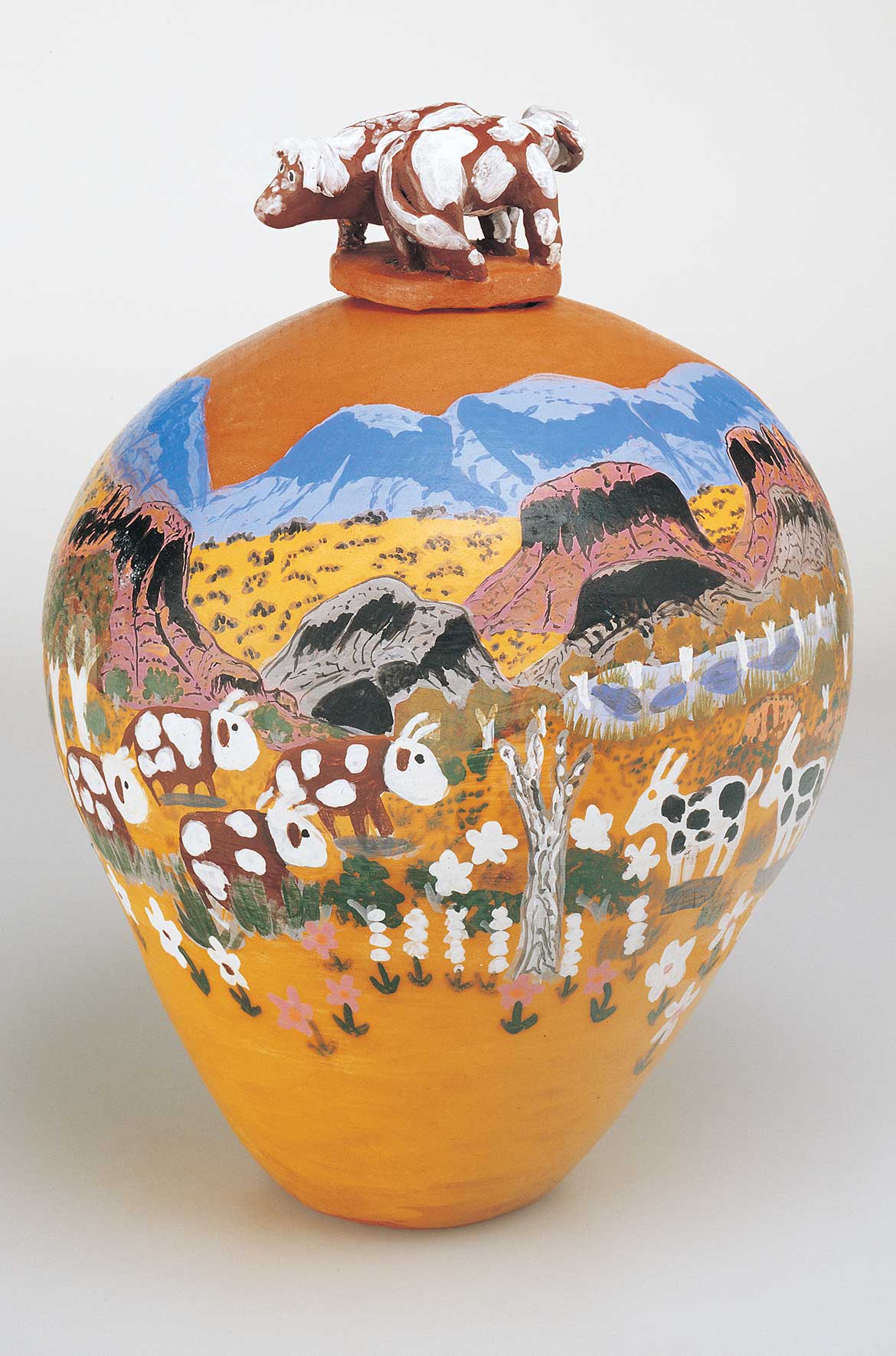

Three painted terracotta pots by Arrernte–Luritja artist Irene Entata depict three distinct periods in Arrernte artist Albert Namatjira’s life, including the sad circumstances of his death.

One of the foremost artists of the Hermannsburg Potters, Irene Entata (1946–2014), is known internationally for her unique painted ceramics. Much of her art fondly depicts a time that she referred to as the ‘Mission Days’, when the Central Desert community of Hermannsburg — situated among the rolling hills of the MacDonnell Ranges, west of Alice Springs — was run by the Lutheran mission during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Entata’s pots often show the white buildings of the missionary precinct, such as the Strehlow house (owned by the German anthropologist and linguist Carl Strehlow) and the old school and church. Although many recall the strictness and cruelty of the missionaries, some older Aboriginal Christians, including Entata, saw the mission as providing structure and purpose to the lives of local people and giving greater social cohesion to the wider community.

