Our understanding of Australia has been shaped by the medium of photography, its development in the 1840s parallels the growth of the colonies and settler relations with Indigenous Australians. Nineteenth-century photography was largely about recording what was encountered — the people and the landscape — as seen in the Queensland photographs of Richard Daintree (illustrated).

Richard Daintree ‘Free selector’s slab hut’

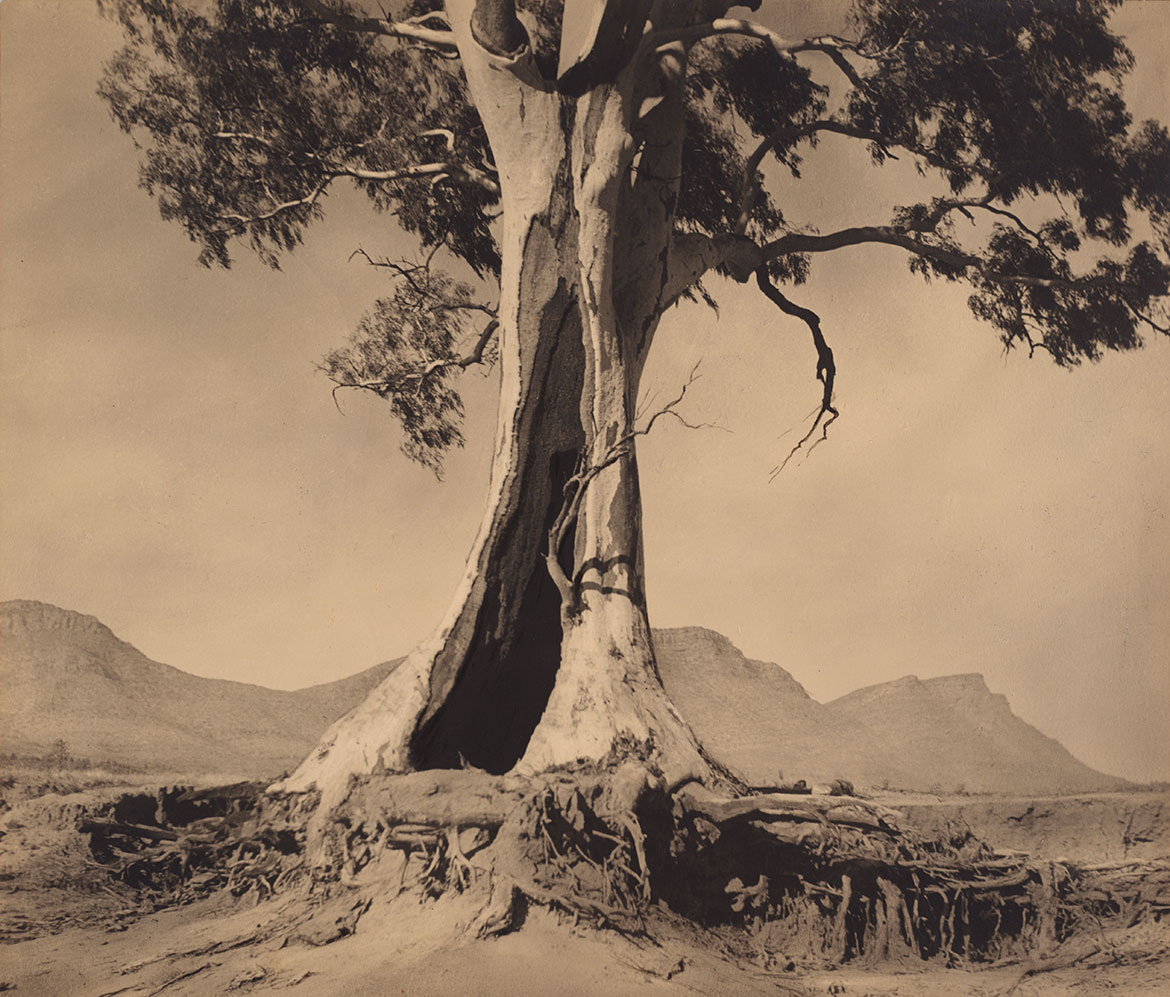

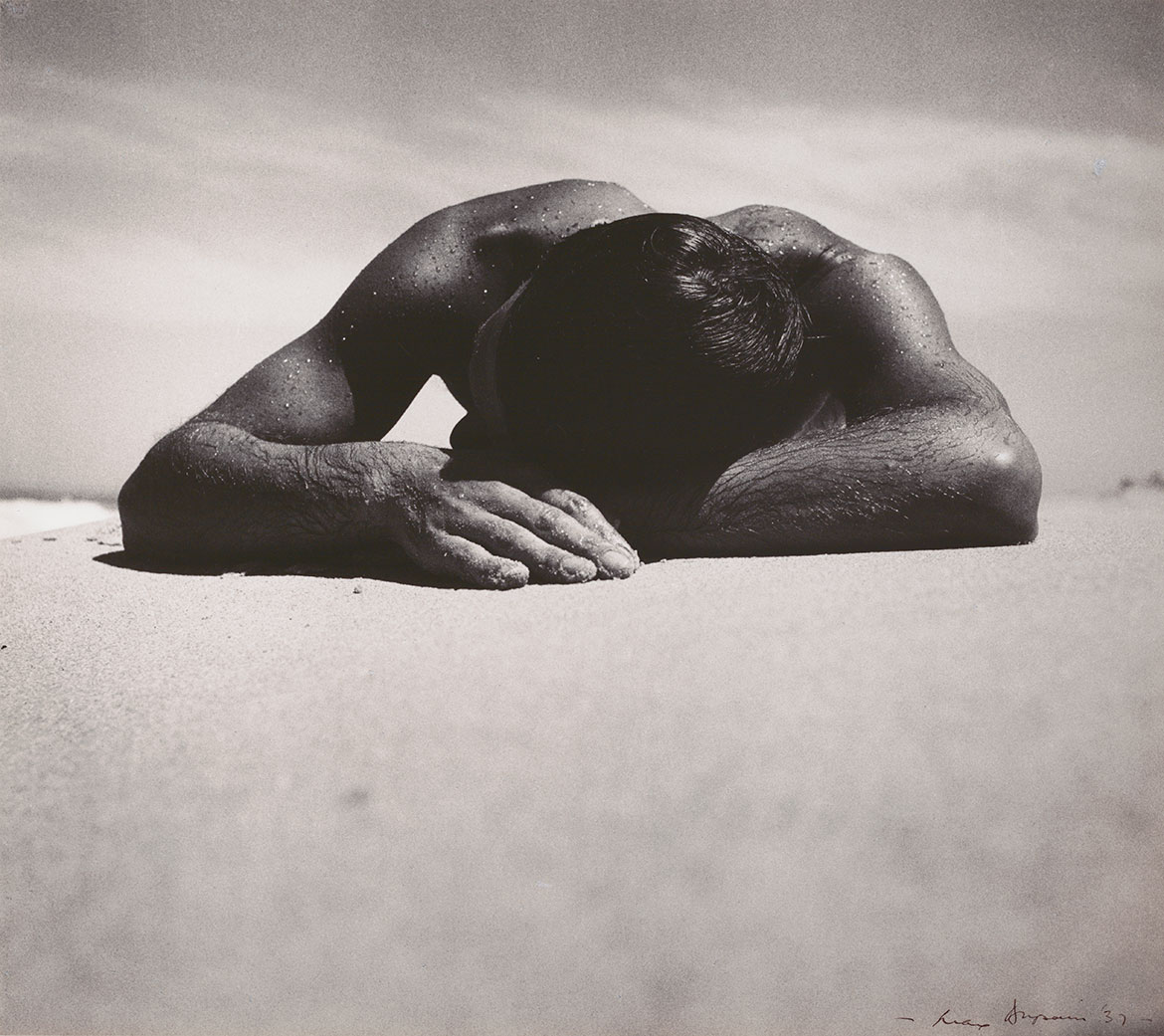

The early twentieth century witnessed greater artistic interpretation of the medium. Harold Cazneaux (illustrated) was one of the talented photographers who rose out of this movement, developing a unique style that foreshadowed the next wave of photographers, such as Max Dupain (illustrated) with his depiction of a rapidly changing Australia.

This change was at its most confrontational point during the protest movements of the 1960s and 70s, with the emergence of the youth-orientated counterculture, the women’s movement and indigenous land rights. This period encouraged a new type of photographer, one who used the medium as a means of personal and artistic expression as well as a potent tool for recording relationships, and the concept of our time and place in the world. A powerful example of this is the diaristic and durational photography of Sue Ford.

Photography as a practice underwent scholarly and curatorial re-evaluation in the 1970s and began to be collected seriously by public galleries. Through the 1980s and into the 1990s, dynamic photographic practices, often studio-based, emerged and were informed by the theoretical discourses of postmodernism and feminism, in particular, and related the history of visual art to the various traditions of photography. Diverse new works challenged the way we looked at subject and medium, and proposed new social and artistic contexts for visual expression that continue to the present day.

Harold Cazneaux ‘Spirit of endurance’

Max Dupain ‘Sunbaker’

#QAGOMA