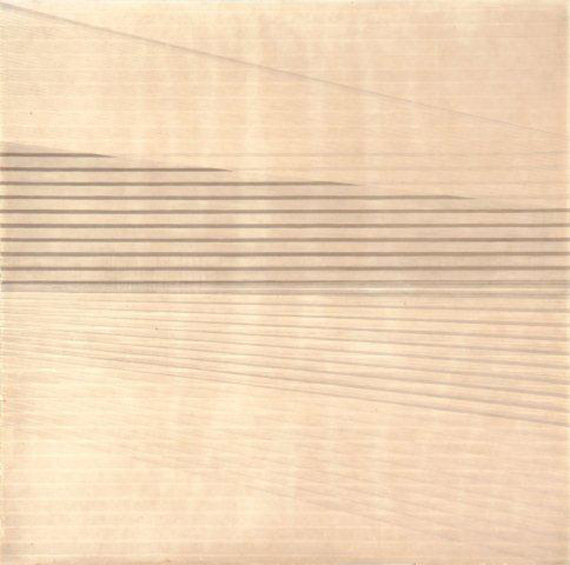

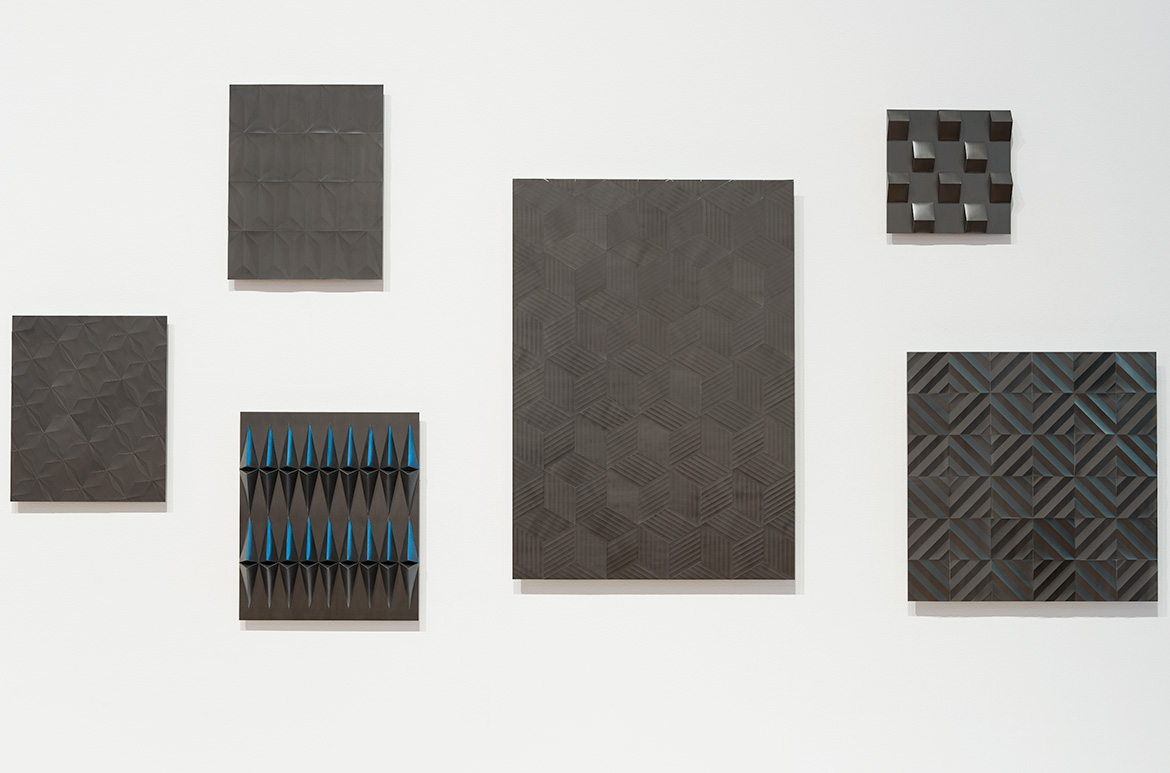

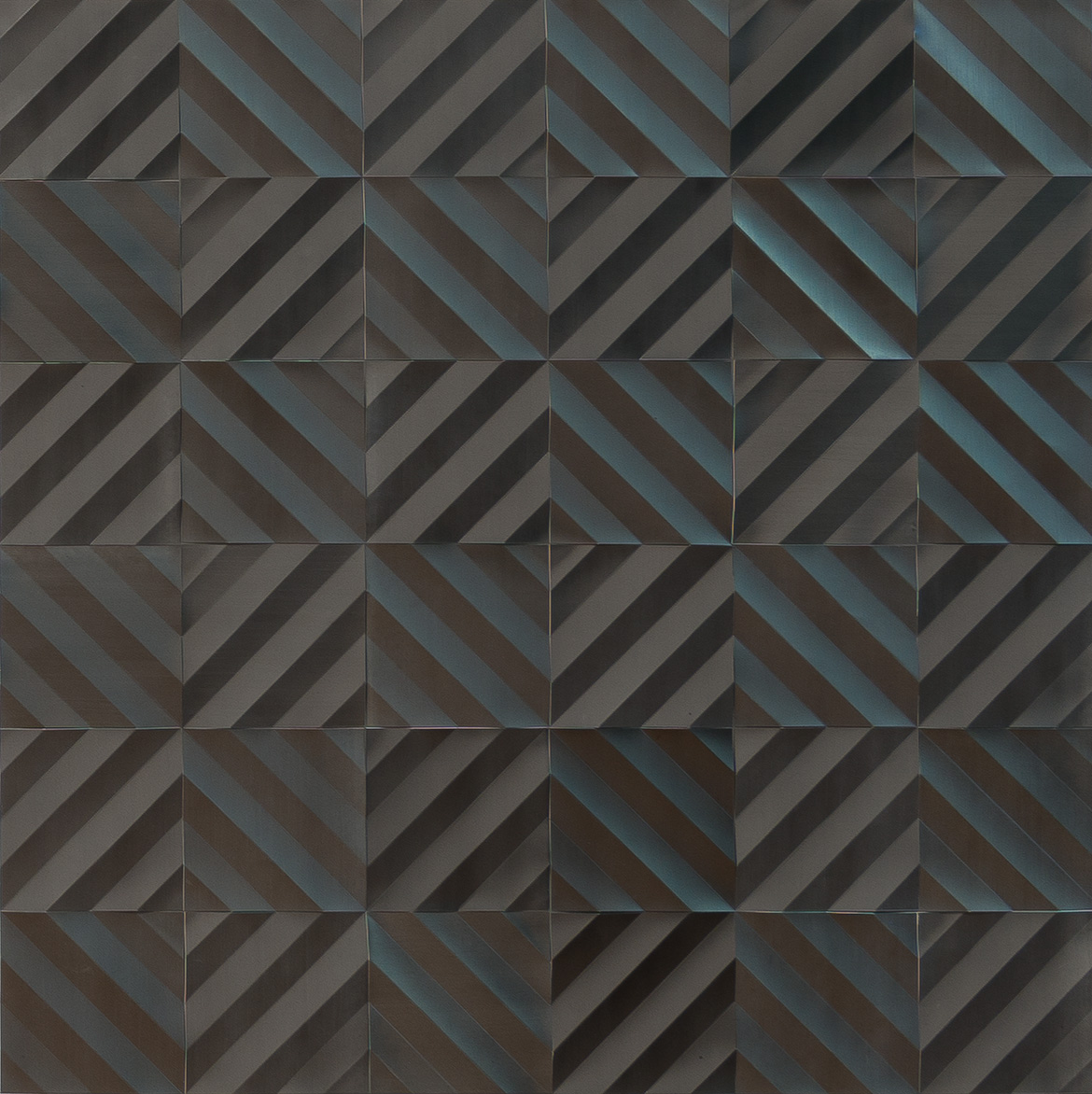

Ayesha Sultana’s graphite works meander between delicate drawings and austere minimalist sculptures. They are created through numerous applications of graphite, using sticks, powder and soft brushes on layers of paper to develop seductive metallic tones. The thickly rendered sheets are carefully cut, folded and fixed into various sculptural compositions, creating rich combinations of shape and depth. At a glance, both the surface and the structure appear streamlined with a burnished, machine-made rigidity, but on closer inspection, a softness and fragility, as well as the natural variation of the hand-drawn, becomes evident throughout the intersecting surfaces.

Although her process is inherently monochromatic and limited to a single material, Sultana finds numerous ways to harness the illusory qualities of her medium in order to explore movement and spatial conversations between the two- and three-dimensional. She uses graphite’s natural reflectivity to produce varying tonal shades in configurations of converging planes, acute repeated shapes, and softly raised surfaces with subtle shifts in tone.

Sultana’s works are abstract and minimal, recalling the rigorous line-work and dexterity of touch of Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–90) and Zarina (Hashmi) (b.1937). Her style, however, developed in a context not normally associated with modern abstract art, and naturally evolved following a period of study in Lahore and then a return to Bangladesh, where she became closely associated with the experimental collective Britto Arts Trust. It was a long process for Sultana to find ways to transform the techniques and knowledge that she had gathered, in order to investigate the abstract qualities of images and her Dhaka environment:

Instead of reading into an image or work of art, I slowly began to discover what ‘looking’ could be. Drawing is useful and concentrated in this manner in that I’m able, to an extent, to assimilate experience by recording myself looking. It was a gradual but deliberate process of discarding the narrative content in the work.1