Among the most important works Entata produced were her pots and paintings of Albert Namatjira, revealing an Arrernte perspective on the revered Australian artist. As a girl, Entata remembered seeing Namatjira painting with his sons, along with the Pareroultja brothers (Otto, Reuben and Edwin) and Richard Moketarinja.1 After attending the Hermannsburg school, where she drew and did some plasticine modelling, Entata became a health worker and cleaner before making her first pots at Tjamankura with her sister, Virginia Rontji, in 1990. The three works featured here, made a decade into her practice as a ceramist, chronicle distinct periods in Albert Namatjira’s life, including the sad circumstances of his death.

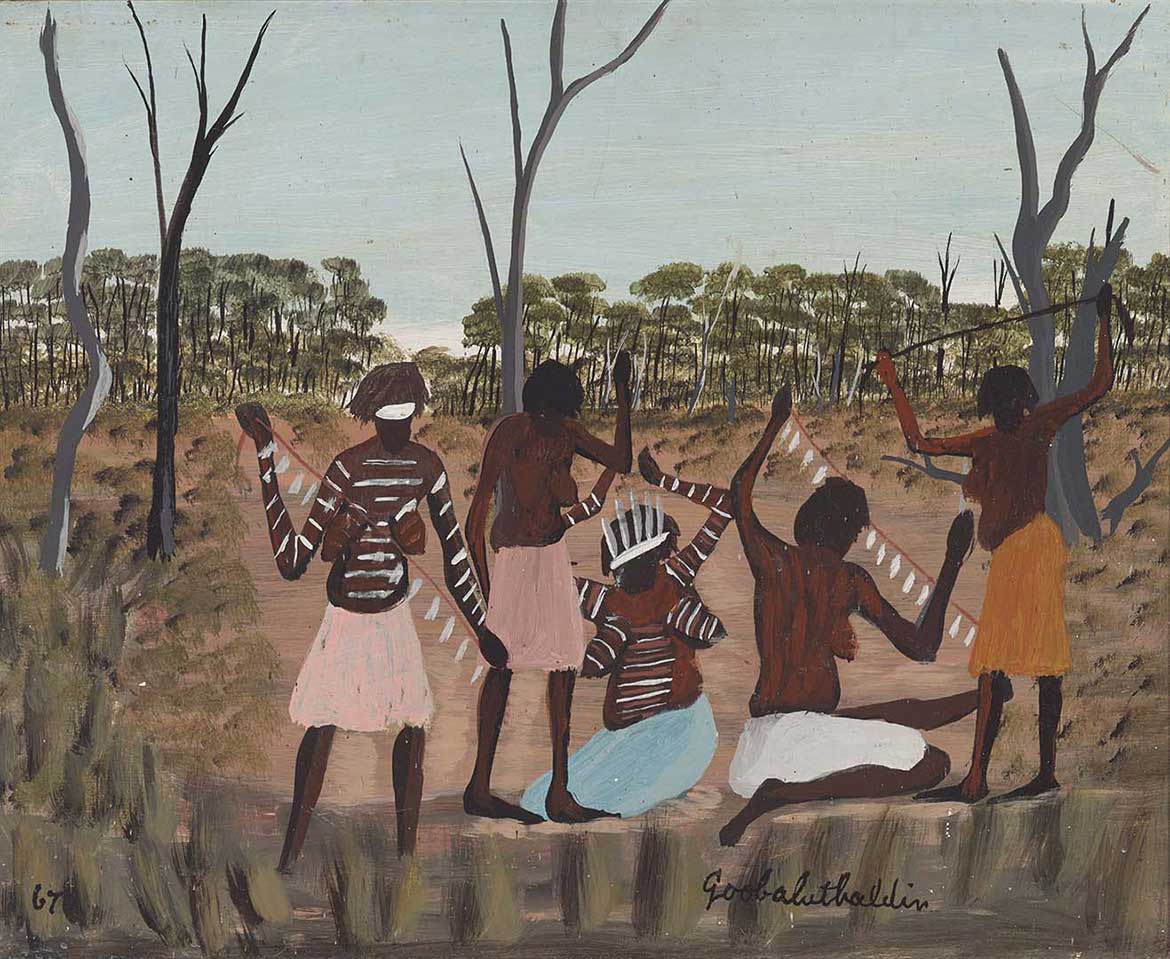

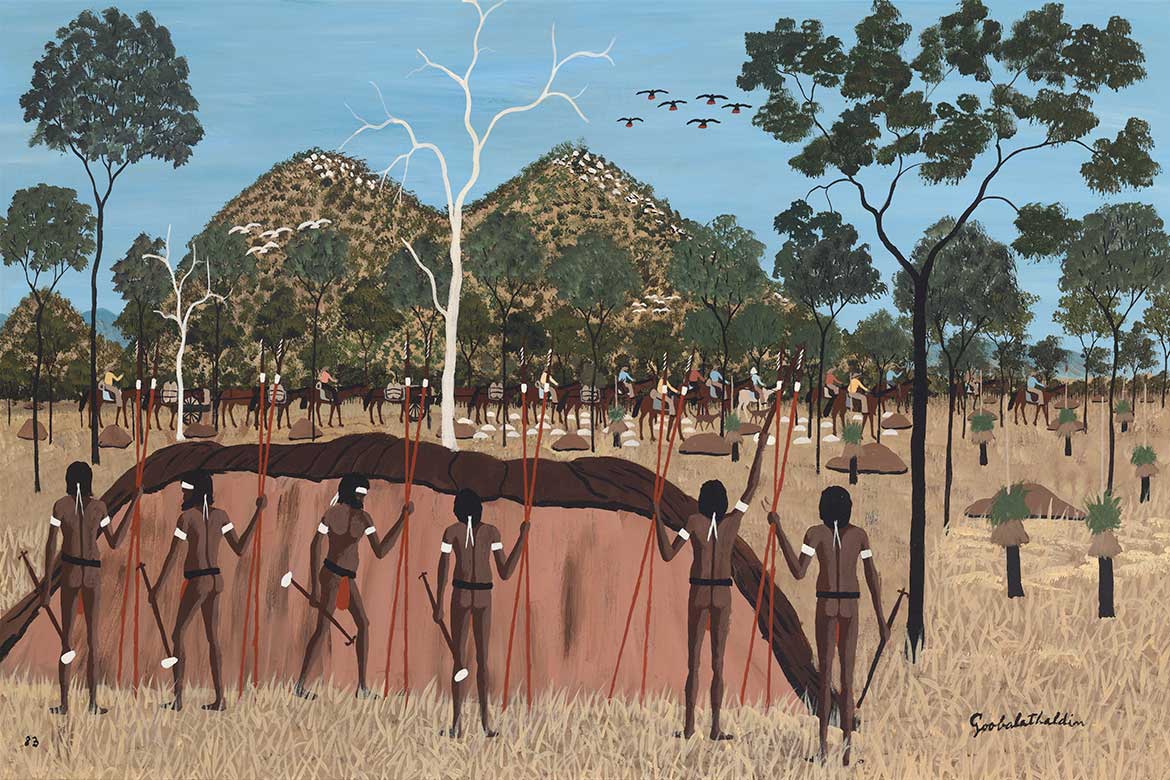

