We highlight five women artists who reflect on the cultural traditions of water, consider our reliance on water, and examine the environmental and social challenges faced by the world today.

1. Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Lorraine Connelly-Northey descends from the Waradgerie [artist’s spelling] nation but grew up downstream of the Murray River in Swan Hill, on the boundaries of Wamba Wamba and Wadi Wadi country.1 She is of Waradgerie and Irish descent and draws equally from both cultural traditions: her mother exposed her to weaving as a young girl, and her father, a farmer, passed on a talent for scavenging odds and ends. As an artist, Connelly-Northey initially set out to weave traditional fibres but soon felt uncomfortable taking plants from Swan Hill, as her own country lay further north.2 Instead, she began to prospect nearby farmland and rubbish dumps for scrap metal, reusing discarded materials as her father had taught her.

Connelly-Northey creates organic forms with hostile materials; her narrbongs are fragile yet sharp to the touch. It is in the combination of these two elements that her work finds resonance. Custodianship of country and European agriculture reside in these objects; traditions lived and passed on for generations, as well the debris of settler infrastructure. At a time when the water resources of the Murray-Darling Basin are so contested, and we must balance the needs of farming and the environment, her work suggests a coming together of two different connections to the land.

Sophie Rose is Assistant Curator, International Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 The artist choses to spell ‘Waradgerie’ as her maternal grandfather did, rather than the more commonly used spelling, ‘Wiradjuri’.

2 Diane Moon, ‘Lorraine Connelly-Northey: Mistress of iron’, in The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2011, p.103.

