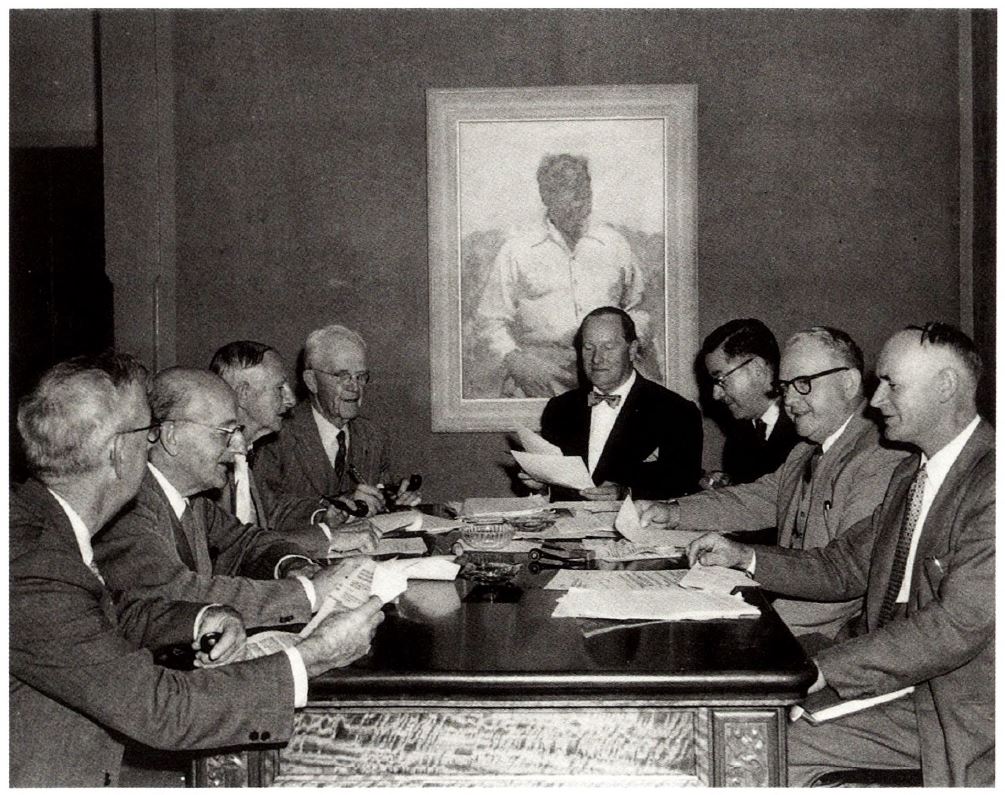

In 1942 a visit by Daphne Mayo (1895-1982) to William Dobell’s Kings Cross studio in Sydney resulted in the acquisition of The Cypriot 1940 (illustrated) for the Queensland National Art Gallery’s Collection (now QAGOMA). Just two years after its completion Mayo had purchased Dobell’s largest and most ambitious work — the subject of many preliminary studies over several years in London and the ‘tour de force’ that Dobell had been determined to paint upon his return to Australia.

RELATED: The life and art of William Dobell

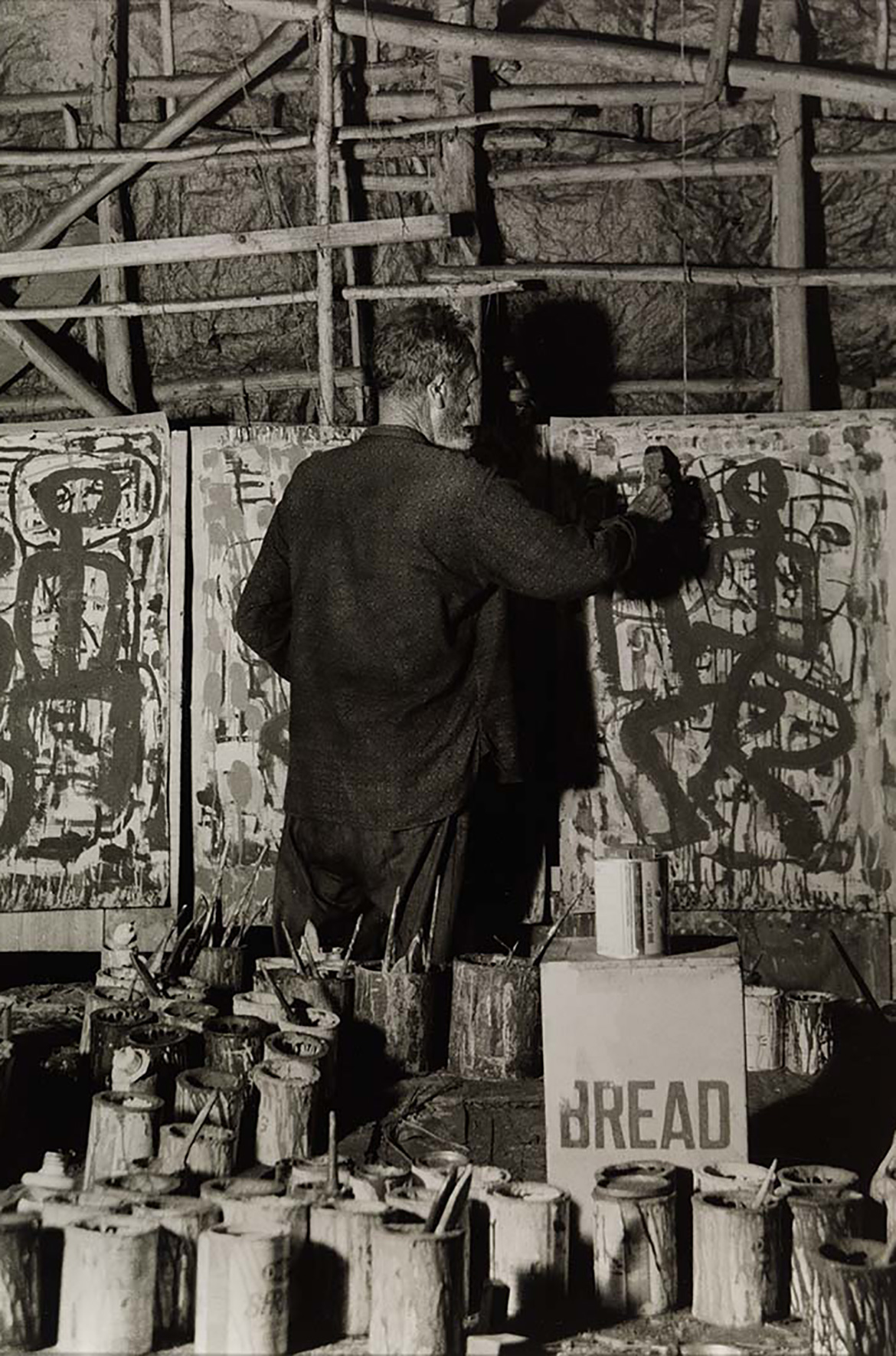

Dobell (1899-1970) was in Europe for ten years, initially on a Society of Artists Travelling Scholarship. Learning his trade, experiencing the works of the great painters and slowly developing his own style, he would come back to Sydney with an expansive armory of skills and experiences. Most of his works in London were small-scale; many were sketches and studies that he intended to develop into finished oil paintings upon his return.