Albert Namatjira droving

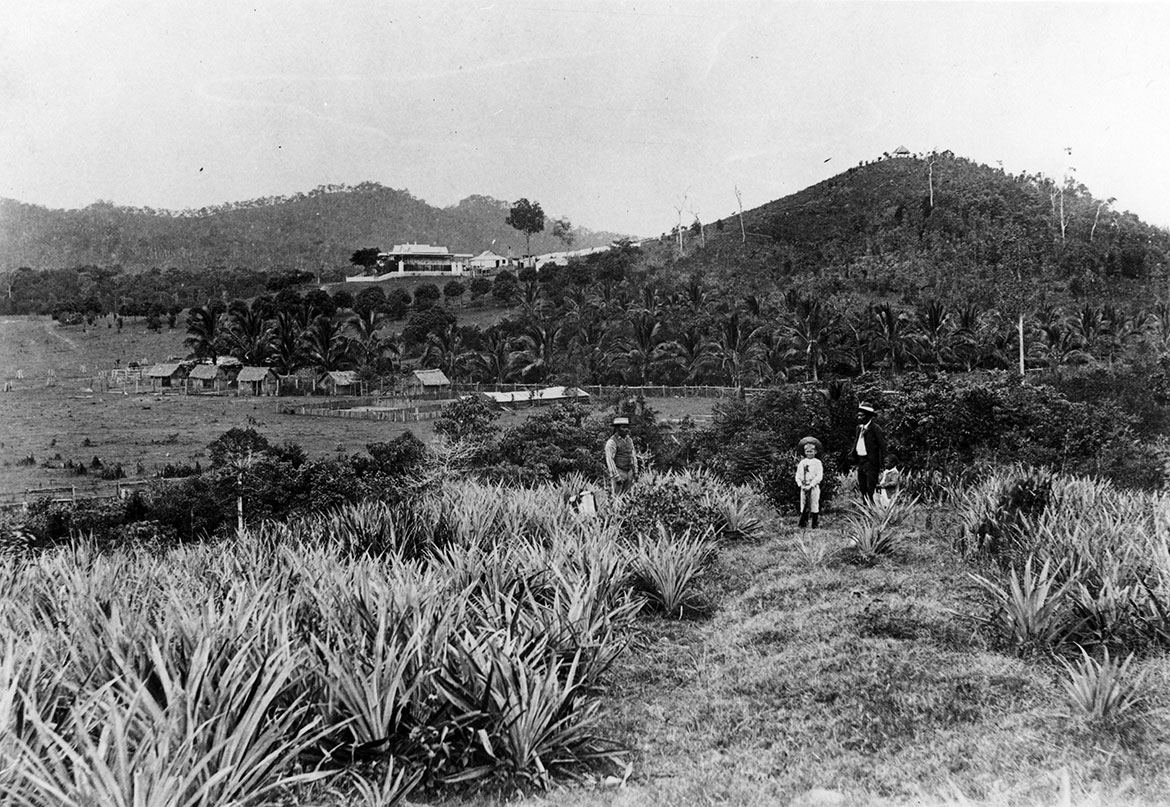

Albert Namatjira droving 2001 depicts a young Albert droving cattle around Gilbert Spring, a water site at the base of the Krichauff Ranges, west of Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and south of Tnorala (Gosses Bluff), where wildflowers grow abundantly in season and food is in good supply for cattle. Across Australia, many Aboriginal men were heavily involved in the cattle industry. Boys were frequently sent out to work as drovers and stock hands from the age of 14, and their droving skills became a source of pride as they reached adulthood. Here, Entata shows Albert among the other Aboriginal men droving cattle and sitting yarning atop cattle yard fences, surrounded by their Arrernte country in bloom.

