The Asia Pacific, a region of incredible beauty and diversity, is grappling with the looming challenges of climate change and environmental degradation in the face of economic and political inertia. It is often artists who fire our imagination on these issues, urging us to consider our relationship with the natural world, the ethics of our behaviour and the kind of society we want to leave for the future.

Imagining our relationship with nature

‘Climate change is the moral and political issue of our time,’ writes Max Harris in his book The New Zealand Project, and the importance of this topic is central to the young author’s vision for the future of his country.1 The media offer up daily reports on the catastrophic events that will result from our damaged ecosystem, such as rising sea levels, ocean and river acidification, desertification, extreme weather events and species extinction. As I write this, an article in The Economist confirms that the world is in a ‘war’ with climate change and losing — partly due to our demands for energy, and partly due to economic and political inertia2 — and our national government backs further away from the Paris Accord.

According to Harris, however, artists are firing our imagination in an effort to counter climate change listlessness.3 Art plays an important role, not only in raising consciousness of carbon and climate challenges, but also in urging us to actively rethink our relationship with the environment. Art has power: some authors contend that it is more likely to stimulate public debate regarding anthropogenic climate change — and involve a broader constituency of people in such a debate — than the restating of scientific facts or appeals to ‘common sense’.4

A number of APT9 artists convey their attitude towards the natural world in works that intelligently and productively encourage us to place a greater value on the ecosystem of which we are a part.

Stay Connected: Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog

‘If we die, we’re taking you with us,’ says a bee in Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner’s poem ‘The Butterfly Thief’.5 Originally from the Marshall Islands but now based in Oregon in the United States, Jetñil-Kijiner is a climate change activist, poet and performance artist whose voice demands to be listened to. Her poems have been published and recognised internationally, including at the opening of the United Nations Climate Summit in 2014, where her presentation focused on saving humanity by taking responsibility for the effects of climate change.6

For APT9, Jetñil-Kijiner instigated the Jaki-ed Project by Marshall Island weavers, which encourages youth and Pacific communities to maintain their local weaving traditions. However, she is better known for her poetry and spoken-word performances that call for ways to halt climate change and the devasting impact it is having on the Marshall Islands and other island nations. Like Harris, she recognises the catastrophic effect that damaged ecosystems are having on all humanity and the need for collective global action. In particular, she advocates for Pacific cultures to not merely survive but to thrive through shared values and collaborative action.