The London experience was financially lean for Dobell but it allowed him to live a lifestyle that suited him, to paint subjects that interested him, and to mature personally and artistically. He was less burdened with the expectations of others and could more easily experience life and advance his art. But in the end, his intention was always to bring his skills home and there to produce works that were the culmination of his development as an artist.

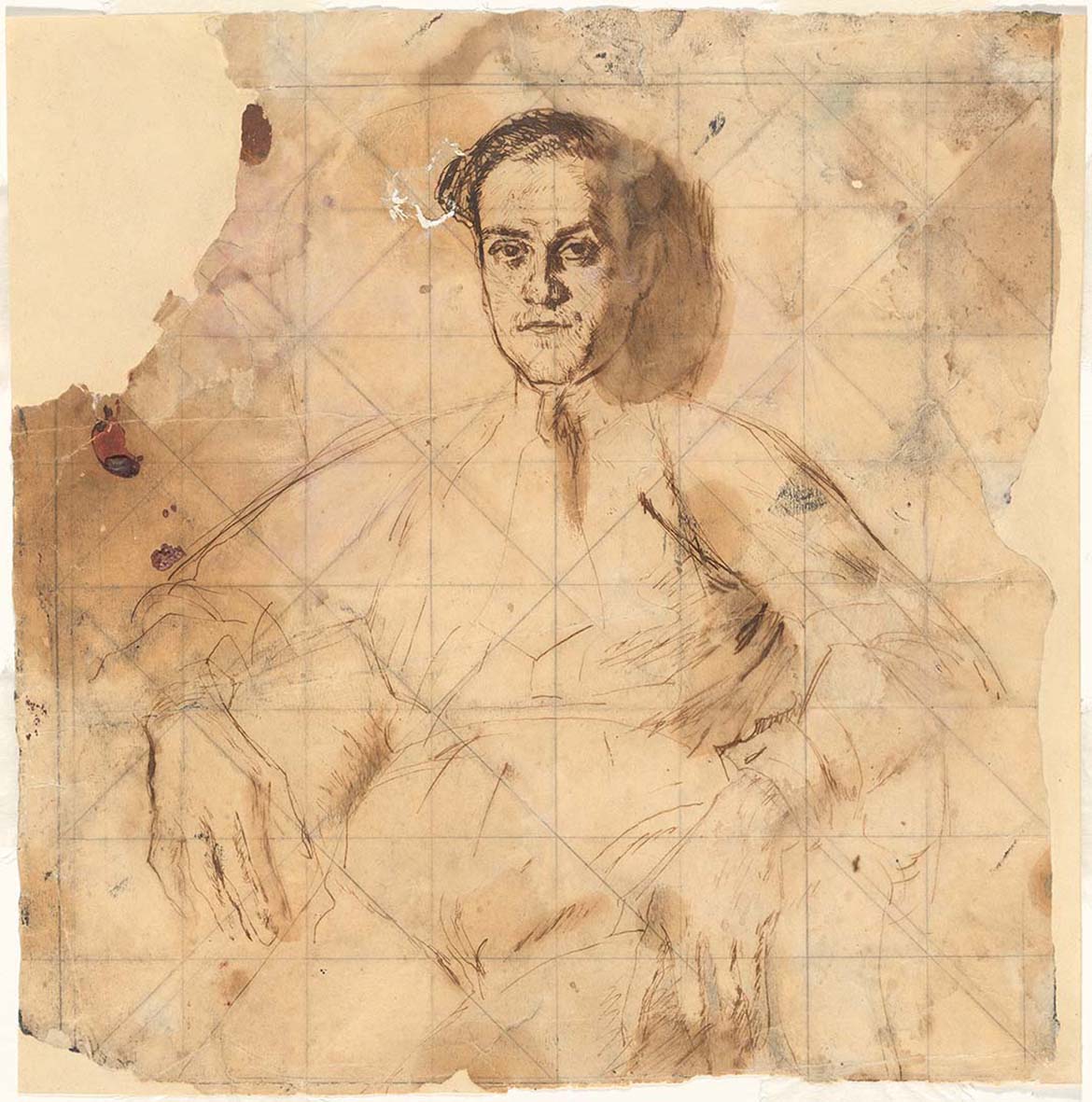

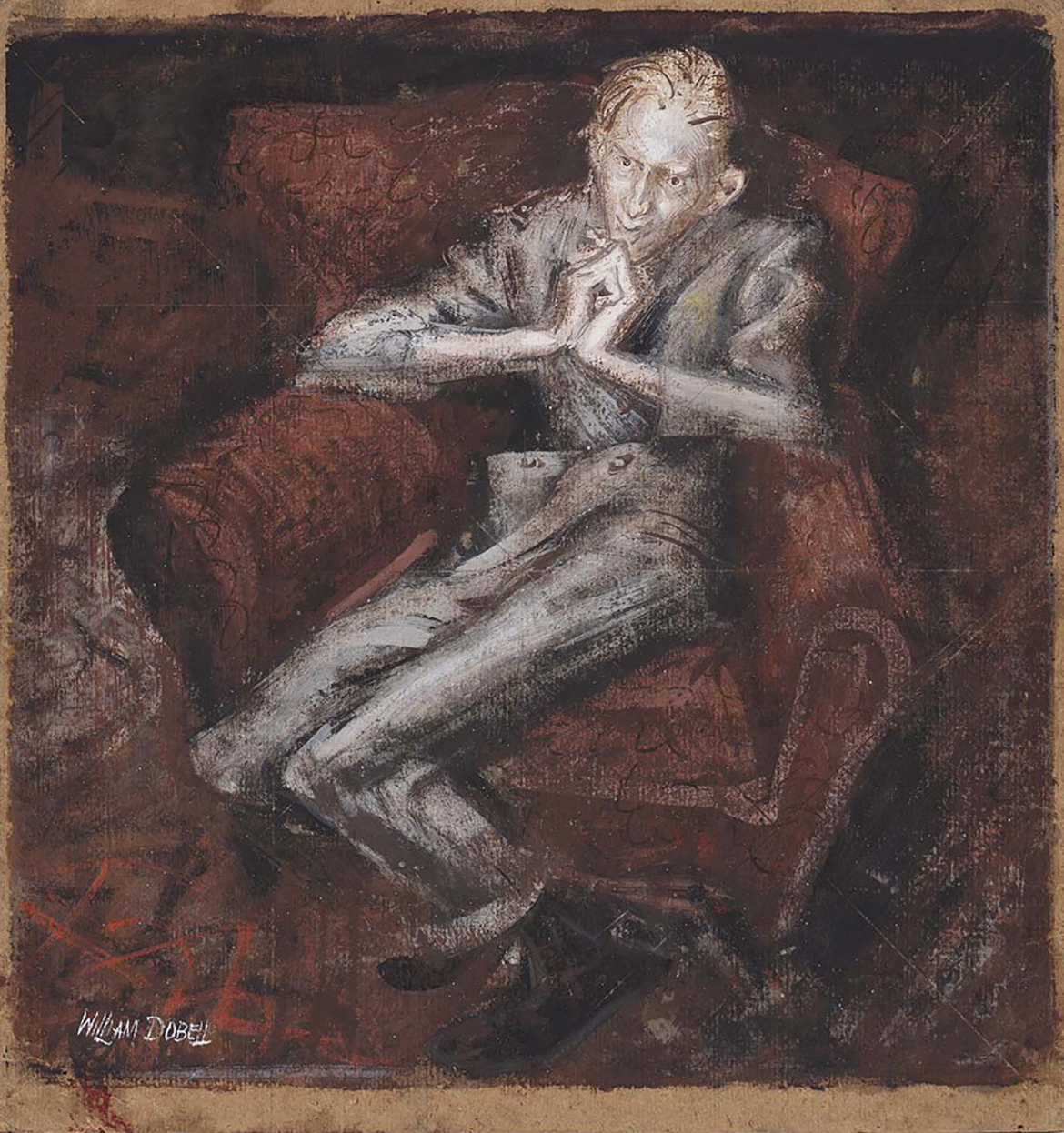

The 1930s in London saw Dobell working on preliminary studies for three major portraits: The Irish youth, Boy lounging and The Cypriot. The first studies for The Cypriot and The Irish youth appeared as early as 1934 and 1935, and Dobell’s friend Aegus Gabrielides sat many times for studies for The Cypriot during the following four years.

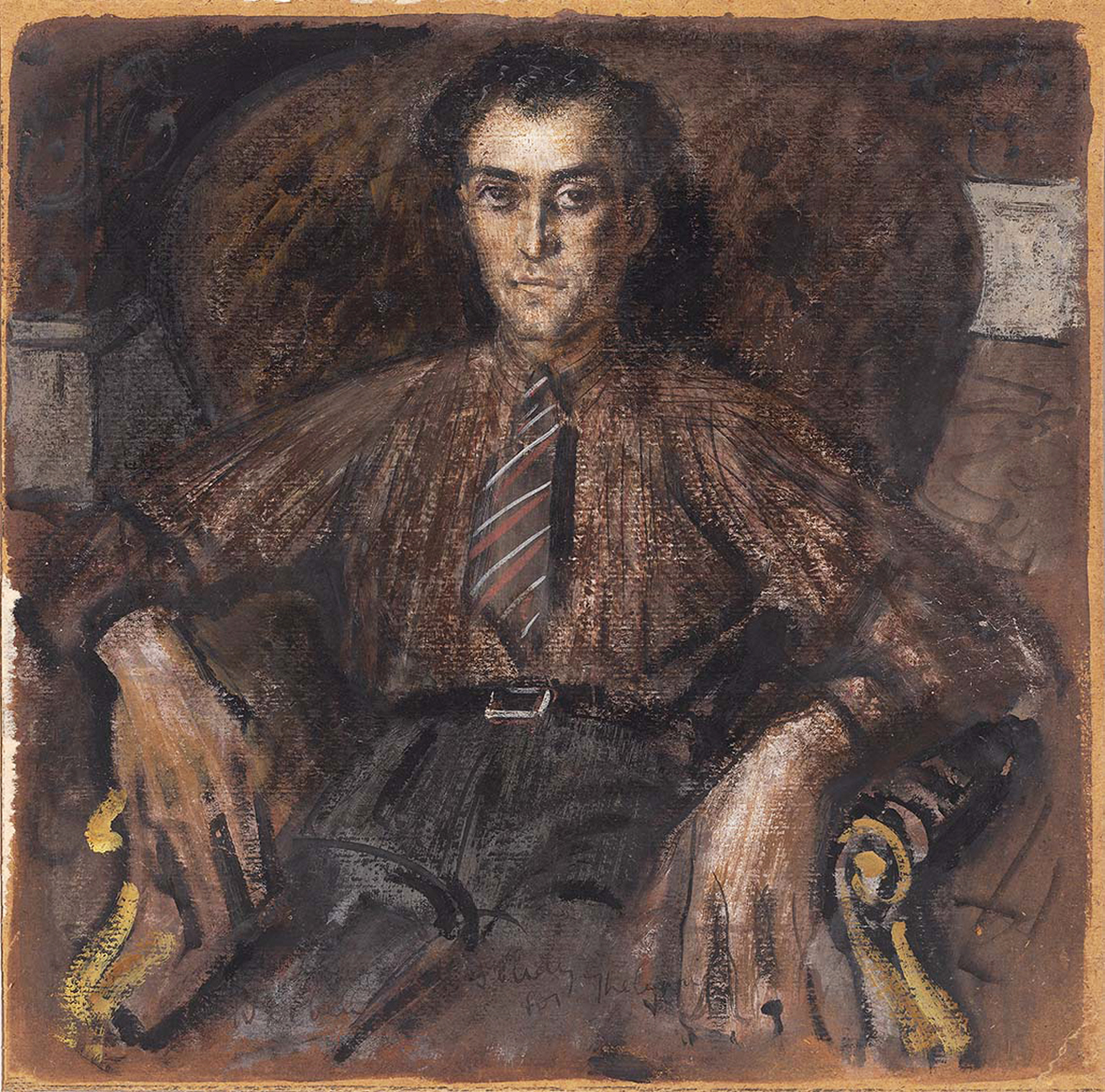

Whereas earlier studies for The Cypriot reflect Dobell’s local environment at the Slade School and Easton Road Group, those for The Irish youth show an awareness of the work of European painters such as the expressionists Chaim Soutine and Oskar Kokoschka. The completed oil painting of The Irish youth 1938 (Private collection) is the first work that defines Dobell’s own maturing style of portraiture. A quizzical, ungainly boy, viewed slightly from above, seems rather unsure of how to fill the space around him. The colour notes in red, in this instance on the signature and the boy’s tie, were to become Dobell’s trademark.

A dramatic change in The Cypriot’s evolution came in 1937 and coincided with Eric Wilsons arrival in London. Wilson had won the New South Wales Society of Artists Travelling Scholarship and he came to London full of enthusiasm and energy. Wilson was a Seventh Day Adventist whose art and religion were virtually inseparable. The two men, almost diametrically opposed in every way except for their mutual passion for art, shared Dobell’s attic in Pimlico for five months and became good friends. (Dobell gave Wilson an early study for The Cypriot.) Moreover, they seemed to spur each other to greater achievements. Dobell at this stage regarded himself as an academic painter following a long tradition; Wilson saw himself as a modernist who was on the road to incorporating Amédée Ozenfant’s brand of Cubism.

