The recent passing of Inge King AM, and Bea Maddock AM saw the loss of two significant and highly respected figures in Australian art. We commemorate these great women in the Collection.

Inge King

Ingeborg Viktoria (Inge) King AM (1915–2016) was a leading non-figurative sculptor in Australia for more than five decades. Born in Berlin, she moved to Australia in 1951 and was a founding member of Centre Five, an important Melbourne group of modern sculptors who were strong advocates of contemporary sculpture in the public realm. King exhibited regularly from the 1960s, as well as producing many significant public sculptures. She was also a long-time member of the Gallery’s Foundation.

Inge King’s Sculptural form 1958 (Illistrated), which she generously gifted to the Collection in 2015, is a primary example of the organic nature of her early work and her forays into carving and casting. Following her move to Australia, King’s work changed markedly from earlier emotive figurative abstractions in wood and stone. Sasha Grishin characterised this period as one of:

. . . gestation during which she acquired new skills, experimented with new materials and was struggling to come to grips with the Australian landscape and cultural environment and her own position as a migrant woman artist with two small children.1

In 1959, King began making welded sculptures, originally working the metal to make rugged expressive forms. Gradually, however, she both simplified and reduced them in form, but even the smallest of her sculptural objects possess a simultaneous intimacy and monumentality, a counterpoint to the imposing monumental style for which she is best known. King’s celestial Great planet 1976–77 (Illustrated) is a monument in steel, painted black, with a circular void at its centre. Sculpture writer Ken Scarlett observed that: ‘beyond its formally satisfying design, Great planet has an air of mystery, an aura of power and a commanding presence’.2

King’s interest in suspended sculptures was first exemplified by her Calder-influenced works of the early 1950s; Hanging sculpture, 3rd version 2002 returns to this preoccupation. Around 2000, her work turned to a long series of figurative abstractions, based on dynamic bodies in motion, mythical beings, birds and animals, of which this gift of the artist to the Collection is an example.

Bea Maddock

Beatrice Louise (Bea) Maddock (1934–2016) was born in Tasmania, and after training in Hobart in the mid 1950s, she left for London in 1959 to undertake postgraduate studies in painting and printmaking at the Slade School of Art, travelling to France, Italy, Holland and Germany during vacations. She returned to Australia in 1962, basing herself first in Launceston and Melbourne.3 She exhibited widely in Australia and overseas, and was a dedicated senior educator who moved in and out of teaching throughout her career.

