please Don’t Bury Me’ 1976 and ‘Still Alive’ 2018 refer to specific songs and use them as their soundtracks. How did you arrive at these song choices?

DT / My use of these two songs developed in very different ways. Hearing Please Don’t Bury Me set me almost immediately on the path to making animated films. As the imagined narrative changed, and as I learned something of both animation and filmmaking, I found that I needed to change the timing of the song. So I asked a fellow student, Dave Lemon, to record a version of the song with vocals and guitar which allowed time for the various sequences, including one in total silence.

For many years I’d been a fan of the Melbourne band The Slaughtermen and particularly their rock/gospel ‘live’ version of God’s Not Dead. Eventually I had an idea which I thought suited the song and which — though edited for integration into the film’s action — required no re-recording of the 1985 original. That was Still Alive 2018.

VW / A few of your animations draw from your childhood experiences living in Darra, Brisbane. Did you always intend for your work to have an autobiographical reading?

DT / The autobiographical films all come from either memories or the scant ‘visible evidence’ of my childhood in Darra: stories about dogs, a child’s thoughts about death and nothingness, memories and non-memories about going to the ‘pictures’ before television. But each film was triggered by an experience as an adult in the present: a young daughter asking for a dog, the death of a parent, seeing an old photograph from a period before memory: me as a toddler.

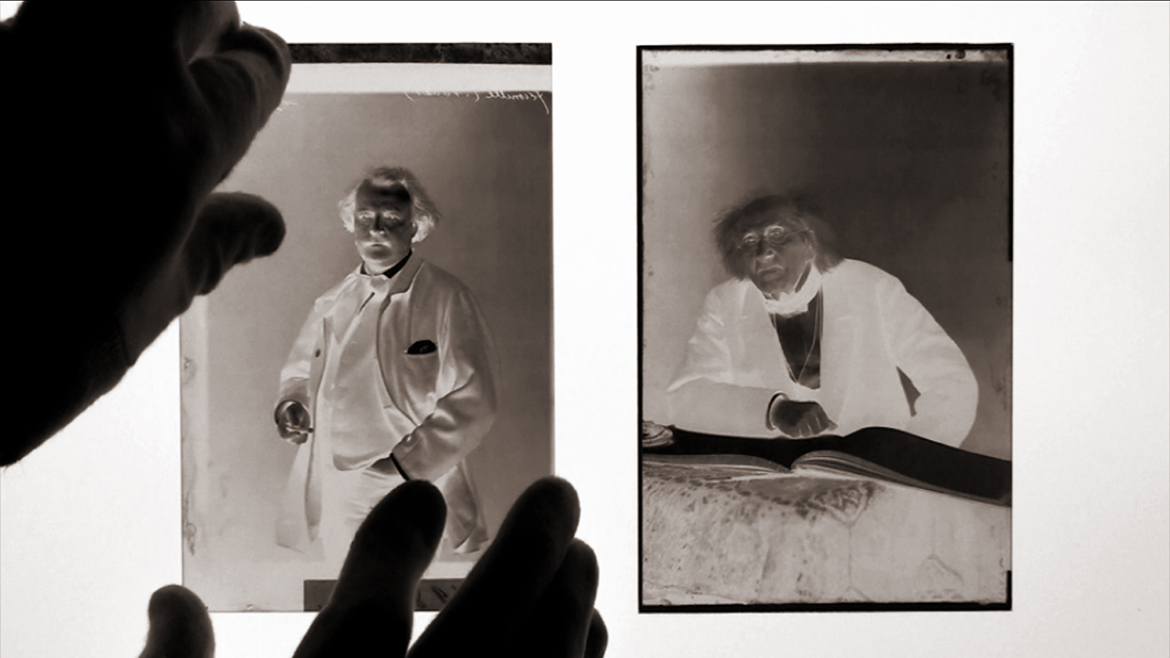

VW / Photography comes up in a number of your films, particularly ‘A Photo of Me’ 2017 and your most recent animation ‘The Only Photograph of Emily Dickinson, American Poet’ 2023. What is the significance of photography to you and your films?

DT / Photography has been described as ‘the mirror with a memory’, and each photograph as one ‘decisive moment’ preserved by the photographer as a proof of life from the vast flow of space and time. Animation, on the other hand, has never lived. Photography and cinematography capture the image of reality in all its infinite detail; everything else is thought and imagined, and can be animated.

VW / Animation, and in particular, your use of rotoscoping, appears to be a stand in for the moments where photography or documentary fails, in that it can represent the imagined or remembered moment. What first drew you to using rotoscoping in this way?

DT / Despite security cameras and mobile phones, very little of our reality is captured photographically. Everything else has to be remembered or imagined and re-staged as either live-action or — eventually, and with its infinite possibilities — as animation. The rotoscope technique uses cinematography’s images and its uncanny ‘trace’ of life to create a twilight form of cinema that is somewhere between reality and imagination, life and death. With my first autobiographical film, The Darra Dogs 1993, I resisted the use of rotoscope. Defying the risk of awkwardness in the animation — I had never animated a four-legged animal — I decided that these memories should be hand-made from their source in memory, without the aid of direct live action reference material.

VW / For independent animators, it can often be challenging to secure funding to get a project off the ground. Have you ever received funding for your films?

DT / All the films from Please Don’t Bury Me 1976 (with a cash budget of $530) to Chainsaw 2007 and The First Interview 2011 received funding from State and/or Federal government sources, and sometimes from the ABC or SBS as well. This all petered out during the early 2010s. Since then, experienced independent film makers have made their short films largely without any financial support, apart from the possibility of crowd funding. This has seen both the ambitions and the number of films shrink dramatically. To remain active, independent animators must now devote considerable funds and vast amounts of time to making shorts. And then there is the (also expensive) process of entering festivals where the films may — or may not — be seen.

VW / Is there a new project that you’re currently working on?

DT / I’m working on several ideas for short films. Their production will be subject to available time and funds — as is the highly-developed live action/animation feature film, with script and animation storyboard, that awaits production.

Victoria Wareham is Assistant Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

The Australian Cinémathèque

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) is the only Australian art gallery with purpose-built facilities dedicated to film and the moving image. The Australian Cinémathèque at GOMA provides an ongoing program of film and video that you’re unlikely to see elsewhere, offering a rich and diverse experience of the moving image, showcasing the work of influential filmmakers and international cinema, rare 35mm prints, recent restorations and silent films with live musical accompaniment by local musicians or on the Gallery’s Wurlitzer organ originally installed in Brisbane’s Regent Theatre in November 1929.

Featured image details (left to right): Production still from Please Don’t Bury Me 1976 / Production still from Chainsaw 2007 / Production still from The Only Photograph of Emily Dickinson, American Poet 2023 / Director: Dennis Tupicoff / Images courtesy: Dennis Tupicoff

#QAGOMA