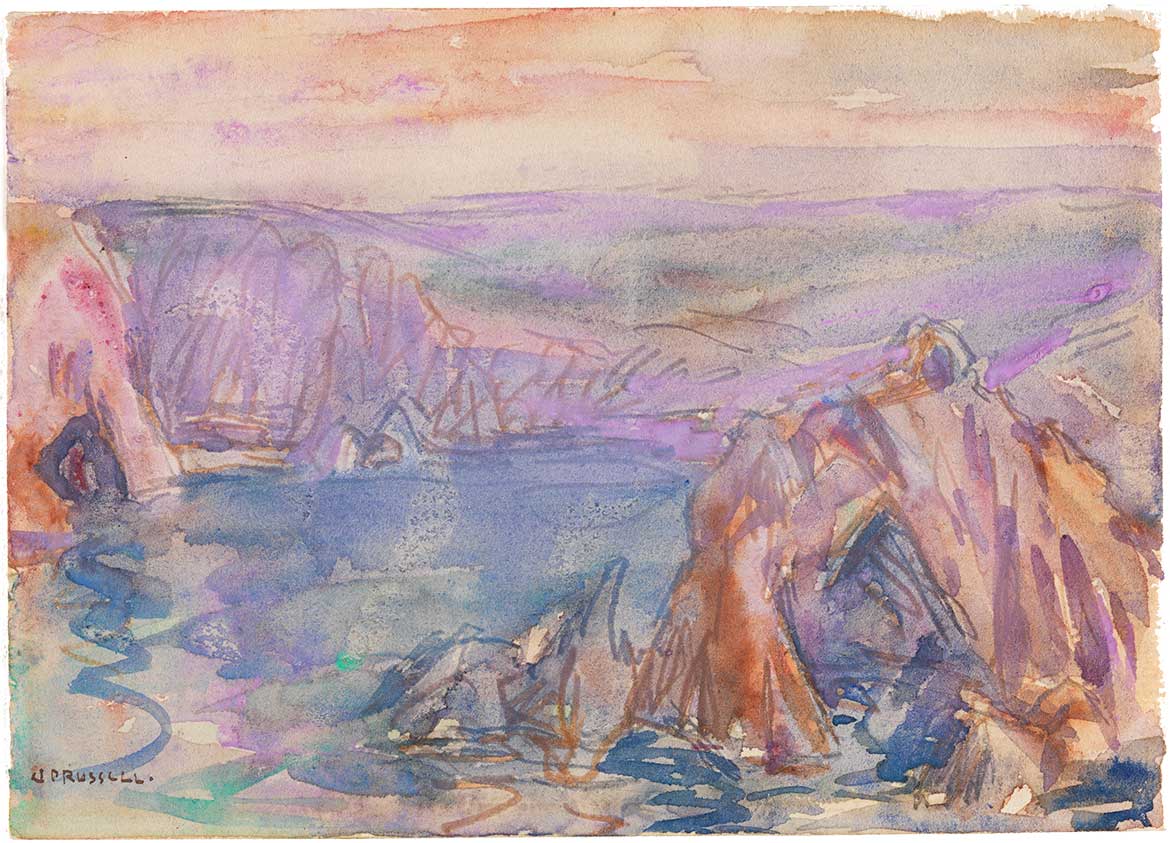

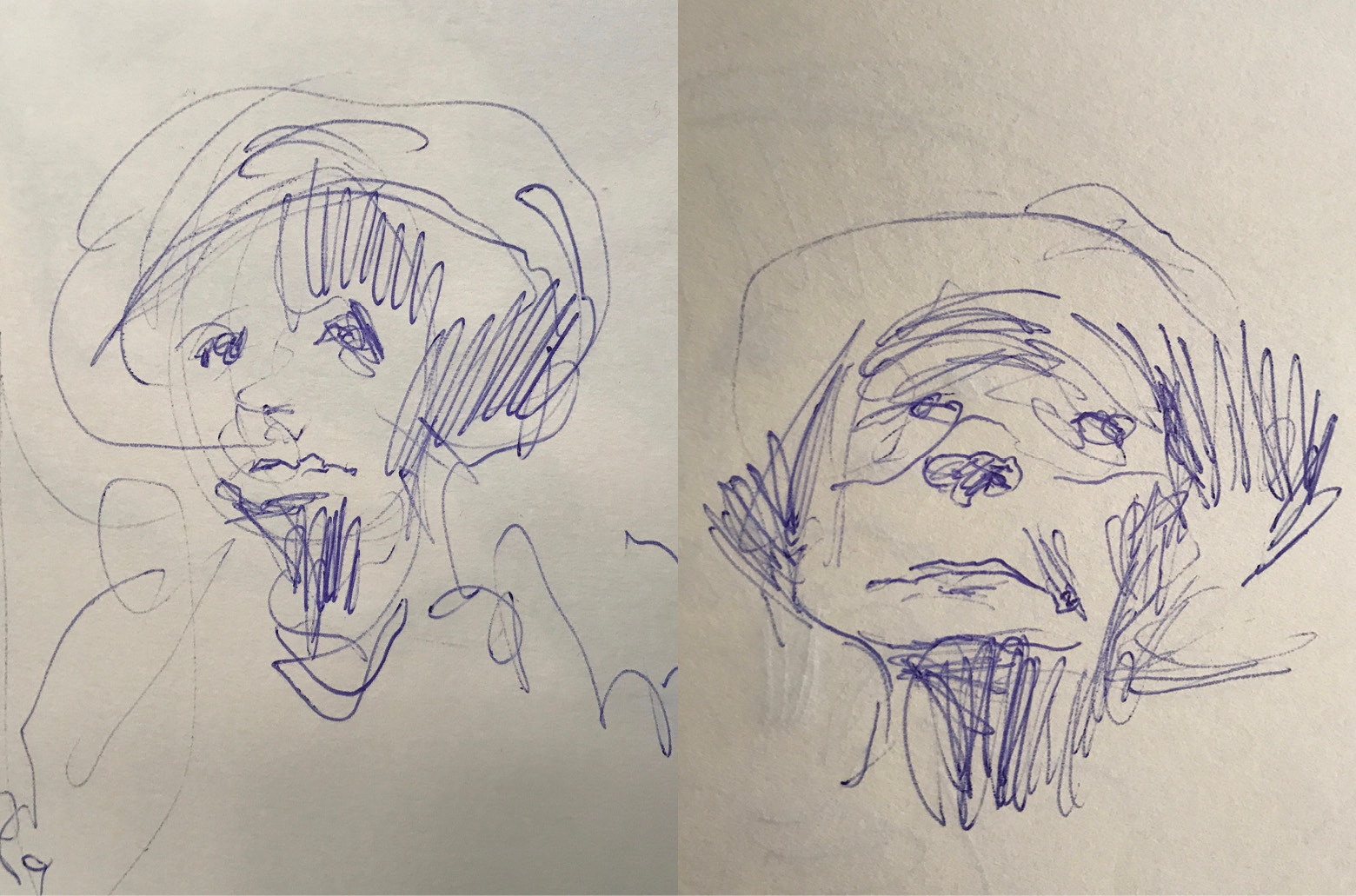

William Dobell Study for the painting ‘The Cypriot’

William Dobell Study for the painting ‘The Cypriot’

It was during this period that Dobell produced both a drawing and a painted study for The Cypriot in which the sitter takes on a formality and assurance derived from Italian Mannerist portraits. Bernard Meninsky, a teacher at the Westminster School, had advised Wilson to read Bernard Berenson’s The Italian Painters of the Renaissance. It was surely a topic of discussion between the two artists and may well have influenced Dobell’s change of approach to The Cypriot.