2. Yayoi Kusama

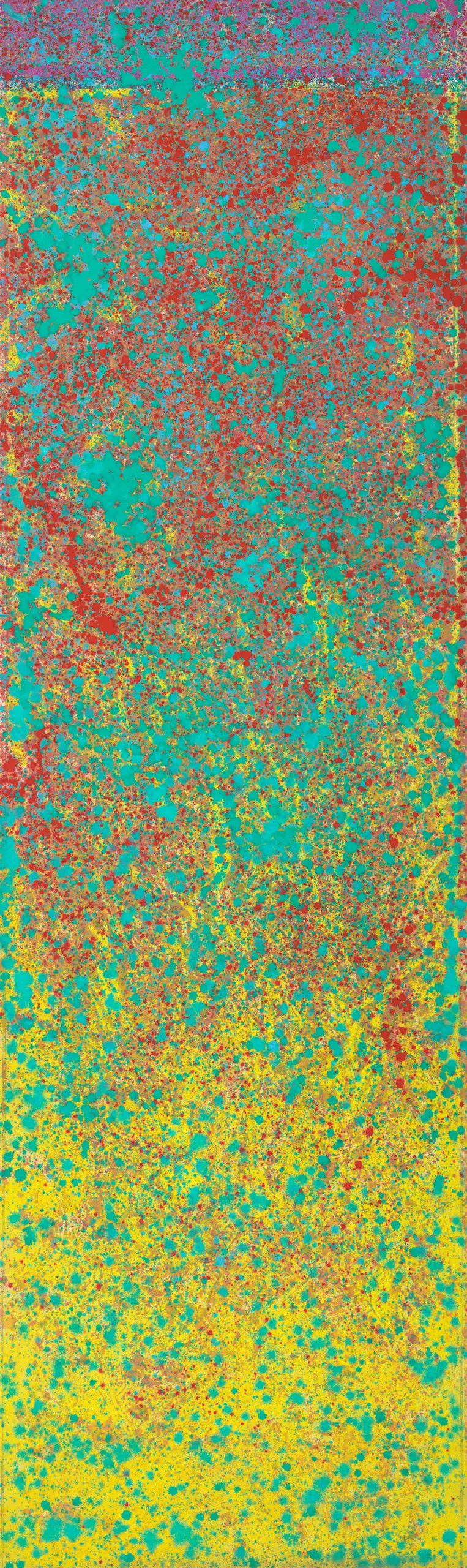

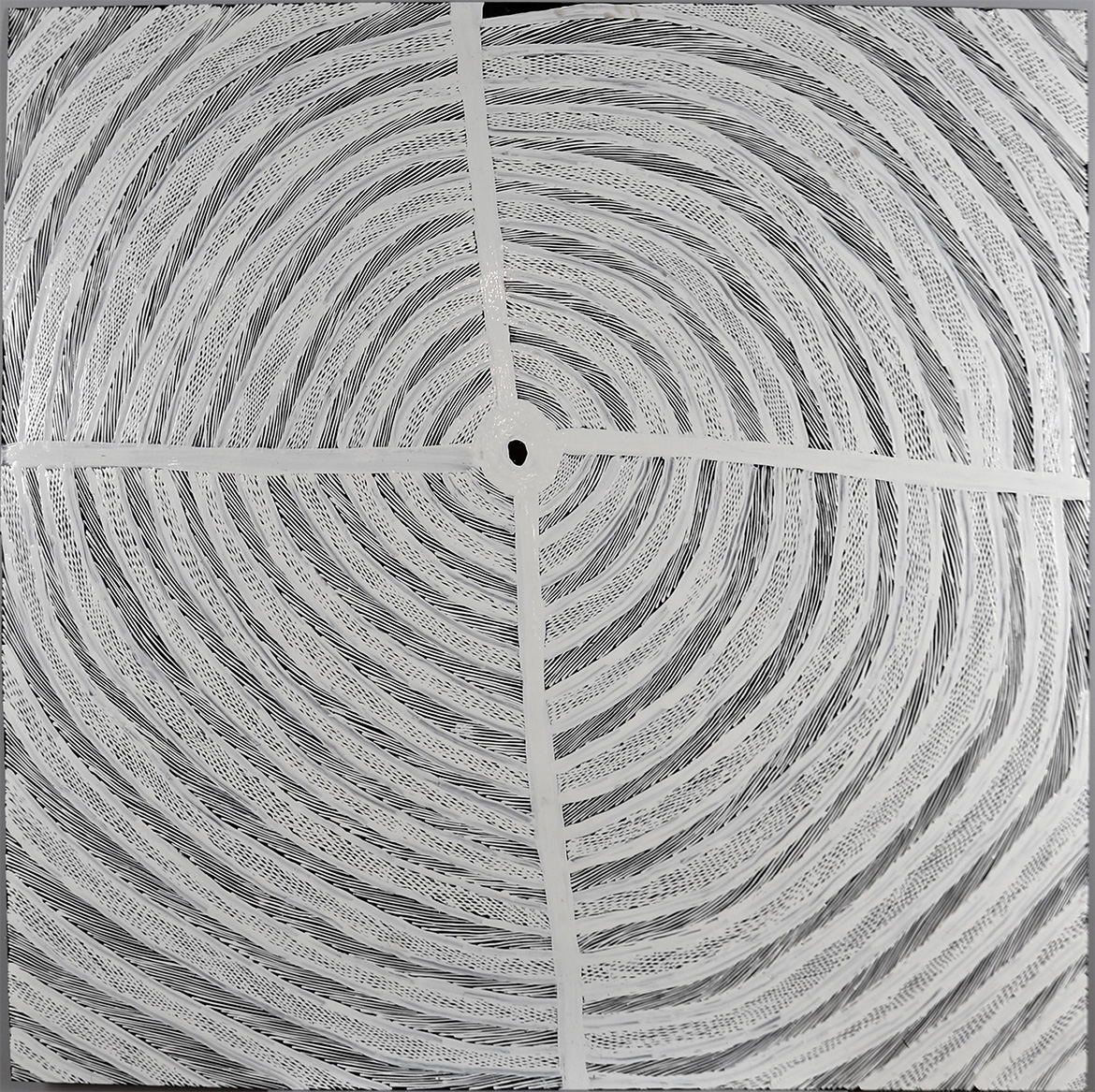

The Infinity nets are among the most celebrated of Yayoi Kusama’s many artistic innovations, and have remained a consistent feature of this pioneering Japanese artist’s practice for 60 years. Kusama first unveiled these paintings in New York in 1959 — at a time when some artists were seeking new directions away from the powerful legacy of American Abstract Expressionism — and today they can be seen as anticipating later developments in Pop, Minimalism and Concrete Art.

The early net paintings were watercolours that bore the title Pacific Ocean, which Kusama produced in an attempt to replicate the ‘shallow space’ created by the waves she observed when flying from Tokyo to Seattle in 1957. In these works, one colour was painted in tight repetitive loops to form undulating nets over a monochromatic ground. On relocating to New York in 1958, Kusama began executing the paintings in oil, and they grew in scale, often covering entire walls, anticipating her later and equally innovative installations. Lacking a discernible centre and disregarding conventions of composition or perspective, these works proposed painting not as the production of modular, autonomous entities, but as objects within the world, or surface driven three-dimensional forms.

With its highly practised, confident loops, restrained palette and use of acrylic paint to enable quick execution, Infinity nets 2000 is typical of Kusuma’s work made at the end of the 1990s, when she was belatedly embraced by the international art world. Unlike the aggressive mark making of Abstract Expressionism or the erasure of gesture characterising Minimalism, this work bears the trace of an immense labour consisting of accumulated tiny gestures. The optical effect of its undulating fields owes more to the material qualities of the painted surface than to any illusions of pictorial depth. It is this perfection of affect, as opposed to direct representation, that preserves the work’s origins in the peaks and troughs of oceanic waves.