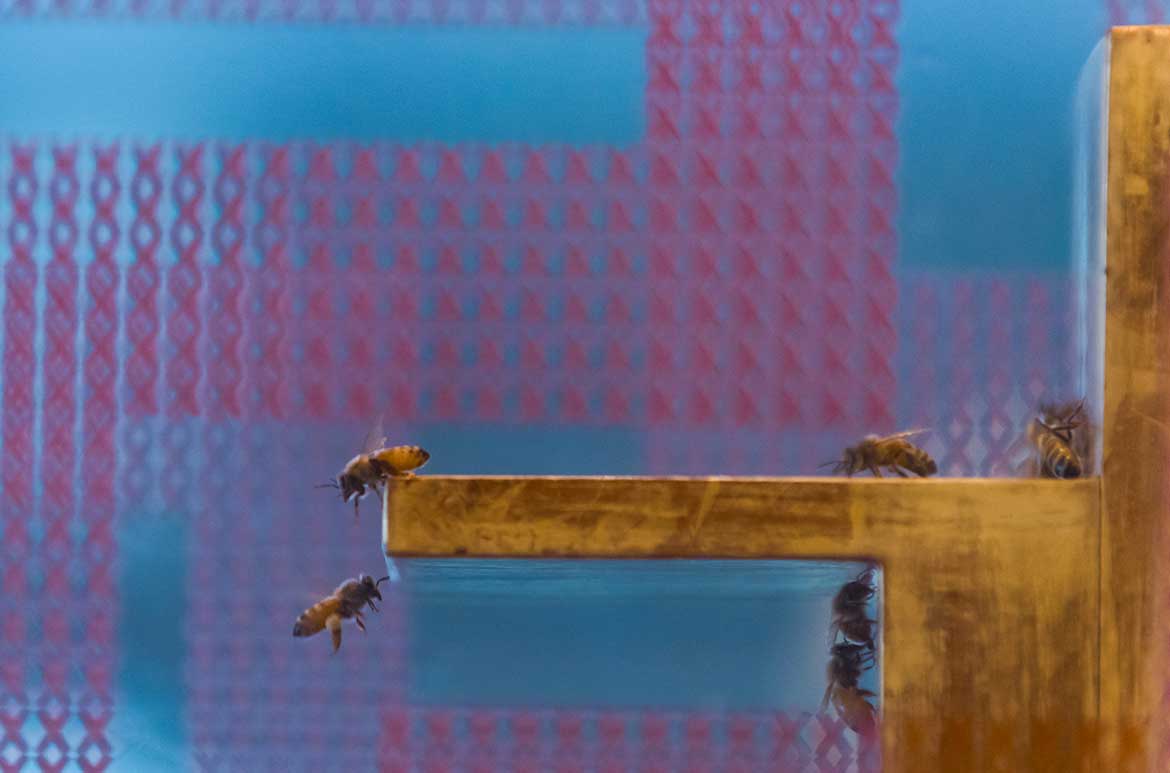

Anne Noble is another artist exploring the critical role of bees in a functioning ecosystem. The wellbeing of the honey bee is a measure of environmental health, but these insects are due to lose half their habitat under current climate predictions, leading scientists to warn of an ‘ecological Armageddon’.7 Bees are essential to botanical life as pollinators of plants, but their existence as a species is threatened by chemicals introduced in the genetic engineering of agriculture.

Noble’s project in APT9 celebrates the world of this insect but symbolises the real threat of its demise. Her video work Reverie 2016 and her installation ‘Museum: For a time when the bee no longer exists’ offer viewers an opportunity to experience the dreamlike atmosphere of a hive in summer. Noble aims to stimulate dialogue about the significance of the bee to our lives and to build awareness of our inherent relationship with and responsibility to the bee as part of a shared existence. To these ends, APT9 includes a living beehive within Conversatio: A cabinet of wonder 2018, from where bees go about their communal roles, collecting pollen outdoors to bring into the gallery.

To understand the factors influencing the honey bee’s decline, Noble became a beekeeper and has subsequently worked with communities, schools, scientists and professional and amateur apiarists to engage people of all ages with the lives of bees. She has also drawn on the work of nineteenth-and early twentieth century biologists and writers such as Goethe or Rudolf Steiner, whose study of nature fuses science with a poetic and philosophical register. Noble says that she is ‘working to create a series of frames through which to engage audiences with new narratives and meanings more appropriate to the current and future challenges facing the world’s ecosystem and our role in its rapid transformation’.8 Her work abounds with wonder, joy, emotion and curiosity, enticing her audience to learn more about the bee and the insect world.

Among other APT9 artists whose work is inspired by the natural world, several share the common theme of humanity as an integral part of the Earth’s ecosystem, including Singapore’s Donna Ong and Robert Zhao Renhui, Malaysian collective Pangrok Sulap, and Martha Atienza and Nona Garcia, who both work in the Philippines.

The collaborative installation by Ong and Zhao, My forest is not your garden 2015–18, offers the wonder of a museum diorama in the Queensland Art Gallery Watermall. Ong’s evocative arrangements of artificial flora and tropical exotica blend with Zhao’s archival-style display of a collection of authentic and fabricated objects that purportedly relate to Singapore’s natural history.9 Ong takes a critical perspective on how representations of the tropics in science, botany, art, illustration and gardens have influenced human relations with nature. Zhao performs his speculative scientific investigations of relations between humans and animals through the creative framework of the ‘Institute of Critical Zoologists’, playing with forms of knowledge such as the zoological gaze and natural history research projects.10 These artists encourage us to understand that the lens through which we see the natural world has simultaneously reshaped it.