In December 1938 Dobell left London to return to Australia. On the way he spent some time with Wilson in Paris. They sketched together, visited a Cézanne exhibition, and Dobell rekindled the energy and resolve he needed to meet his own expectations. Upon his arrival in Sydney, the publisher Sydney Ure Smith promoted Dobell as the ‘heir to Lambert’, and the artist felt further compelled to produce his best work.

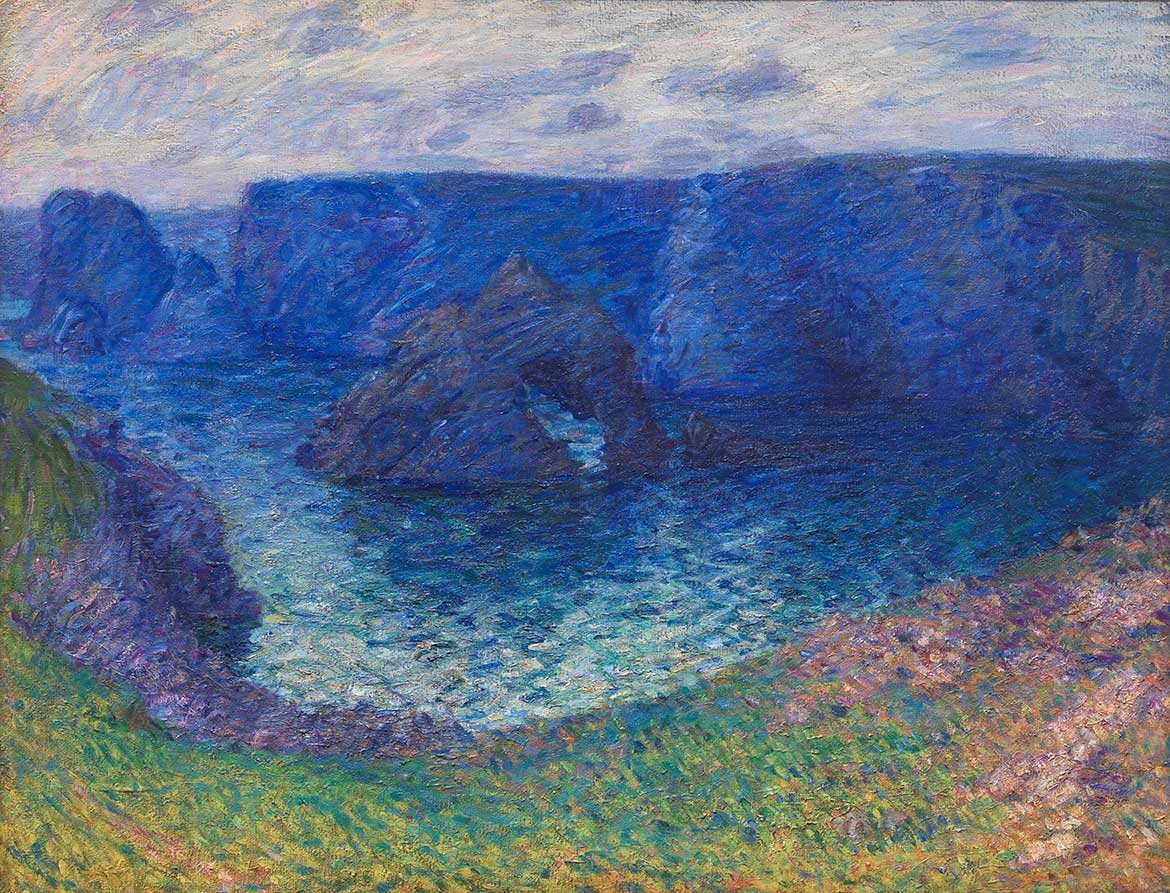

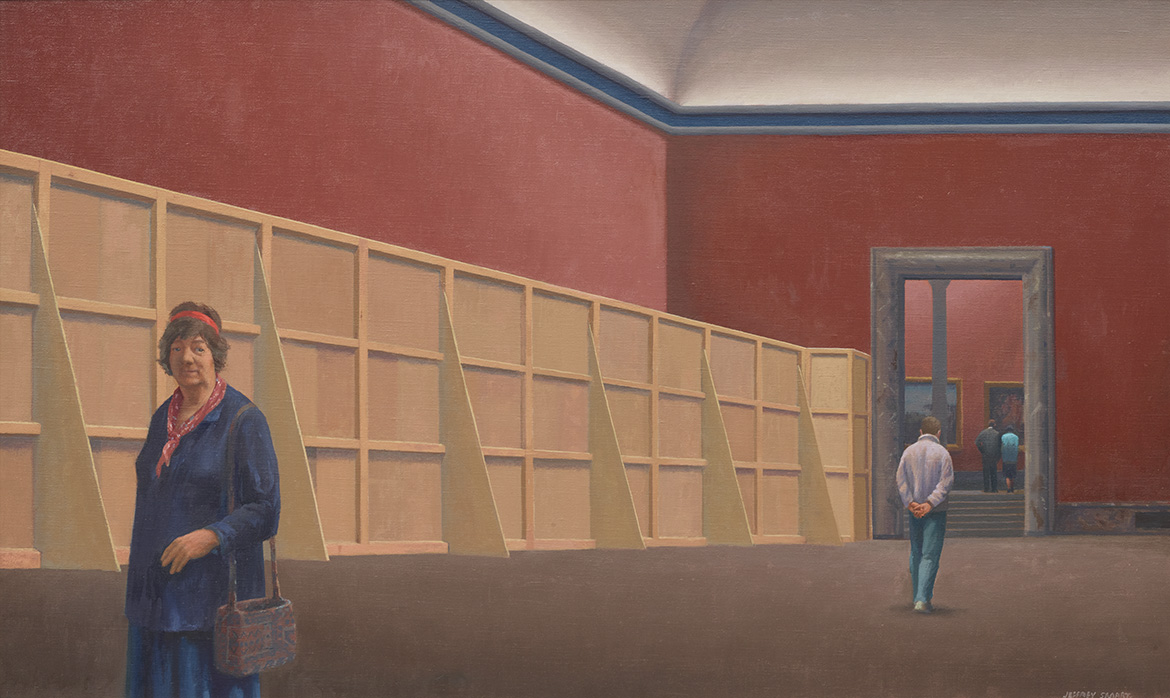

William Dobell Study for ‘Boy lounging’