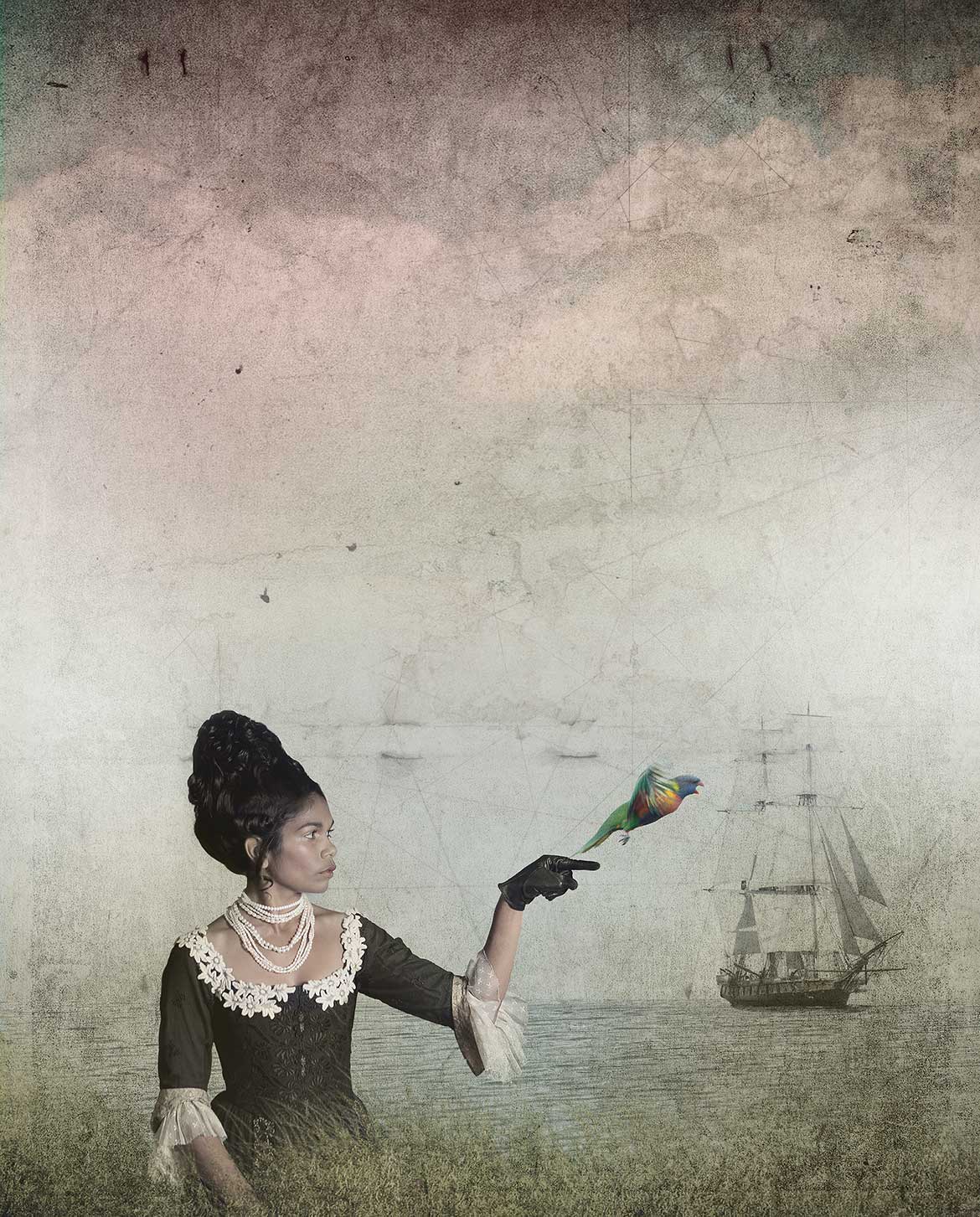

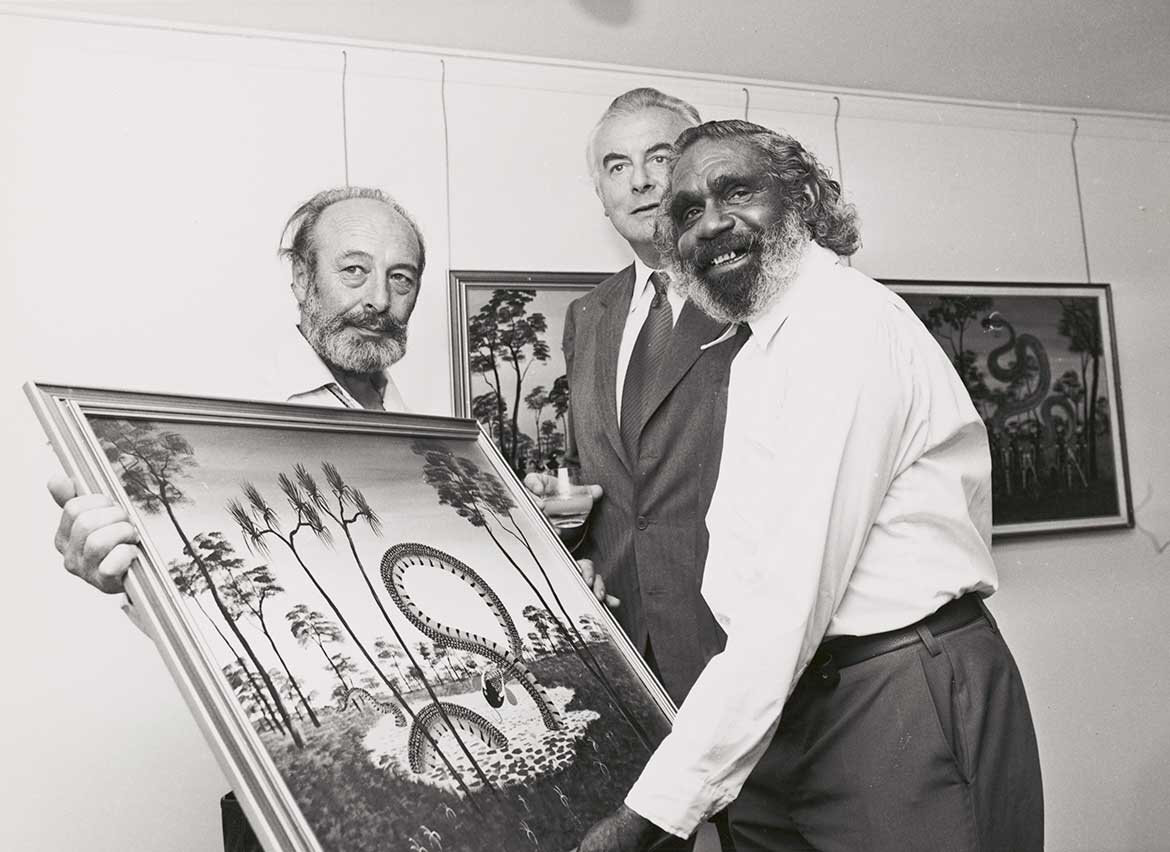

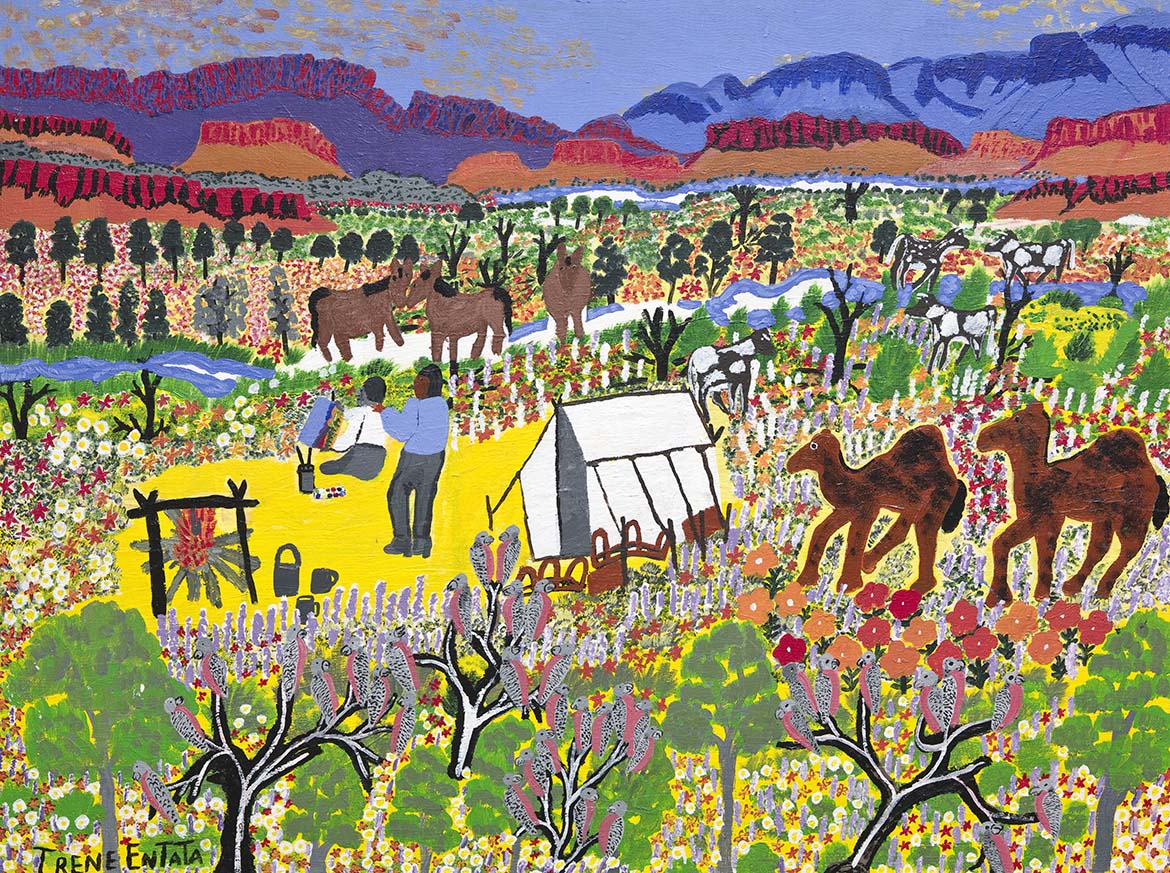

Rex and Albert painting in Palm Valley

Rex and Albert painting in Palm Valley 2001 features Albert painting alongside his mentor, Rex Battarbee, at Palm Valley, nestled within the ranges behind Mount Hermannsburg. This scene imagines the beginning of the Arrernte art movements from Ntaria, when Albert accompanied Battarbee on a painting expedition through the Western MacDonnell Ranges. Albert exchanged his skills as a cameleer and guide for painting lessons from Battarbee, and from this six-week expedition followed a lifelong friendship. They shared a single tent and used camels to transport their swags and painting materials. The composition of the painting on this pot is strikingly similar to another work in the Collection by Entata, titled Albert and Rex painting 2003, in which a seated Albert paints the ranges as Battarbee stands behind, pointing out elements of the landscape.