Sultana’s works are fundamentally about sensory perception. Working in a number of abstracted styles, she translates observation into line, form, depth and texture. Early in the development of her graphite works, she was inspired by the corrugated tinned roofing throughout the city. Similarly, the ‘Untitled (Fragments)’ series of small gouache, ink and graphite works is inspired by the windows and jaalis (lattice windows or screens) of her neighbourhood. Composed of tiny repeated geometric forms, they are experiments in symmetry and uniformity. Other series, including watercolours in monochrome or restrained palettes, are also intimate and delicately scaled, revealing an interplay of geometry or showing a single line softly vanishing through a gradation of spectral colour.

Stay Connected: Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog

While Sultana’s works are not specifically architectural studies, they evoke the built environment and its sensibilities of space, time and memory, bringing to mind Bangladesh’s modernist architecture. The vernacular architecture of Dhaka and the heightened sensory experience of living in the city maintains a particular relevance to her practice, where a glance of the constantly changing streets reveals numerous types of structures in a dense conglomerate of shapes, voids and textures. Sultana attempts to bring these observations into her practice, occasionally working from photographs or with collected objects, and also by considering smells, sounds, objects and materials that are in plain sight, but which are often overlooked.

Ayesha Sultana has developed her own techniques and processes for transforming a multiplicity of sensory experiences into an interplay of space, texture and form. Her approach ensures an abundance of inquiry and possibility, and allows her to develop unique ventures that examine the relationship between materiality, abstraction and observation.

Tarun Nagesh is Curator, Asian Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 Ayesha Sultana, email to the author, 18 May 2018.

Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to be the first to go behind-the-scenes / Watch or Read more about Asia Pacific artists

Buy the APT9 publication

APT9 has been assisted by our Founding Supporter Queensland Government and Principal Partner the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, and the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, State and Territory Governments.

Feature image detail: Ayesha Sultana Vortex 2018

#AyeshaSultana #APT9 #QAGOMA