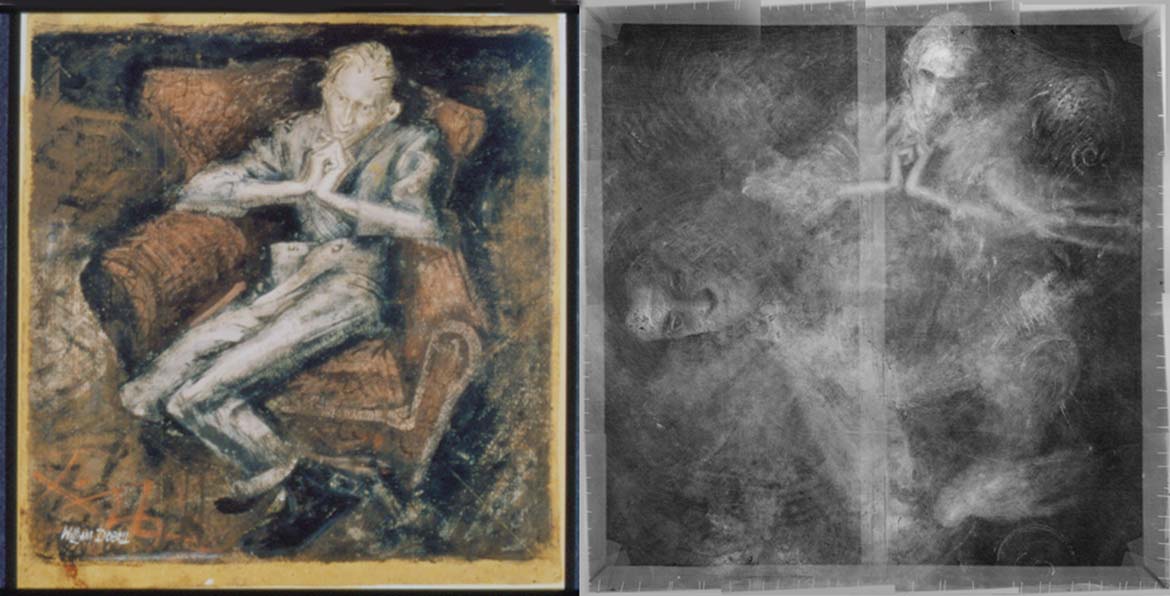

Dobell bought a large stretcher of 48 inches (121cm) square, an unusual format. He gridded up the Study for ‘Boy lounging’ 1937 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and transferred the image to this canvas. It seemed a natural progression from The Irish youth — in Boy lounging another young man slouches in an armchair, his figure elongated then crumpled into the chair. However, the transition from his small-scale London works to a large format was not straightforward and Dobell seems to have experienced some difficulties adjusting to the increased scale and pace of the work. He was still poor, working with old brushes that had dried on the journey home. The abundance of brush hairs embedded in the painting’s surface are testimony to this. Also, chemical analysis of the paint layers has shown that he was using a combination of oil-based house paints and artist’s paints, a selection mediated by economics and the large area of canvas to cover, as well as by the scarcity of artist’s oil paints owing to their requisition for use by official war artists. These aspects may have contributed to Dobell being unhappy with the finish of Boy lounging (he never went on to complete a final work). More importantly, the work was not the ‘masterpiece’ that he had aspired to produce upon his return. He decided to try again and to paint over it a new portrait of Gabrielides.

In his Kings Cross studio in 1940, Dobell set to work on The Cypriot. He completed a detailed study of the left hand using the hand of Joshua Smith as a model. As an X-ray of The Cypriot shows, he rotated the Boy lounging canvas through 90 degrees and began painting the head of Gabrielides, slightly turned, in more profile than the 1937 studies. The X-ray also reveals more tentative brushwork as he attempted to fine-tune the pose and bearing of the sitter. Unhappy with this variation, Dobell at last achieved in his mind’s eye the precise posture and attitude of The Cypriot. He abandoned the earlier working, rotated the canvas through 180 degrees and began to paint the final version of the head with great confidence.

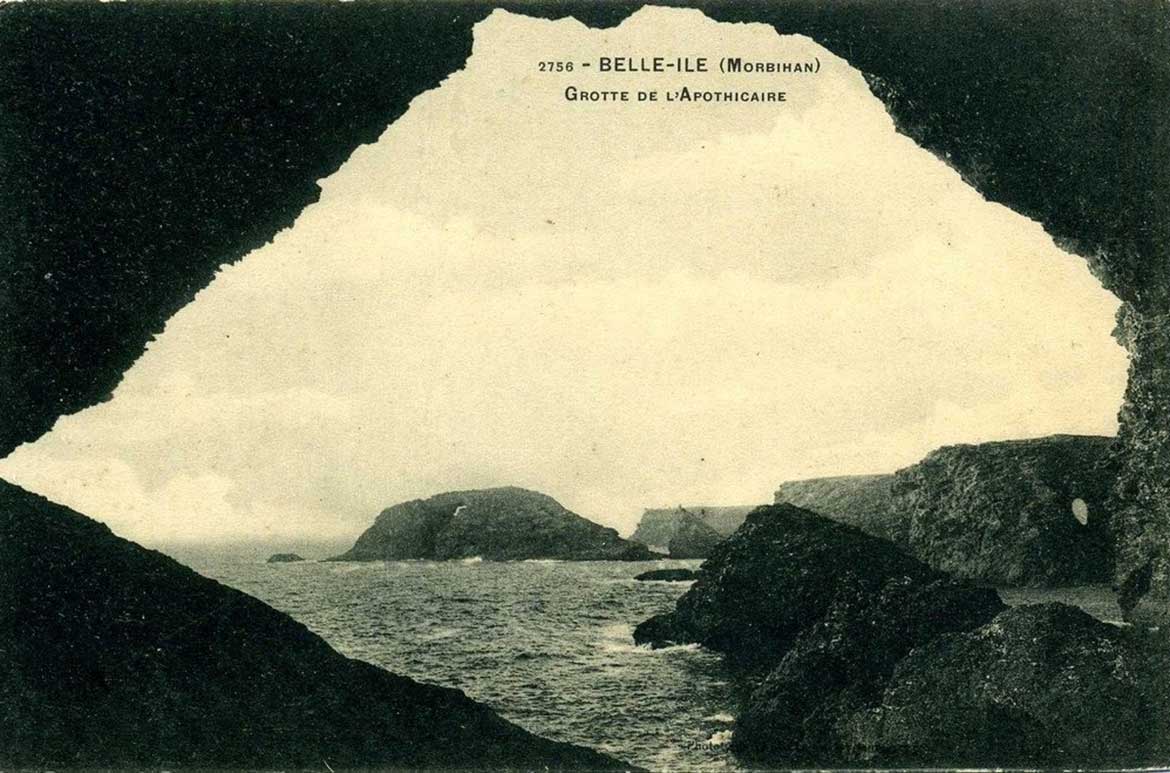

X-ray of ‘The Cypriot’