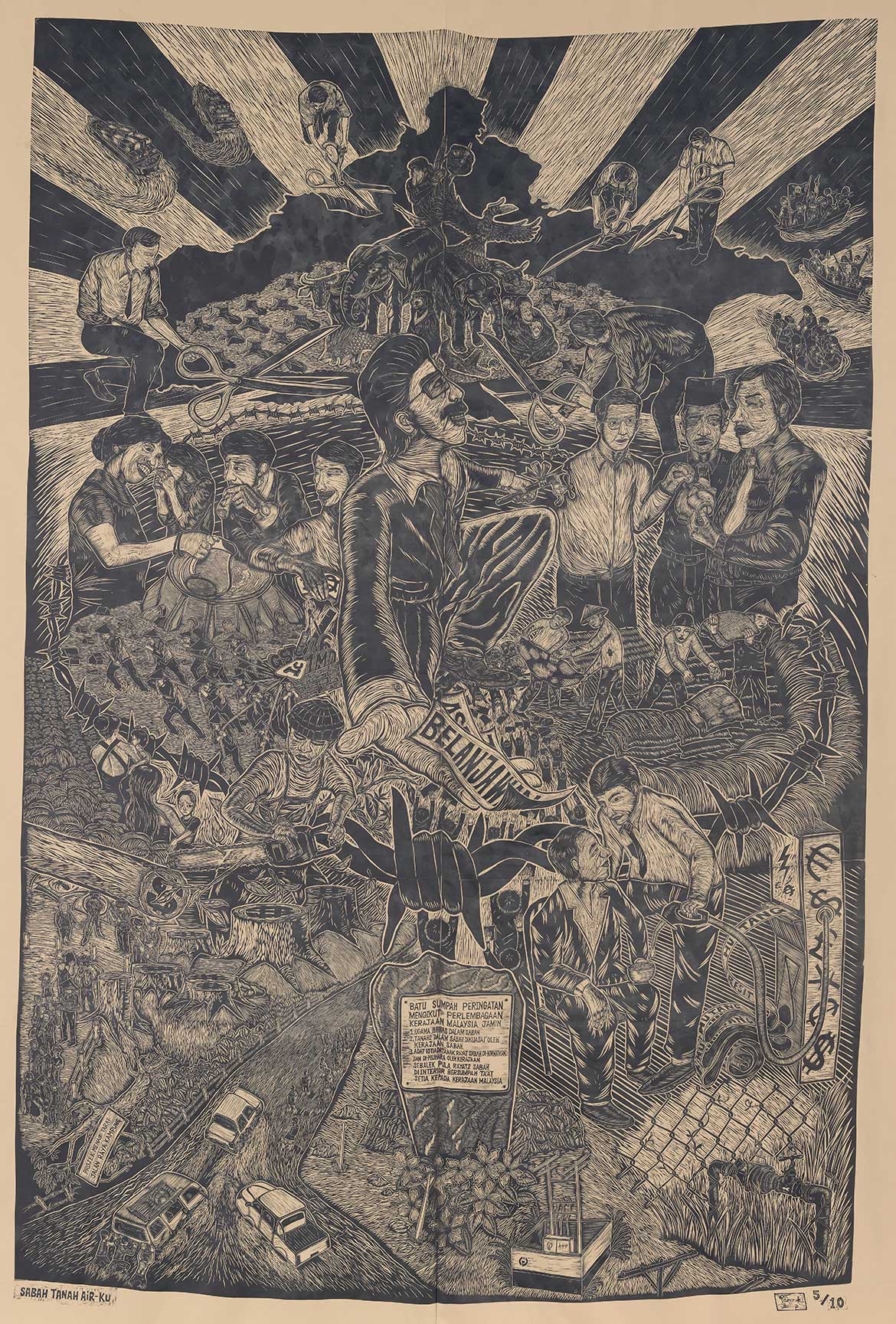

Based in the East Malaysian state of Sabah in northern Borneo, Pangrok Sulap is a collective of artists, musicians and social activists who collaborate with the community to bring attention to local issues. Their largescale two-part graphic woodcut, Sabah tanah air-ku 2017 — which translates to ‘Sabah, my homeland’, the name of the state’s official anthem — maps in intricate detail both the bounty and exploitation of their environment. One panel features the iconic Mount Kinabalu accompanied by the anthem’s final line, ‘Sabah Negeri Merdeka’ (‘Sabah independent state’), expressing the people’s dream of autonomy. The second panel represents the darker reality of corruption, the extraction of profit from the local community by mining and other industries, and mistreatment of the land and people by both national and international interests. These artists clearly show the contemporary issues we face when the natural world is considered a cost-free resource available to exploit.