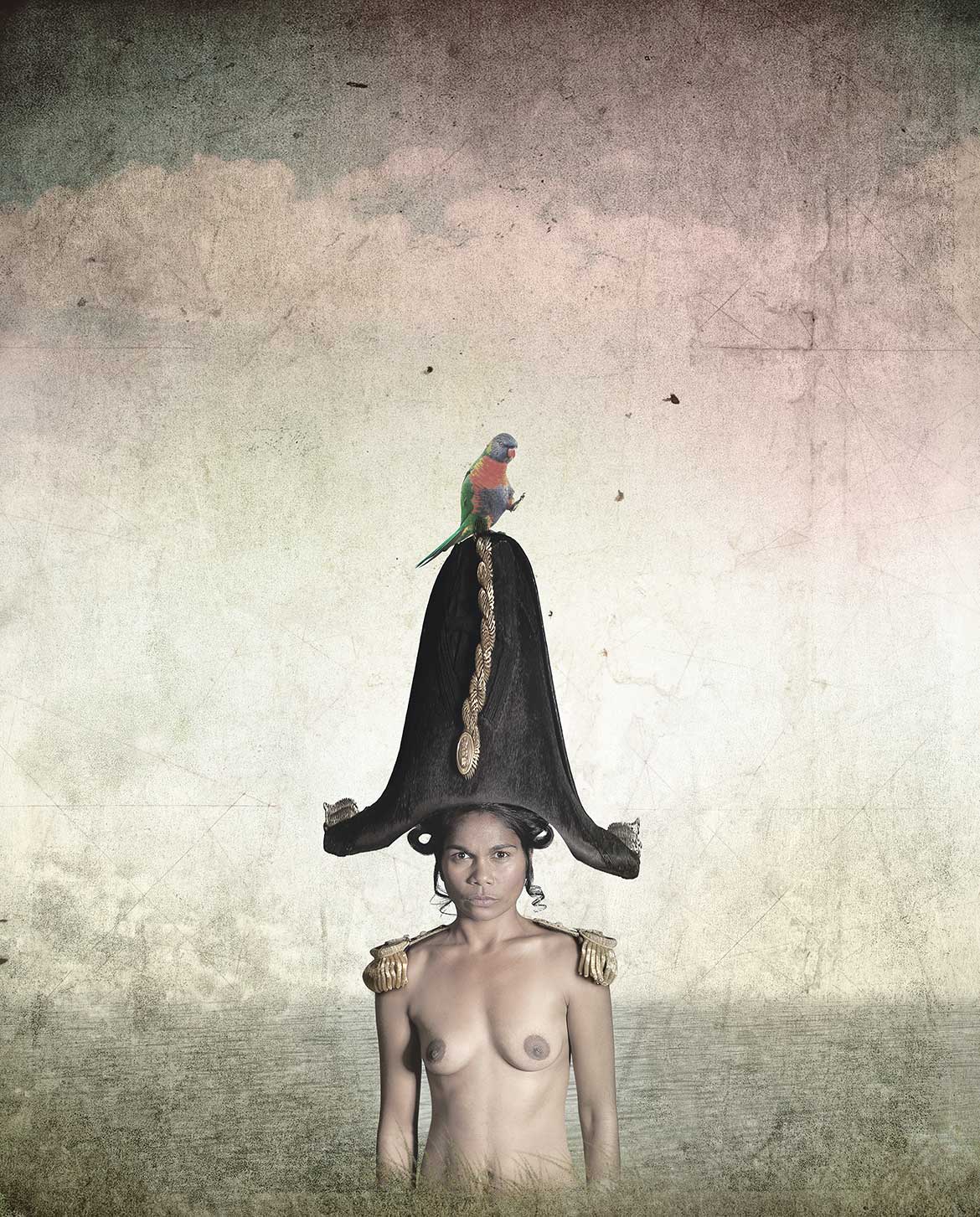

The events leading to Albert’s death

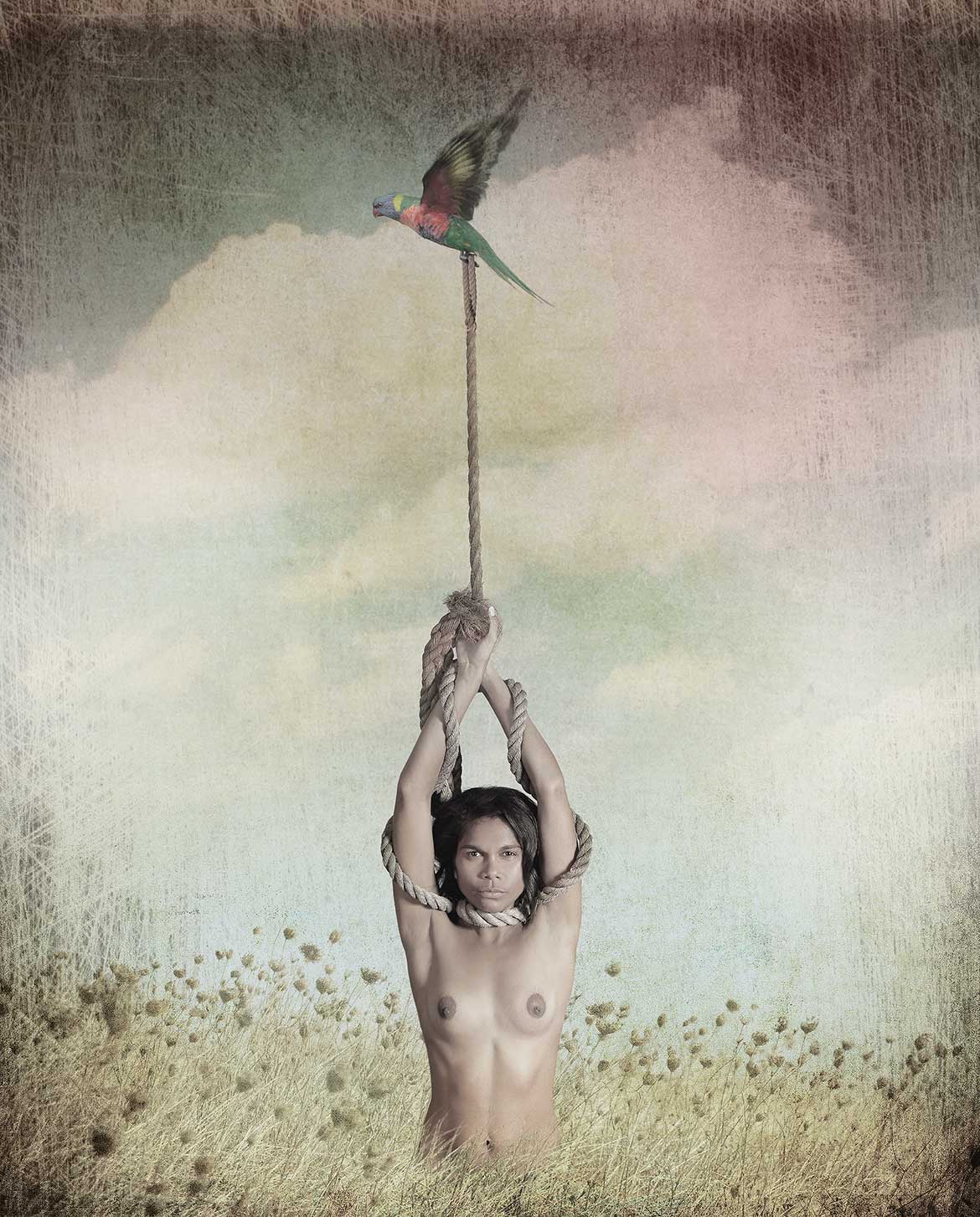

The events leading to Albert’s death 2001 recounts the tragic final pieces of Albert Namatjira’s life story. Although he became the first Aboriginal person to be granted Australian citizenship in 1957, enabling him to move to Alice Springs and seek better access to services and economic markets, he faced continued discrimination. Despite being one of the country’s most renowned artists, he spent his later years living in poverty. Prevented from buying a house, he lived with members of his extended family in corrugated iron shanties in the creek bed at Morris Soak. As a citizen, he could purchase alcohol; without a house, however, he had nowhere to store it, making it accessible to family members for whom drinking was prohibited. One night, fellow artist Henoch Raberaba took a bottle of rum from Albert’s car and killed a young woman in a drunken rage. Convicted of supplying alcohol to Aboriginal people, Albert was jailed at Papunya for three months. He suffered a heart attack shortly after his release and passed away in hospital in Alice Springs a few days later.

Irene Entata’s pot captures this story with an image of Albert sitting in the creek bed drinking alcohol surrounded by family members. On the opposite side he is incarcerated behind bars, and the lid features a moulded replica of his headstone, made by members of the Hermannsburg Potters in 1994. Following a renewed interest in Albert’s life and work during the early 1990s, the Potters renovated his previously nondescript grave: now, a large slab of white stone from his country is inlaid with a landscape painted onto ceramic tiles, inspired by one of his paintings of the Western MacDonnell Ranges. His granddaughter, Elaine Kngwarria Namatjira, led the project, with assistance from Elizabeth Jane Moketarinja and Kay Panangka Tucker, ensuring their important Elder had a fitting memorial.

Bruce Johnson McLean is former Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA.

Endnote

1 Artist’s statement in Jennifer Isaacs, Hermannsburg Potters: Aranda Artists of Central Australia, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2000, p.100.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Irene Entata Rex and Albert painting in Palm Valley 2001

#QAGOMA