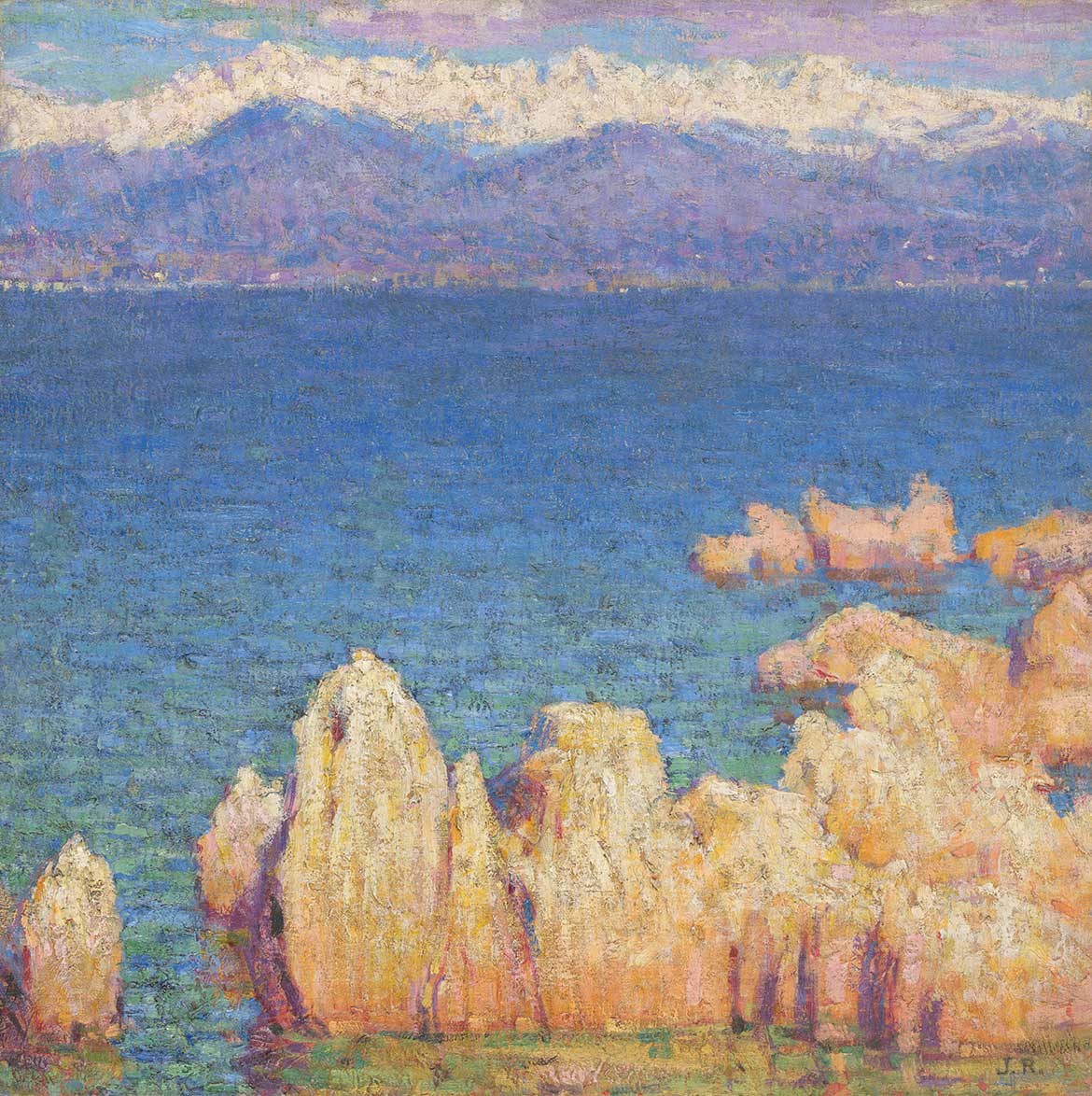

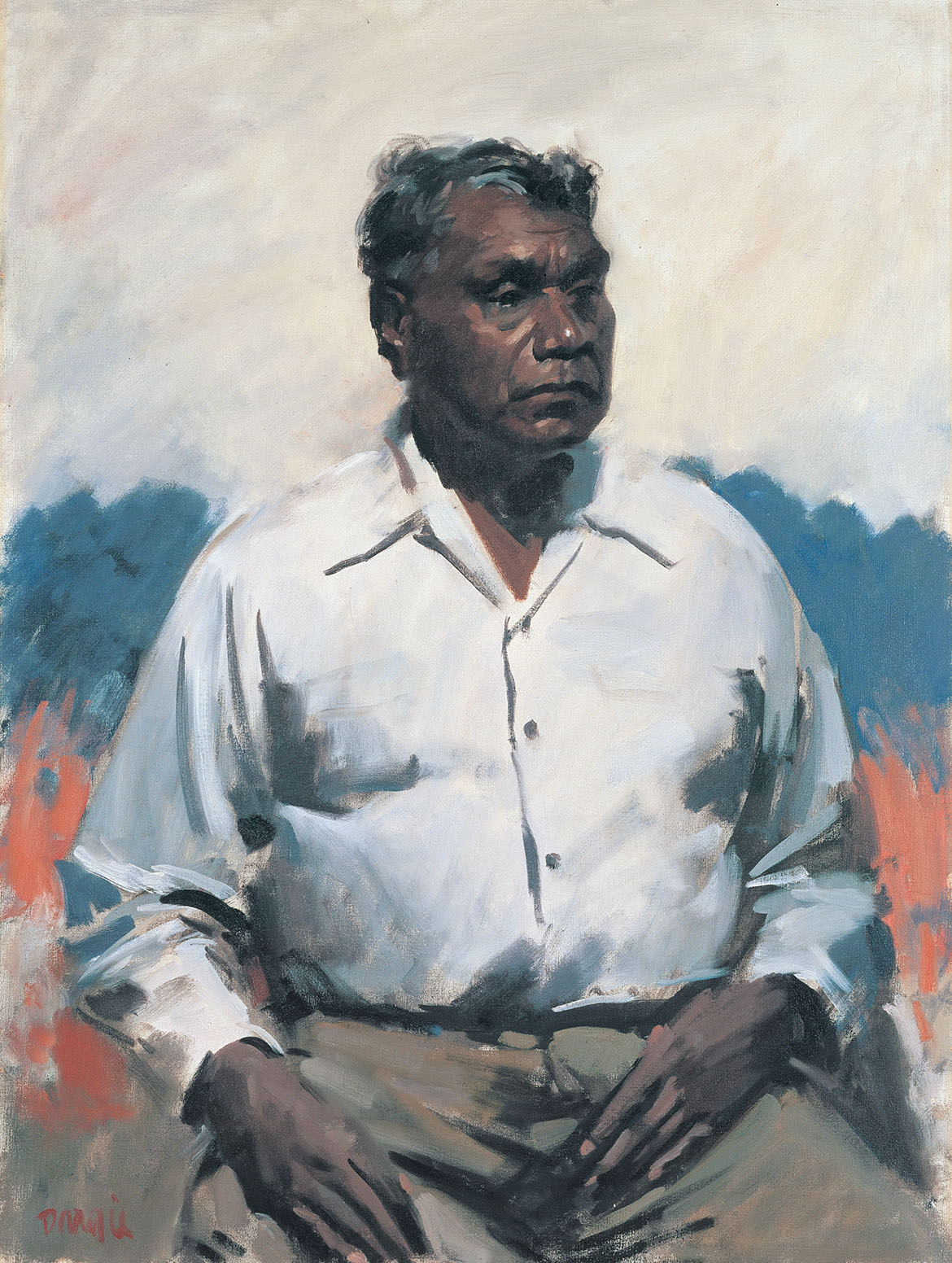

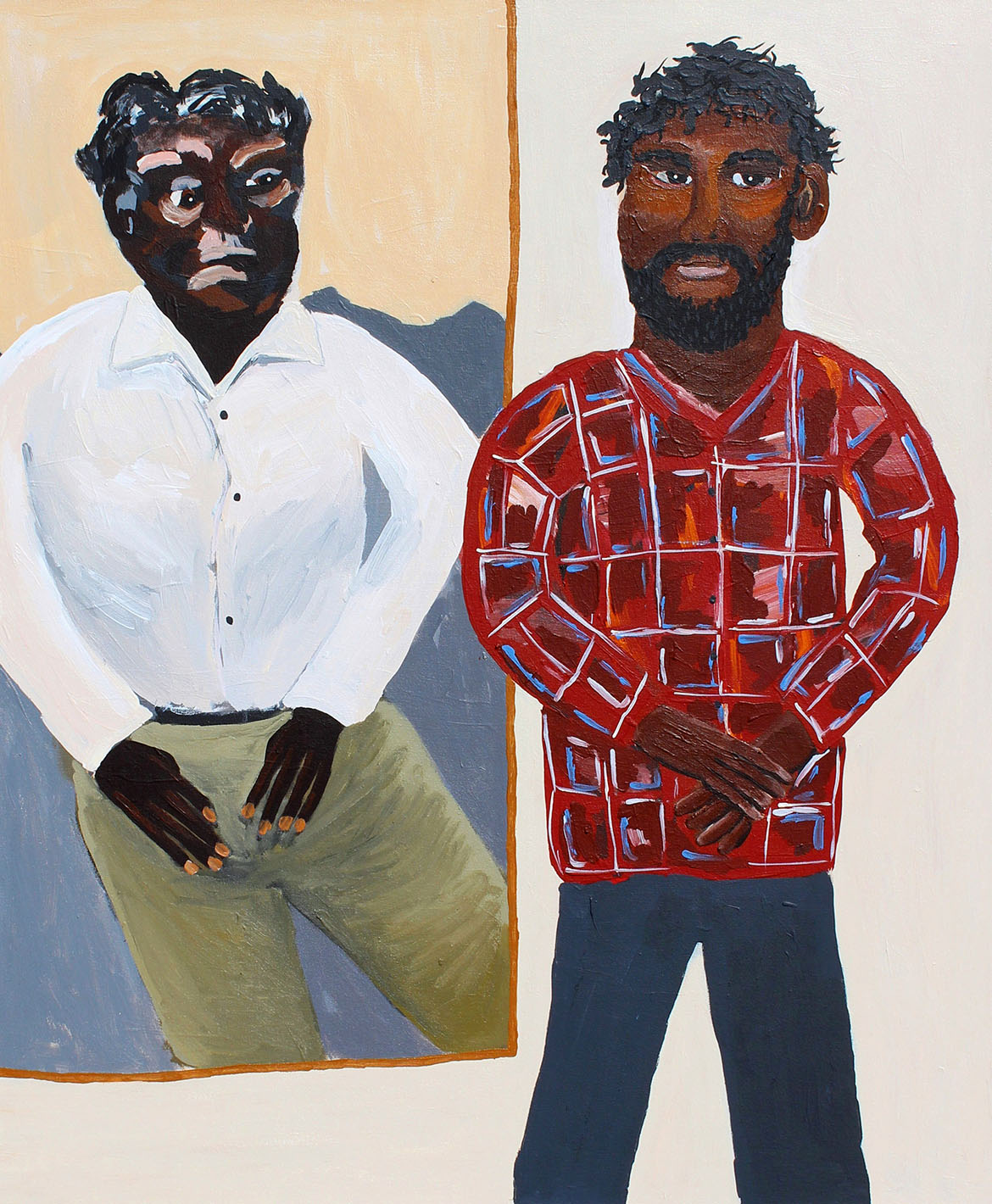

Dobell’s friend, the Greek waiter, now assumes a posture of contained energy. The torso is slightly turned; Gabrielides’s powerful left hand is closer to the viewer and arched over the spiraling end of the armchair. It is a formal, dignified pose commonly seen in the canon of Italian Mannerist portraits, such as Italian Mannerist painter Agnolo di Cosimo’s (usually known as Bronzino) depictions of nobility and clergy The Cypriot completely fills the pictorial space with a commanding presence. Gabrielides is assured and alert. His eyebrows slightly arched, he sits passively in control, regarding the viewer.

The Cypriot’s luminous face and hands, brilliant blue shirt and red tie form a radiant figure surrounded by darkness. Unnecessary background detail has been eliminated; light spilling from the top left casts the sitter’s face and hands in deep relief, suggesting a further light source from the figure itself. The cool, translucent flesh of the face and left hand is tinged with glowing sienna reflections which lend an other-worldly character to the portrait.

Both the head and hands are finely and convincingly delineated and modelled. Yet they emerge from a body which, conversely, is largely insubstantial. Substance is both emphasised and impoverished; there is no real sense of form beneath the shirt; its volume seems deflated, setting up a tension between the three forms of the hands and head of the sitter; their relationship to the torso remains ambiguous and mysterious.

William Dobell ‘The Cypriot’