Reuben Keehan is Curator, Contemporary Asian Art. QAGOMA

3. Dhuwarrwarr Marika

In Milngurr 2018, Dhuwarrwarr Marika depicts the heart of the most important theme for her Dhuwa moiety Marika family, the journey of the Djang’kawu creator ancestors who followed Banumbirr (the morning star) from Burralku (an island of ancestral dead), rowing their canoes across the sea using mawalan (digging sticks) as paddles. They carried woven mats and conical baskets with them, transformed when they reached land into sacred objects through ritual singing and dancing. On arrival at Yalangbara they pierced the earth with their digging sticks to make Milngurr, the first of a series of sacred freshwater springs. After giving birth there to all the Dhuwa moiety clans, the sisters continued across eastern Arnhem Land to create their clan estates, language, sacred law and ceremony.

Dhuwarrwarr Marika has painted Milngurr on the surface of an aluminium panel left over from an architectural commission at Dhawurr, the new boarding facility attached to the local Nhulunbuy High School.1 Although she is using this unlikely material for the first time, in handling the oil based enamel, Marika has created an attractive glossy surface that shimmers against a black background; the fluid consistency of the paint forming an embossed texture.

Diane Moon is Curator, Indigenous Fibre Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 Gunybi Ganambar initiated an eastern Arnhem Land movement using a range of discarded material recycled into works of art, first featured in the exhibition ‘Found’ at Annandale Galleries, Sydney, in 2013.

4. Vera Möller

Vera Möller is captivated by the endless variety of nature. She looks closely at underwater and intertidal life, as well as fungi, moss and microorganisms invisible to the naked eye. She first trained in biology, studying the freshwater ecology of Bavaria in her native Germany before making the wide and varied landscapes of Australia her home.

Möller describes her installation vestibulia 2019 as a kind of fiction, a composite of observed and invented parts. Like an underwater garden, the work evokes a coral reef complete with hard and soft corals, seaweed, nudibranchs and a wealth of other life. Each small sculpture reaches up as if drawing sustenance from the water column, and together offer a wonderful array of patterns and colours. Möller also leaves the white clay of many of these elegant forms unadorned, evoking the skeletal remains of coral and recent damage to the Great Barrier Reef. vestibulia not only celebrates the wonder of such sites but also reminds us of their vulnerability as water temperature and ocean acidity rises. In Möller’s works, curiosity and wonder fuel imagination, creativity and care.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow is Curatorial Manager, International Art, QAGOMA

5. Judy Watson

Judy Watson’s painting string over water (walkurrji kingkarri wanami) 2019 immerses us in veils of cobalt and indigo blue, as if we were underwater, looking up to the dappled light and warm air above. Shafts of sunlight seem to lead us upwards from the cool blue depths. Watson speaks of her work as encompassing both saltwater and freshwater sites she has returned to throughout her life: places on the east coast, and inland, south of the Gulf of Carpentaria, in far north-western Queensland. Here her mother’s people, the Waanyi, acknowledge Boodjamulla, the Rainbow Serpent, as responsible for the life-giving waters, dramatic gorges and waterways:

No waterholes or permanent water are believed to have existed in the area before the coming of Boodjamulla. He created Lawn Hill’s deep gorge holes and now keeps them full of water to keep his body wet; if he ever leaves, the waterholes will dry up.1

Watson evokes the generative energy of Boodjamulla, celebrated in rock paintings throughout the region, in long spiralling fibres of string. The string seems to float over the watery depths and is delineated in black, as if seen from beneath in shadow. One fibre joins another; fragile threads are made stronger when entwined. Women are traditionally the string-makers. Fibres are rolled up and down the leg to bind them together, the small hairs being picked up and becoming a part of the string. Although this string may appear humble in form, it has deep symbolism and is a precious material and metaphorical link to family and ancestry, evocative of the spiralling double helix form of DNA.

Considering the future as well as the past, the global as well as the local, Watson overlays parts of the painting with intricate dappled whorls of white, drawing from her observation of the patterns formed as water drips through melting snow. For her, this age-old seasonal thaw has new meaning as we consider the impact of climate change upon the sustaining rhythms of our known ecology, rhythms linking past generations and the generations to come. Watson says:

Water is a conduit for my creativity, I think through water, swimming, washing, showering, pouring and pooling washes of liquid paint onto my canvases and paper. Water is refreshing, cleansing, an important life source, the hidden jewel that feeds the country. When I am immersed in water, I feel connected and alive.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow is Curatorial Manager, International Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 Arthur Petersen, as relayed to Grahame Walsh and quoted by Paul SC Tacon, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol. 18, no. 2, 2008, p.167.

Featured image detail: Lorraine Connelly-Northey Narrbong (String bag) 2007

#QAGOMA