Watch as Martha Atienza discusses her video projects

The despoliation of land in Sabah, which ruins subsistence lifestyles, is similarly an issue raised by Martha Atienza in regard to her father’s home region of Bantayan Island in Cebu, the Philippines. Atienza’s underwater video Our Islands 11º16’58.4 N 123º45’07.0 2017 recreates an Ati-Atihan procession (part of the annual Filipino festival devoted to the child Jesus) with her protagonists breathing through the compression diving equipment used by locals, who are forced to seek fish at progressively greater depths. Atienza uses video as a tool to unify the local people and provoke discussion about the future. ‘The ocean is so damaged — there’s no livelihood, and our culture is disappearing,’ she says. ‘I really hope that people can use this video to have a dialogue, and I really hope that by sharing it, people can go home and have conversations about it.’11

Back on land, Nona Garcia’s suite of paintings, Untitled pine tree 2018, records one of the giant aged specimens that have been destroyed over the past decade in Baguio City — more than 600 kilometres north of Bantayan — to make way for development, generating large community protests and the slogans ‘Cut your greed, not our trees’ and ‘The land is meaningless without trees’.

In heightening our awareness about environmental challenges, Harris discusses how indigenous cultures — such as Te Ao Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand — often speak of being intertwined with the environment; humans are not at the centre of the natural world but are dependent on and exceeded by it.12 APT9 artist Kapulani Landgraf incorporates such a view in her art, which she considers is a vehicle for raising awareness of injustice. Landgraf is a Kanaka Māoli, a native Hawaiian, whose images express the toll of development on her people and land. Her stark, large‑format photography and photographic collages detail the destruction of the environment through urban development, militarisation and the increasing commodification of life post colonisation. Following the tradition of photomontage as a political weapon, Landgraf’s works both challenge the viewer and assert the resilience of her people by considering indigenous and ancestral ways of knowing and understanding the land.

Each of these artists follows Harris in understanding the centrality of nature to how we thrive and survive. They engage deeply with environmental politics and offer different perspectives on the world we live in. Our relationship with the natural world is part of the broader question about the kind of society we want, a subject that belongs in a larger conversation regarding the economic or scientific control over ecological issues, which is often couched in the language of resource management.

These artists’ works in APT9 ask us to consider the shared custodianship and responsibility for our planet’s ecosystem as positive social values.

Dr Zara Stanhope is Curatorial Manager, Asian and Pacific Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Max Harris, The New Zealand Project, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2017, p.202.

2 ‘In the Line of Fire’, The Economist, 4 August 2018, p.7.

3 Harris, p.214.

4 Tom Crompton, Common Cause: The Case for Working with our Cultural Values, WWF UK 2010, p.19, <https://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/common_cause_report.pdf>, viewed August 2018. Anthropocene is the name proposed for a new geological epoch defined by human impact on Earth. However, scientists remain wary of attributing human impact rather than drought on the geological definition of our current epoch. See Graham Lloyd, ‘Paper gets scientists hot under the collar’, The Weekend Australian, 11 August 2018, p.16.

5 Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, ‘“Butterfly Thief” and the complex narratives of disappearing islands’, <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/butterfly-thief-and-complex-narratives-of-disappearing-islands/>, viewed August 2018.

6 Statement and poem by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, Climate Change Summit 2014 Opening Ceremony, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mc_IgE7TBSY>, viewed August 2018.

7 Damian Carrington, ‘Climate change on track to cause major insect wipeout, scientists warn’, The Guardian, 18 May 2018.

8 Anne Noble, artist statement [unpublished] for Song Sting Swarm 2012.

9 This collaborative installation comprises Donna Ong’s From the tropics with love 2016 and Robert Zhao Renhui’s The Nature Museum 2017.

10 Robert Zhao Renhui’s Christmas Island, Naturally 2015–16, a speculation on removing all species from the island, was seen in the 2016 Sydney Biennale.

11 Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta, ‘Marta Atienza prize-winning “Our Islands” comes home’, ABS-CBN News, <http://news.abs-cbn.com/life/02/28/18/martha-atienzas-prize-winning-our-islandscomes-home>, viewed August 2018.

12 Harris, p.216.

Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to be the first to go behind-the-scenes / Watch or Read more about Asia Pacific artists

APT9 publication

APT9 has been assisted by our Founding Supporter Queensland Government and Principal Partner the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, and the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, State and Territory Governments.

Anne Noble has been supported by Creative New Zealand.

Martha Atienza has been supported by the Australian-ASEAN Council.

Feature image detail: Anne Noble’s Dead Bee Portrait #2 2015–16 / Courtesy: The artist and Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland / © Anne Noble.

#APT9 #QAGOMA