The Cypriot is crafted with the full range of expressive brushwork, glazing and scumbling of the European tradition. The cushioned chair is sumptuous and richly built up with deep glazes. The handling of the cool, translucent flesh is masterly, alternating undermodelling with subtle glazes. Whether intentional or not, the predominant browns in the painting underneath (Boy lounging) act as a brown imprimatura, enhancing the old master character of The Cypriot. This imprimatura shows through in the shirt, the hair and parts of the background, adding both complexity and unity to the finish. Dobell has reinforced the effect of a brown ground with the subtle use of siennas and umbers distributed throughout the composition. The assured, hatched brushstrokes of Gabrielides’s blue stubble, the most delicate of turpsy washes on the nose and forehead, and the smudges of blue in the hair (applied with the artist’s finger) are testimony to Dobell’s great touch and bravura. Swirling sgraffito in the crimson tie adds a controlled vigour to the brushwork.

One’s attention is drawn again to the convincing volume of the face and hands. Yet brushstrokes drift across the void of the background as well as the solid form of the figure, brushstrokes that relate most emphatically to the flat surface on which they are painted, reaffirming the picture plane, collapsing the space that should be afforded the tangible figure.

We are left, finally, with the ambiguities of paint and image, and with the ambivalence of the boundaries between substance and spirit. This painting is a veritable record of the problems confronting a modernist painter who wished to refer both to classic Renaissance masters and also to more contemporary, interior tensions. Dobell has gone beyond representation, and has captured the essence of his friend and model Gabrielides.

Extract from John Hook’s essay ‘Substance and Spirit’ published in Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998.

#QAGOMA