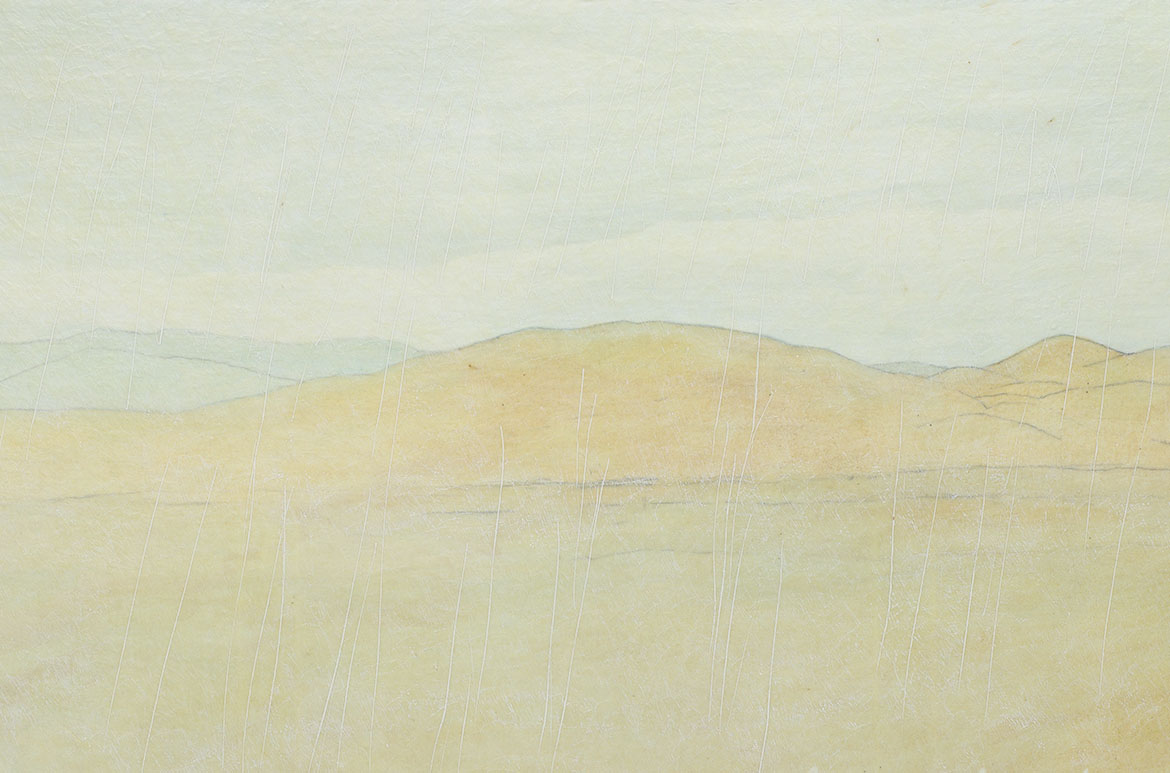

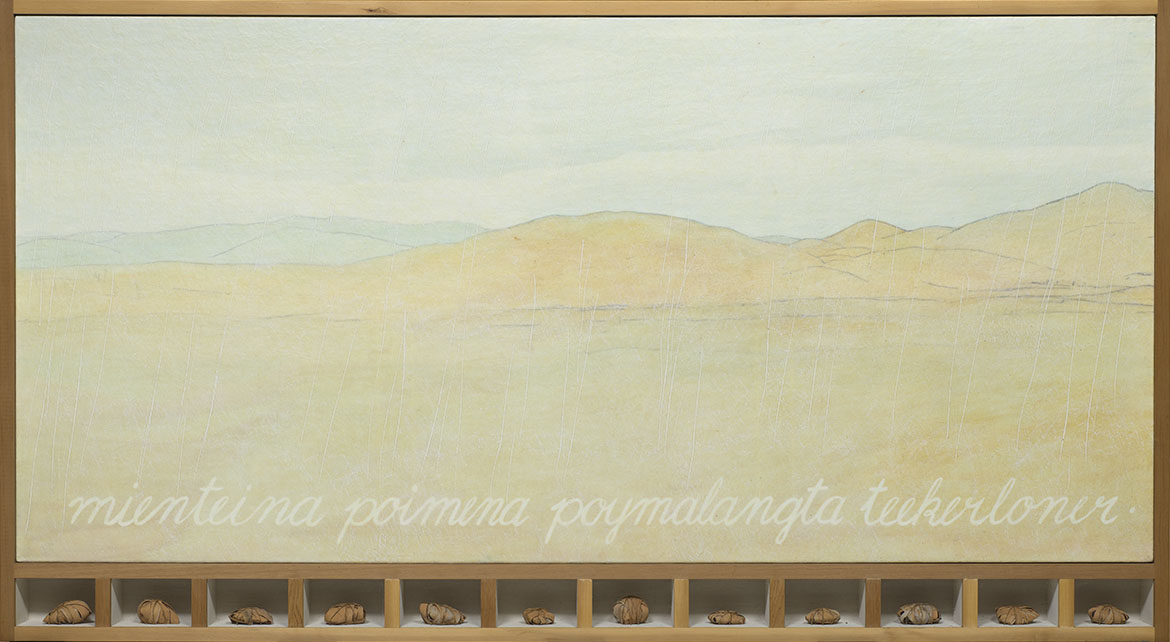

Maddock worked with technical prowess across many media including drawing, photography and painting, though she is best known for her printmaking and artist books. Her oeuvre has gravitas, autobiographical introspection and a sense of quietude — isolation, loneliness and colonised histories were common themes. She explored the history of her home state of Tasmania, and the effects of colonisation, in two major works in the Collection. Maddock’s multi-panelled encaustic (wax and pigment) and collage landscape work Tromemanner – forgive us our trespass I–IV 1988–89 (Illustrated) is a panoramic landscape with geographic texts in English and Aboriginal languages. Produced for ‘The Jack Manton Exhibition 1989: Recent Work by Twelve Australian Artists’, Tromemanner depicts the Saltpan Plains at Tunbridge and addresses the devastating colonial history of the island. Beneath the landscape and texts, Maddock included a series of artifacts in individual compartments. In 1992, curator Anne Kirker wrote:

there are 48 artifacts in all, representing the approximate numbers of bands (sub tribal groups) belonging to Tasmania . . . By choosing this Australian state as her focus, she not only asserts a personal identity with it, but faces up to the historical facts of the genocide of the original inhabitants of Van Diemen’s Land.4

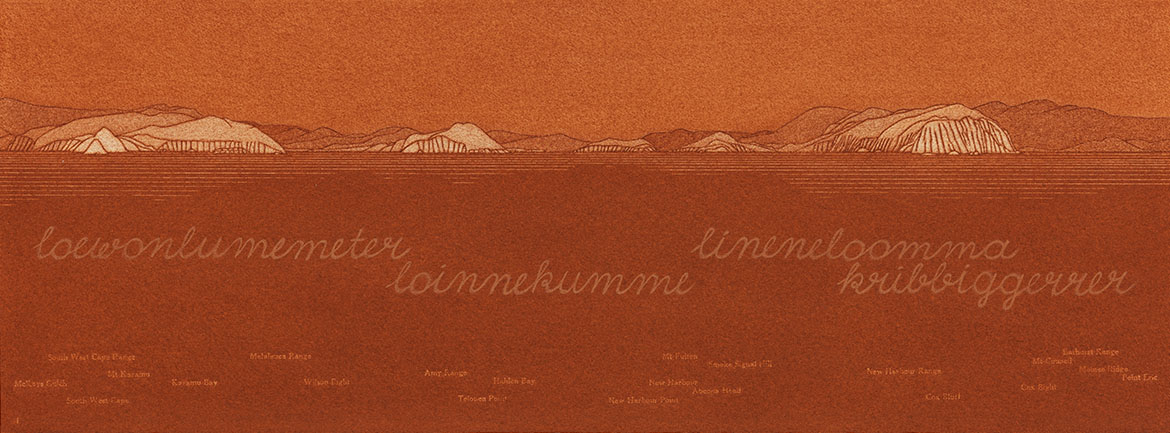

Maddock followed Tromemanner with TERRA SPIRITUS … with a darker shade of pale (Illustrated) 1993–98 — a 40-metre panorama in ochre, which Maddock gathered and ground by hand — a work that documents and meditates on the entire coast of Tasmania. The geography depicted across the drawing’s 50 sheets is again named by the artist in both English and Aboriginal languages, recorded respectively in letterpress and hand-drawn script across the ocean. Technically astute, the work combines aspects of drawing and printmaking through a stencil process, and takes viewers on a journey of circumnavigation, rewarding both the long view and close inspection.

The recent passing of these significant and highly respected figures is a major loss for Australian art, and we feel privileged to have the works of such great Australian women artists in the Collection.

Endnotes

1 Sasha Grishin, The Art of Inge King: Sculptor, Australian Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2014, p.76.

2 Ken Scarlett, ‘Centre Five Revisited’, in Lynne Seer and Julie Ewington, eds. Brought to Light II: Contemporary Australian Art 1966–2006 from the Queensland Art Gallery Collection, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2007, p.20.

3 Anne Kirker, ‘Bea Maddock’, in Janet Hogan (ed.), The Jack Manton Exhibition 1989: Recent Work by Twelve Australian Artists [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, 1989, pp.16-17.

4 See Anne Kirker and Roger Butler, Being and Nothingness: Bea Maddock [exhibition catalogue], Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1992, pp.13–22.

Kyla McFarlane is former Acting Curatorial Manager, Australian Art, QAGOMA

#QAGOMA